![]()

1 Sustainability, technology, the media, and us

Sustainability

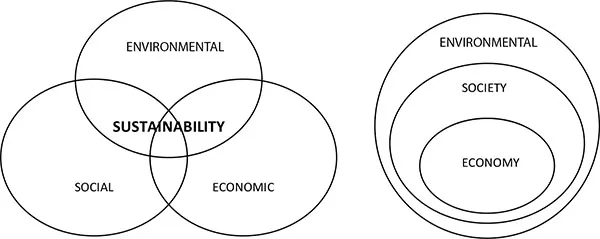

What is sustainability, and how do we choose the best definition out of so many currently available on the Internet? Shall we rely on Wikipedia and subscribe to the diagram of three pillars of sustainability, or shall we opt for the bull’s-eye diagram of three intersecting circles (Figure 1.1), or any one of thousands available to us at the click of the button? The problem is that whatever we choose and whatever we decide to follow, we will still be only scratching the surface of the real issue here. The fact is that the way we live is incredibly unsustainable, whichever definition we will try to follow.

Our quest to understand the concept of sustainability is further clouded by a multiplicity of terms that are proffered as equivalences or clarifications. Both popular press and professional literature uses terms such as “low carbon”, “zero carbon”, “zero emission”, and “minimal waste”, suggesting that our earlier understanding may be missing something. Rather like the diet industry, these terms suggest that if we focus on a specific aspect and work to reduce measure, we will be acting responsibly. We have a propensity to believe in ideas that give us promise of reward, a better quality of life, a better future. As we shall see when looking at the growth of suburbs in the nineteenth century, people were offered a chance of fresh air, free time in the garden, and a better quality of life. They had little hesitation in accepting the promise because the promise allowed them to dream.

Today, however, we find dreaming rather difficult. The images of polar bears on a melting iceberg do not encourage us to dream about the future; rather, they convey a sense of foreboding. The roof of our dream house with solar panels is at best delaying the inevitable but is not an action inspired by a dream.

We know that our lifestyles today are unsustainable; the daily newspapers tell us as much. We are a well-developed and deeply committed consumer society, and we understand that our consumption patterns place burdens on future generations. The data is difficult to avoid or to deny. Addressing this through messages of guilt, conveyed through images that intend to scare us, is having very limited impact in changing the way we live. As much as the majority of us try to be good and reduce energy and water consumption, as well as buying ‘green’ products, we are well aware of the data indicating that the state of our planet is not improving – it is getting worse.

Figure 1.1 Sustainability diagrams

What is our choice? Do we want to follow the path to sustainability as described by the government, activists, or media? Which well-worn choice excites us? The Advertising Age describes sustainability as:

a good concept gone bad by mis- and over- use. It’s come to be a squishy, feel-good catchall for doing the right thing. Used properly, it describes practices through which the global economy can grow without creating a fatal drain on resources. It’s synonymous with ‘green’. Is organic agriculture sustainable, for example, if more of the world would starve through its universal application?

(Lammers 2011)

Society demands more sustainable products. Many of us would like to live more sustainable lifestyles, and unfortunately business and politicians understand only too well how to fulfill our desires for sustainable products and use sustainability for profit and not at all for a shared better future.

Somewhere along the way, sustainability lost its appeal. And maybe that was because the sustainability agenda became useful for political campaigns, manufacturers’ campaigns, and the promotion of products. It is not difficult to see that these agendas usually have very little to do with protection of our environment.

The question is whether we have any chance left to make sustainability an object of desire, or did we lose this chance twenty years ago? The other and probably much more important question is: is technology the only answer to our problems today, or are we living in delusion that technology will allow us to satisfy all our needs today and the needs of our children in the future?

Technology and us – can technology save us?

In “The Paradox of Technical Development” by Paul Gray we read:

Technological development has had profound and permanent effects on the way we live and the way we think about the future – what is possible, what is probable, what is to be feared, and what is to be hoped for.

