- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Counter-Insurgency in Rhodesia (RLE: Terrorism and Insurgency)

About this book

When originally published in 1985 this volume was the first scholarly and objective contribution available on Rhodesian counter-insurgency. It documents and explains why Rhodesia lost the war. The origins of the conflict are reviewed; each chapter examines a separate institution or counter-insurgency strategy directly related to the development of the conflict, concluding with a summary view of the Rhodesian security situation both past and present.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Counter-Insurgency in Rhodesia (RLE: Terrorism and Insurgency) by Jakkie Cilliers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WAR FOR ZIMBABWE 1965–1979

1.1 The Early Years

By 1890 there were already a number of white settlers inhabiting what was later known as the British colony of Southern Rhodesia. The impingement of white interests upon indigenous black customs and property, however, led to racial tension. So, in 1893 and again in 1895, the Matabele regiments rose up under their king, Lobengula, in the first freedom struggles or Chimurenga against the whites. Although the black warriors were overwhelmingly defeated this did not secure the position of the white settlers, who remained ill at ease in their isolated outposts across Mashonaland. White military preparedness was consequently directed towards securing internal security and remained so for a number of years.

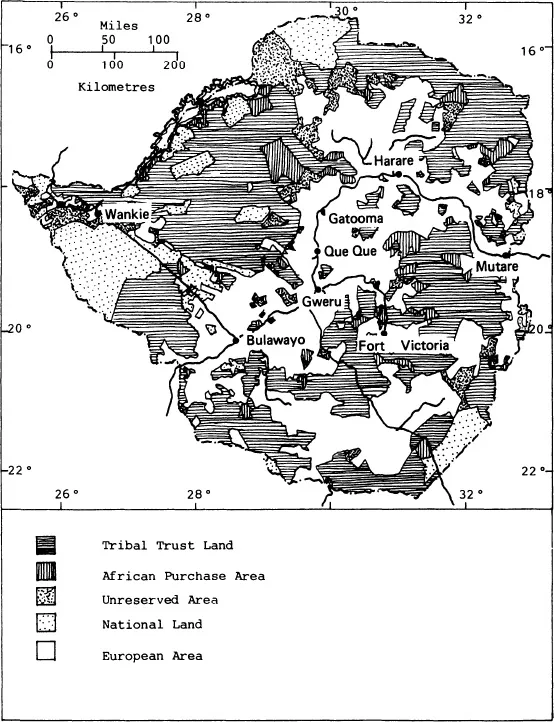

Gradually, as European influence grew, racial prejudice against the blacks increased as well, became established and institutionalized. It was expressed clearly in the Land Apportionment Act of 1930 by which the country was divided into distinct areas for black and white habitation. Areas assigned for black habitation were known as Reserves until 1969 and after that as Tribal Trust Lands until independence in 1981. Generally these areas lay in the more arid reaches surrounding the more fertile white controlled region which ran from southwest to northeast (see Figure 1.1).This division of land was made possible by the white referendum of 1922 after which Britain granted self-government to Southern Rhodesia in 1923. Faint awareness of a threat other than that from the indigenous black peoples arose after 1926, and in response to this a small standing army was formed. This force was expanded during the troubled years preceding the Second World War. During this war Rhodesian squadrons served with distinction in the Royal Air Force. After 1945 the armed forces were demobilized. However, during 1947 a largely black unit, the Rhodesian African Rifles, was constituted as the core of a regular Army. The territorial force, on the other hand, was almost entirely white and comprised the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Royal Rhodesian Regiment. The Rhodesian African Rifles saw service in Malaya from 1956 to 1958.

Figure 1.1 Land Apportionment 1968

After the general strike in Bulawayo during 1948, a revision of military policy apparently occurred, since three additional white territorial battalions were formed. Recruits into No. 1 Training Unit were formed into the Rhodesian Light Infantry Battalion in 1961. Two other units established were C Squadron of the Special Air Service and an armoured car unit, the Selous Scouts, named after Courtney Selous, a nineteenth century explorer. (This name was relinquished by the armoured car unit and given to a pseudo-insurgent infantry unit in 1973.)

