![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Marx’s critico-theoretical writings: structures and issues

This book focuses on what will be called Marx’s critico-theoretical writings. These encompass only part of his total bibliography, but they do contain his main contributions to intellectual history.

The writings included under this rubric are those in which the analyses are the results of Marx’s preoccupying intellectual activity, namely the pursuit and propagation of a critical comprehension of the nature and operations of capitalism as a social system that functions through human inequity and oppression. He sought to expose the immanent ‘laws’ of capitalist evolution and its ultimate and inevitable demise by means of applying the weapon of theoretical criticism against false intellectual images of the system, most especially those perpetrated by the writers of political economy.

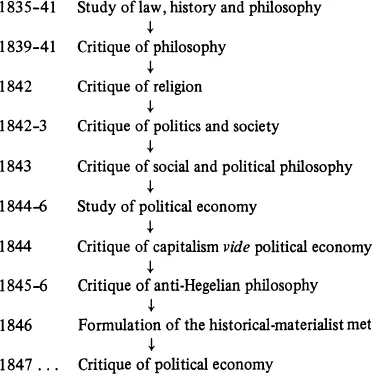

The progressive evolution of Marx’s use of the critical method may be summarised schematically as follows:

The stages of this progression are designated by Marx’s critical object. Three such stages can be discerned up to 1844. First, the stage of the abstract critique of philosophy and religion which was confined to Marx’s time at university and immediately afterwards. Second, his first work as a journalist in 1842–3 brought him into contact with the human issues of social, political and economic life. These became his immediate focus in a series of important critical articles. Third, he sought a more theoretical framework for his social critique through a critical reading of the social and political philosophy of Hegel.

Then, in late 1843, Marx ‘discovered’ political economy and found in it the essential anatomy and physiology of contemporary society. After reading the young Engels’s article, ‘Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy’, in one way or another political economy became the focus of Marx’s critico-theoretical endeavours throughout the rest of his life. There was one apparent digression from this path in 1845–6 when he sought to distance himself from the contemporary trends in purely philosophical critique. This ‘digression’, though, became an integral part of the evolution of Marx’s critique of political economy in that it led him to formulate the principles of historical materialism which subsequently provided the methodological core of his thought.

Marx’s first studies in political economy led him to a critical comprehension of the nature and operations of capitalism through political economy rather than to a critique of the analyses of the system that he encountered. His first exposition of the critical theory of capitalism in 1844 emphasised the immediate human ramifications of living under the domination of capital. In 1847 and beyond, but most especially in 1857–8, Marx’s critical object became the analyses of capitalism in which the political economists portrayed, to varying degrees, a false and apologetic intellectual image of the system. Through this critique of political economy, Marx endeavoured during the rest of his life to formulate and propagate a critical theory of the essential nature and immanent evolution of capitalism.

In tracing the bibliographical dimensions of the evolution of Marx’s critical thought, a chronological periodisation will be used:

before | 1844 |

1844 to | 1856 |

1857 to | 1860 |

1861 to | 1883 |

beyond | 1883 |

A chapter of the book will be devoted to each of these phases. It must be emphasised that while this chronological division has a sound rationale, as the argument in the text of the book will make clear, it is not to be taken to imply anything per se about the complex issue of the nature of the evolution of Marx’s critical theory. These phases certainly do not represent periods of intellectual discontinuity. Indeed, a premise upon which the work in this study is founded is that Marx’s critical theory evolved organically and dialectically and not through any series of quantum jumps.

Beyond the pedagogic benefits of a detailed and accessible chronological analysis of Marx’s writings in critical theory, more profound issues of Marx scholarship are exposed by this analysis. The careful study of Marx’s accumulating bibliography reveals evidence pertaining to several such issues. First, it is revealed that there is some difficulty and consequent confusion about the dating of Marx’s first studies and writings that centre on political economy. Second, the evidence available suggests that while Engels’s 1843 article, ‘Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy’ undoubtedly acted as a catalyst in stimulating Marx’s concern with political economy, it in no way defined or bounded the study that Marx undertook. Third, there arises the complicated but important issue of the dynamics of Marx’s bibliography in critical theory. His plans for his complete critico-theoretical project underwent continual change as the project evolved. The complexity of these changes in scope and analytical organisation is considerable and has significant implications for the interpretation of the precise nature of the methodological and substantive evolution of the critico-theoretical core of Marx’s thought. Most especially do these changes involve the fate of the ‘Six-Book plan’ that Marx initially formulated for his complete critique of capitalism. Opinion about this fate affects profoundly the interpretation of the status and situation of Capital in the critique. Fourth, an issue that is an integral part of the dynamics of the plans just referred to concerns the fate of the 1857 ‘Introduction’ manuscript, Marx’s only explicit endeavour to set down the methodology of his critical theory as it developed from the basic tenets of historical materialism. His subsequent apparent rejection of the piece complicates further the task of comprehending the implications of these bibliographical dynamics. Fifth, and again associated with the dynamics of Marx’s bibliography, is the puzzle of his failure ever to complete most of what he set out to write. The evidence available suggests that this fact, and possibly much of his indecision about the scope of his critique of capitalism, stemmed from an extreme self-consciousness about the problem of presenting his work. The requirement was that it would be widely read and understood, for its very raison d’être was the formation of a uniform proletarian consciousness as the theoretical foundation for the revolutionary transcendence of capitalism. If the presentation failed to achieve this impact, then Marx’s life-work as the theorist of revolution failed too.