(Gray 1989:192)

Many of us still hope that technology will come and rescue us from environmental crisis. We keep reminding ourselves that at the end of nineteenth century we were worried about drowning in the horse manure, due to tremendous increase in horse-driven carriages within our cities. The invention of the automobile came to our rescue. Therefore, it is only logical to believe that either the solar-power electric car or some new invention in transport technology will come to our rescue again and we will be able to carry on as before. Changes are never easy, but why worry when technology is there to save us? We have enough evidence around us to make us believe that invention and technology will be able to solve a lot of our environmental problems. Unfortunately most of the time technological innovation presents a solution to a specific problem. But at the same time our understanding of the problem is too simplistic and so is our ability to predict the consequences of particular solution. As a result, the problems that we manage to solve can create multiple other problems. For instance, let us look at innovations related to agriculture. We have been increasing agriculture production for centuries, and without it we would not be able to feed the world. But fertilizers and insecticides have dramatically contributed to chemical pollution of our rivers, lakes, and whole water systems. We still have no methods to properly assess profit related to its damage to the environment.

We now have solar power, wind power, distributed infrastructure, electric cars, smart cars, smart technologies, and we even have smart cities. We invest in bio-mimicry, we try to imitate natural processes, and we are getting better at it. Every year there are more gadgets on the market to help us save electricity, save water, recycle, reduce, reuse. We are getting smarter, but how smart are we really? Or should we remind ourselves of Einstein’s famous quote:

The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them.

The development of the electric car, stackable car, on demand self-driving car, and smart car will not be able to solve the petrol crisis, nor will it reduce traffic on the roads, improve parking in the city, or get rid of the pollution. We may observe temporary improvement, but, as Einstein said, we would be still trying to solve our problems using “same level of thinking we were at when we created them”. Technology might be able to save us, but only if we change the way we think. Can we imagine our economy without growth and, related to it, consumption? Can we get rid of our reductionist way of thinking that tries to solve the problem in isolation and tends to optimize the solution? We all know that when each part of the system is optimized, or each subsystem is designed to be as efficient as it can be, it is likely that the system will underperform (Karakiewicz 2010). We also know that this in turn leads to a lot of other problems. Sharon Beder, in her paper The Role of Technology in Sustainable Development, calls it narrow thinking:

Part of the problem […] is that technologists make their aims too narrow; they seldom aim to protect the environment. […] Technology can be successful in ecosystem if its aims are directed toward the system as a whole rather than at some apparently accessible part.

(Beder 1994)

But, nearly seventy years since Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s (1969) General System Theory, we are now slowly shifting from the machine-inspired age towards the age inspired by nature and living systems. Nevertheless this process is not only very slow but also full of embedded problems, which will be very difficult to resolve. We have technologies today that try to imitate natural processes. But even if we talk about bio-mimicry, as described by life science writer Janine Benyus (2002): innovation described by science, we still most often speak about an individual product. Furthermore, even if we rely on it for inspiration, our response results in fixed propositions, forgetting one of the most important concepts of natural systems: natural systems are never fixed. They are in constant flux, adapting and changing constantly in order to fit the environment. Unfortunately, our understanding of sustainability is reduced to understanding the sustainable products in their final perfect stage, unable to change or readapt. Following this, our so-called sustainable buildings are usually assemblies of sustainable technologies, gadgets, and parts. Our sustainable cities or eco-cities are similar to buildings: designed as machines and full of the latest technologies, which all claim to be sustainable. But the majority of us still find it difficult to understand this complex system, and we heavily rely on the assumption that:

… even very complicated phenomena can be understood through analysis. That is, the whole can be understood by taking it apart and studying the pieces. [And that] sufficient analysis of past events can create the capacity to predict future events.

(Jones 2003)

In the seventeenth century, long before the Industrial Revolution, Johannes Kepler, the German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and key figure in the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, wrote:

My aim is to show that the celestial machine is to be linked not to a divine organism but rather to a clockwork.

(Kepler cited in Holton 1973: 72)

This celestial machine model became a prototype not only for assembly lines in factories, which started to appear before the Industrial Revolution, but also for all sorts of other organizational models, businesses, companies, and even schools and other institutions. Without any doubt, the Industrial Revolution and machine-age led to an incredible number of innovations and previously unseen productivity and manufacturing speed. But all of these new technologies were also responsible for the creation of a mechanized organizational environment, which tended to segregate, separate, and dehumanize.