During 1963 an attempted federation with Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi) ended in failure. This politically ambitious scheme was launched in 1953. Its failure could largely be ascribed to the internal racial policies of Southern Rhodesia and the realisation that these policies were incompatible with a closer relationship to neighbouring black states. Black riots during 1960 increased white intransigence and made them less willing than ever to consider reform. Unrest first broke out in the black townships of Salisbury (now renamed Harare) when three leaders of the National Democratic Party were detained. Over twenty thousand people gathered in protest at Stodart Hall. Prime Minister Edgar Whitehead responded by ordering the distribution of leaflets from the air announcing a ban on all similar meetings. He also ordered the partial mobilisation of the Army. Further disturbances in Bulawayo were also dispersed and gatherings were banned.

During December 1962 the new Rhodesian Front party was elected to power. Since its inception the party had been committed to the entrenchment and maintenance of white supremacy without the involvement of a distant colonial mother. The leader of the Rhodesian Front, Ian Douglas Smith, was elected Prime Minister on 14 April 1964. He was initially elected to the Southern Rhodesia legislative assembly as a Liberal Party member in 1948 but became a founder member of the Rhodesian Front party in 1962. He was a dour speaker who had won little public attention before the formation of the Front. Once elected Prime Minister, however, he gained unprecedented popularity among the white population. This support even endured beyond the war against the insurgents. Two events in particular strengthened the resolve of an increasingly isolated Southern Rhodesia to ‘go it alone’ in an attempt to maintain white supremacy: the massacre of whites in Kenya during the Mau Mau uprising of the early sixties and the election to power of an unsympathetic Labour government in Britain in 1964. So, on Armistice day, 11 November 1965, Rhodesia unilaterally declared its independence (UDI). Although aware of the imminent declaration, Rhodesian black nationalists were totally unprepared to offer any form of organized protest. The small number of blacks sent for training in insurgency warfare by emerging nationalist movements at the time were apparently intended for political propaganda rather than to wage a real revolutionary campaign. Arguably the major nationalist insurgent incident before UDI occurred during July 1964: a group calling itself the Crocodile Gang killed a white farmer at a roadblock in the Melsetter area.

Recruitment and training for an insurgent campaign against the Rhodesian Front government started in 1963. The formation of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in that year in competition with the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU) acted as a catalyst for armed confrontation between the black nationalist forces and the white controlled Rhodesian Security Forces.

The undisputed father and leader of Rhodesian nationalist movements in the late fifties and for many years afterwards, was Joshua Nqabuko Nyangolo Nkomo. He had been elected president of the newly formed African National Congress on 12 September 1957, after the Southern Rhodesian African Nationalist Congress and the City Youth League had united. The African National Congress was subsequently banned in February 1959, but re-emerged on 1 January 1960 as the National Democratic Party. This party, in turn, was banned on 9 December 1961. It reappeared on 17 December 1961, as the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union or ZAPU.

For some months before the formation of ZAPU, Nkomo’s leadership had come under increased criticism. It was alleged that he spent more time abroad, canvassing for the nationalist cause, than in Southern Rhodesia leading it. Further dissension broke out among black nationalists after the National Democratic Party executives agreed to the proposals of the 1961 London constitutional conference whereby only 15 out of 65 parliamentry seats were allocated to blacks. African nationalists reacted angrily to this agreement and forced the National Democratic Party hastily to repudiate the agreement, but the damage to the unity of Rhodesian African nationalism had been done. When ZAPU was banned on 20 September 1962, Nkomo was again absent from Rhodesia. He was persuaded to return only after considerable pressure from his own followers as well as from President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. After his release from 3 months’ restriction, Nkomo persuaded the former ZAPU executive to flee with him to Tanzania and there form a government in exile. Bitter dissension about the leadership of the Rhodesian nationalist movement now arose amongst prominent black nationalists including the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and Robert Mbellarmine Mugabe. In response, ZAPU President Nkomo suspended his executive council and returned to Rhodesia to form the interim People’s Caretaker Council. Outside Rhodesia the People’s Caretaker Council retained the name ZAPU. Nkomo was rearrested and detained until 1974. In spite of his long detention, he was never again seriously challenged as ZAPU president.Nkomo’s foremost critics formed the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) on 8 August 1963 with the Reverend Sithole as interim president and Robert Mugabe as Secretary General. Both ZANU and the People’s Caretaker Council were banned in Rhodesia on 26 August 1964. Mugabe and Sithole were arrested. Although he was released during June of the following year, Mugabe was restricted to Sikombela until his rearrest in November 1965. Both Mugabe and Sithole remained in detention until December 1974.