As a result of considering the bibliographical evidence pertinent to these issues, several important, interdependent conclusions are indicated. These affect profoundly the approach to be adopted when studying Marx’s critico-theoretical writings. First, the totality of Marx’s critical theory involves an evolving methodological and substantive structure that can only be comprehended within a chronological frame of reference. This evolution consists of elements of both continuity and change interwoven in a complex pattern. Second, a-chronological, non-evolutionary readings of Marx’s writings are most inappropriate in the light of this dynamic complexity. Pieces from different phases in Marx’s intellectual development are not able legitimately to be assembled into an holistic interpretation. Third, readings of Marx’s writings that emphasise one phase of his thought to the exclusion of others must fail to comprehend fully the scope and significance of his total contribution to intellectual history. Finally, the common practice of studying Marx’s thought by reading Capital only is potentially misleading in two senses. One is that the work is an incomplete guide to the totality of his critical theory of capitalism. The other is that such a reading must be tempered by a full appreciation of the bibliographical, methodological and substantive situation and status that can be ascribed to the work. This is a complex and controversial issue, but the evidence that is elicited below reveals that Capital is an unfinished climax to an ambiguous critico-theoretical project of uncertain dimensions. It certainly cannot legitimately be read as a definitive or axiomatic statement of Marx’s critical theory. In this assessment, it is as well to be mindful of Marx’s reported reply to the young Karl Kautsky when he asked about the publication of Marx’s ‘complete works’. Marx’s response, so the story goes, was that they would first have to be written! This anecdote has a ring of prophetic truth when the assembled bibliographical evidence is considered.

In spite of the profound significance of the bibliographical framework within which Marx’s thought developed, a reading of the Marxological and Marxist literature reveals that very few writers have devoted much attention to the complex details involved.

The most substantial efforts made so far in this field have been those of the French Marxologist Maximilien Rubel. The results of his research comprise many articles and books, together with collections and translations of Marx’s works, all originally available only in the French language (with one or two pieces in German). English readers now have access to his book Marx Without Myth: a Chronological Study of His Life and Work (written jointly with Margaret Manale) published in 1975 and to some of his key essays published as Rubel on Karl Marx: Five Essays in 1981. The former work is mainly biographical, although the chronology of Marx’s life includes consideration of some bibliographical details and issues. Two of the essays in the latter work are more directly bibliographical. One of these, ‘A History of Marx’s “Economics”’, originated as the Introduction to the volume of Marx’s works edited by Rubel and published as Oeuvres: Economie II in 1968. The other, ‘The Plan and Method of the “Economics”’, was originally published in the journal Etudes de marxologie in October 1973. Each deals with important issues of structure and method in Marx’s thought as it evolved towards Capital. My work takes account of the insights provided by Rubel, but I treat the bibliographical structure of Marx’s critico-theoretical writings in more explicit detail and raise issues not evident in those of Rubel’s contributions available in English.

One other substantial treatment of Marx’s bibliography should be mentioned. Roman Rosdolsky’s book, The Making of Marx’s ‘Capital’, published in English in 1977, includes two chapters that deal with this topic. In these chapters, Rosdolsky provides some important analyses of the bibliographical puzzles, and their substantive significance, raised by a study of Marx’s writings leading up to Capital. A reading of Rosdolsky’s work has provided valuable guidance for the present development of my original researches, most especially with respect to the dynamics of Marx’s plans for his work.

Several other works that deal with Marx’s bibliography more or less specifically are much less substantial and cover in brief the same grounds as those covered by Rubel and Rosdolsky. The most important of these are: Salo Ryazanskaya’s Preface to Marx’s Theories of Surplus Value (TSV, I, 13ff.); Vitali Vygodski’s book, The Story of a Great Discovery: How Karl Marx wrote ‘Capital’; Ben Brewster’s article, ‘Introduction to Marx’s “Notes on Machines”’; David McLellan’s biography, Karl Marx: H...