Our understanding of science and developments in technology benefited tremendously from these assumptions and the reductionist approach, but if we are serious about saving our planet, a reductionist approach will not be able to save us. Most technological inventions, even if they are designed as systems, are most of the time determined systems, which means that the relationship between inputs and outputs is linear and predetermined (Jones 2003).

New developments in technology always lead to what Joseph Schumpter (2008) calls “creative destructions”, where old industries die and are replaced with new. We have been observing this for nearly three centuries, ever since the development of steam engine, which in the eighteenth century led to an industrial revolution. And all of these new technologies had the similar goal in mind of harvesting natural and social capital in order to create financial and productive capital. We are all aware of the consequences of this reductionist way of thinking, but we still do very little to change it. We still operate within the same mindset: even if we are trying to think about sustainability, we still manufacture products using processes that primarily produce waste. According to Paul Hawken, less than 10% of everything we extract from the Earth becomes useable, and 90–95% becomes waste (Lovins et al. 2008). Not to mention the fact that the product itself will become waste sooner or later. Our reductionist way of thinking that constantly concentrates on labour and finance efficiency has managed to create a highly inefficient system of production (Ayers 1989).

Our preoccupation with parts and objects, rather than systems, or the linkages and interactions between elements, parts, and objects, has dominated our world since Descartes’s scientific reductionism. And unless we start visualizing sustainability not in terms of objects but rather as processes or systems, we will find it very difficult to be sustainable. Even if we discover new technologies, new renewable sources of energy, and other further innovations, we will not be able to change much.

But are we able to step up to a different level of thinking, and what will it take to achieve it? Maybe instead of constantly trying to fix problems and watching the creation of hundreds of new ones, we should start by addressing what caused these problems in the first place. Or as Barry Commoner suggested over thirty years ago, in 1972:

If technology is indeed to blame for the environmental crises, it might be wise to discover wherein its ‘inventive genius’ has failed us – and to correct that flaw – before entrusting our future survival to technology’s faith in itself.

(Commoner 1972:179)

With the Industrial Revolution came our understanding that human health required protection. But this protection was more to do with maintaining the ability to increase productivity than promoting a better quality of life. The idea of searching for a better quality of life enabled by new technologies came later, together with creation of a new middle class.

The move to the suburbs in the late nineteenth century came from the belief that cities were not healthy places to live and that pollution and overcrowding were the reasons for the spread of disease and short life expectancies. People moved to the suburbs in order to find a healthy lifestyle. And it was technology that made it all possible.

The railway radically altered the personal outlooks and patterns of social independence. It bred and nurtured the American dream. It created totally new urban, social and family worlds. New ways to work. New ways of management. New legislation.

(McLuhan 1994)

Development of rail networks made a profound change to the way cities have been designed and the way they work. In addition, technologies made suburban life possible without servants. Electric appliances such as the iron, fridge, cooker, washing machine, and vacuum cleaner made it possible not only to be free of servants but also to create the need for consumption of an ever-increasing number of products. You not only had to have the washing machine, iron, or radio, you needed to have the newest model.

Technology made our lives easier and gave us more time but not to relax or enjoy the garden. It gave us more time to work and consume more. Without any doubt the developments in technology have been going hand in hand with the increase of consumption, and this has gradually led us to our environmental crisis. Cars, plastic, fertilizers, even antibiotics were developed in order to make our lives better, easier, healthier. Today we are slowly coming to realize that technologies have maybe set their aim too narrow. As innovation in the form of new products comes into a market those products often become popular and start to erode the previous dominance of other products. The invention of the car replaced horse-driven carriages and saved us from drowning in horse manure, but at the same time stopped us from walking. It made it possible for us to live farther from the city centre, to move to suburbs, but it also made us dependent on cars, petrol, and commuting. It made us consume more land, energy, and water to build more infrastructures and as a result produce more waste, pollute our environment, and make us unsustainable.

We are now slowly becoming aware of consequences of our actions and behaviours. In recent years we have also started to view innovation as a system with principles that govern its operation and not as a distinct product. And more recently some, like...