ZANU sent its first contingent of five men led by Emmerson Mnangagwa to the People’s Republic of China for military training in September 1963. They formed the nucleus of ZANU’s armed wing, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, or ZANLA. Having been actively involved in operations against the Rhodesian regime since 1964 it was thus understandable that Sithole precipitated his own fall from the ZANU presidency during 1969 when he stated in the dock

I wish publicly to dissociate my name in word, thought or deed from any subversive activities, from any terrorist ctivities and from any form of violence.(1)

Internal dissension within the ranks of the black nationalists thus brought about the formation of ZANU. Although Nkomo’s vacillation had discredited him among a large section of the Rhodesian nationalist leaders, he still appeared to command majority black nationalist support within the country at the turn of the decade. At this stage the tribal bias of both ZANU and ZAPU was not as strongly manifested as from 1972 onward.

ZANU and ZAPU, however, increasingly competed in revolutionary zeal and recruitment. The ZAPU armed forces later became known as the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZPRA or ZIPRA)(2)

The insurgents’ strategy at this stage was based on two false assumptions. First, that Britain could be induced to intervene forcibly in Rhodesia should law and order seem in imminent danger of collapsing, and second that

… all that was necessary to end white domination was to train some guerrillas and send them home with guns: this would not only scare the whites but would ignite a wave of civil disobedience by blacks.(3)

By 1966, however, ZAPU, still the major black nationalist movement, had realized that the British government could not be induced to intervene actively in Rhodesia. ZAPU’s armed wing, ZPRA, also recognized that it did not have the ability to force a collapse of law and order. The major task of the insurgent forces existing at this early stage was therefore to convince the Organisation of African Unity and the world at large that the forces to overthrow the regime of Ian Smith really did exist. This was vitally important if financial and political support was to be forthcoming. It was also apparent that if Rhodesia was to become Zimbabwe, Zimbabweans themselves would have to take up arms and fight for it. While leaders of ZANLA and ZPRA were convinced of this, black Rhodesians as yet were not. Rhodesian citizens resident in Zambia and Tanzania were thus forcibly recruited to swell ZANLA and ZPRA ranks until the trickle of refugees and recruits turned into a flood.

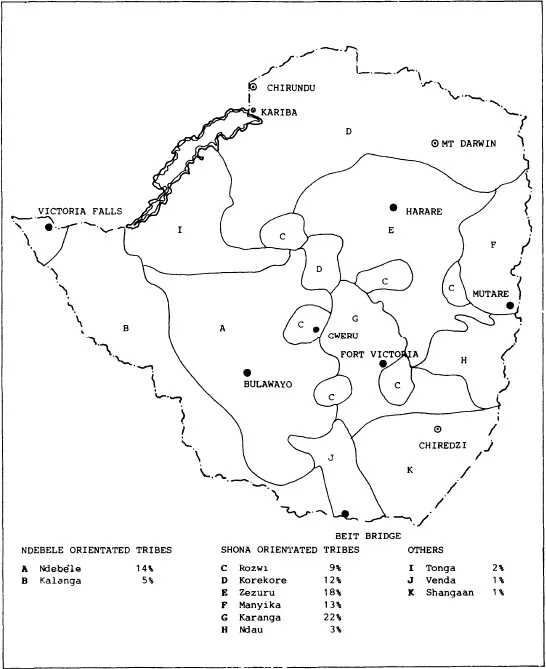

While ZPRA bore almost the full weight of the war effort in these initial years, ZAPU remained at the same time the major exponent of the ‘external manoeuvre’ designed to obtain maximum international support. ZANLA, trained by China, played a very limited military role during this period. Both movements also increasingly appeared to represent a major tribal grouping in Rhodesia. ZAPU had the backing of the Matabeles, who constitute some 19% of Zimbabwe’s black population, while ZANU had that of the loosely grouped Shona nations (77%). (See Figure 1.2)

Following UDI the first military engagement recognised officially by Rhodesia occurred on 28 April 1966 between Security Forces and seven ZANLA insurgents near Sinoia, 100 km northwest of Harare.

That day is now commemorated in Zimbabwe as Chimurenga Day – the start of the war. The group eliminated was in fact one of three teams that had entered Rhodesia with the aim of cutting power lines and attacking white farmsteads. A second of the groups murdered a white couple with the surname of Viljoen on their farm near Hartley on the night of 16 May 1966. The insurgents were subsequently captured by Security Forces. In total all but one of the original fourteen insurgents were either killed or captured.

Shortly afterwards a second ZANLA infiltration was detected near Sinoia. In the ensuing battle seven insurgents were killed and a number captured.

During August 1967 a combined force of 90 insurgents from ZPRA and the South African African National Congress entered Rhodesia near the Victoria Falls. They miscalculated the attitude of the local black population and the Security Forces soon knew of their presence there. In the first major operation of the war 47 insurgents were killed within three weeks and more than 20 were captured. The remainder fled to Botswana in disarray. Fourteen of the Security Force members were wounded and seven others killed.

Early in 1968 a second force of 123 insurgents from ZPRA and the South African African National Congress crossed the Zambezi River from Zambia into northern Mashonaland. The group remained undetected for three months, setting up a series of six base camps at intervals of 30 kilometers before being reported by a game ranger. On 18 March Security Forces attacked and destroyed all of the six camps. During the ensuing month 60 insurgents were killed for the loss of six members of the Security Forces.

During July 1968 a third joint incursion took place. The 91 insurgents involved formed into three groups. About 80 insurgents were either killed or captured at that time and significantly, the first member of the South African Police deployed in Rhodesia also died then. Following the entrance of the South African African National Congress into Rhodesia, members of South African Police counter-insurgency units were detached to the Rhodesian Security Forces. In the ensuing years the Republic of South Africa involved itself increasingly with the security situation on the borders of its northern neighbour.

Figure 1.2 Major Tribal Groupings in Zimbabwe

These first insurgent incursions into Rhodesia all originated from Zambia across the floor of the Zambezi River valley. This sparsely populated area was deemed the natural infiltration route as mobilisation of the masses did not yet constitute an important principle in insurgent strategy. Security Force counter-measures were thus largely track and kill type operations. Furthermore infiltrations took place in relatively large groups, which Security Forces located more easily.

After a peak during 1968, almost no incursions took place the following yea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Abbreviations and Terminology

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction

- 1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WAR FOR ZIMBABWE: 1890 TO 1979

- 2. COMMAND AND CONTROL

- 3. PROTECTED AND CONSOLIDATED VILLAGES

- 4. BORDER MINEFIELD OBSTACLES

- 5. PSEUDO OPERATIONS AND THE SELOUS SCOUTS

- 6. INTERNAL DEFENCE AND DEVELOPMENT: PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS, POPULATION AND RESOURCE CONTROL, CIVIC ACTION

- 7. EXTERNAL OPERATIONS

- 8. OPERATION FAVOUR: SECURITY FORCE AUXILIARIES

- 9. INTELLIGENCE

- 10. THE SECURITY SITUATION BY LATE 1979

- 11. CONCLUSION

- Selected Bibliography

- Index