![]()

1 Introduction

Water, as we know, dissolves more substances than any other liquid, known as the ‘universal solvent’, wherever it flows ‘it carries substances along with it’ (Altman 2002: 10). This analogy is particularly poignant in the Baucau Viqueque region of Timor Leste, which like much of the rest of the island, is underlain by karst formations. In such environments the topography is formed chiefly by the dissolving of rock by water and complex and changing surface and subsurface water pathways are always in the process of ending or becoming. Earthly substances are always on the move.

In the course of carrying out research for this book, I slowly came to understand another reality: that in this particular karstic landscape the subsurface waterworld carries with it and is inspirited by aspects of a sacred and animate cosmos. In the material reality of this society, such water is the life-nourishing milk and blood of the earth and a key medium of communication between the visible and invisible worlds, the worlds of light and dark. Emerging from springs into the light of the surface world, karst water carries with it, mediates and transforms the spiritual essences of both life and death.

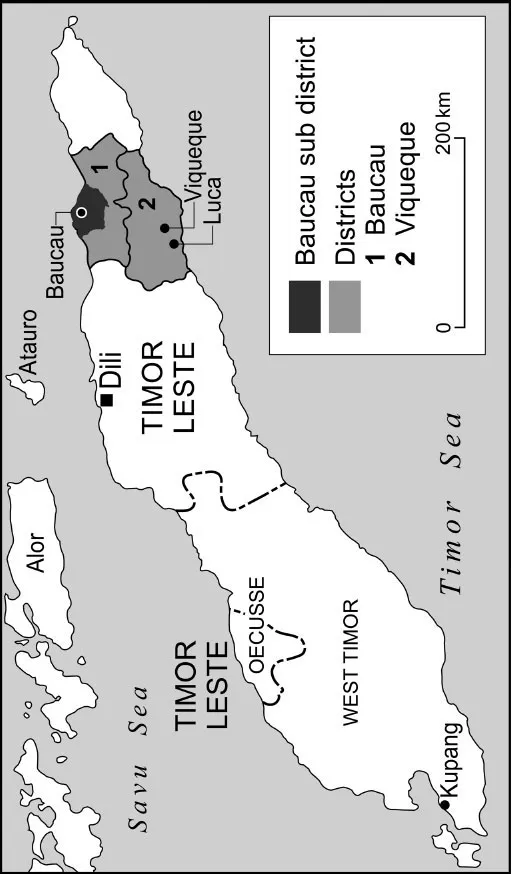

Drawing on primary ethnographic research carried out between 2004 and 2014 in the eastern districts of Baucau and Viqueque (population 182,000 (NSD and UNFPA 2011); see Map 1.1), this book is an important contribution to the recent resumption of anthropological work in post-independence Timor Leste (McWilliam and Traube 2011). It examines the spiritual ecology and associated hydrosocial cycle of a water focused society, following the trails of water and water associated spirit beings travelling through the karstic landscape from the mountains to the sea. It argues that in this hydrosocial cycle the material reality of water is critical to the ways in which local agricultural communities create and maintain place, to their understandings of space and social relationships and to their particular cosmopolitical configurations of life and being. This supra-social landscape (where the social is not confined to the domain of human beings) was created by and still governed through complex interactions between spirits, humans, animals and other physical objects and forces. Laying out in a ‘perspicuous’ view (Wittgenstein 1979: 9e) my own ethnographic data and interpretation, this book tries to answer questions about how water is perceived, managed and used in this region of Timor Leste and how local people’s own understanding of their past and future trajectories are linked to their particular understandings of the significance of water. It then considers how these local realities engage with and are today co-constituted by modernist technologies of water governance.

Map 1.1 Baucau Viqueque zone of Timor Leste (copyright Chandra Jayasuriya).

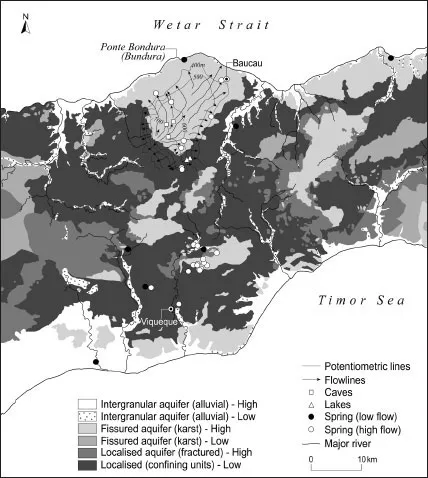

The Baucau Viqueque zone is divided in its central region by rugged forested hills and mountains splitting on either side into tracts of savannah and coastal areas replete with limestone terraces, caves, outcrops, sinkholes, depressions, springs, subsurface drainage and subsurface rivers of which, until recently, little was scientifically understood (cf. Metzner 1977). In order to better locate and potentially access these groundwater resources, in the late 2000s hydrogeological research was systematically carried out in Baucau by scientific advisers to the Timorese government (Furness 2011, 2012; Wallace et al. 2012a; see Map 1.2). The karst limestone formations of the Baucau Viqueque zone vary greatly in age between the ancient mountains of the central Mundo Perdido range to the much younger Pleistocene raised coral reefs of Baucau plateau and marine terrace zone (Audley-Charles 1968; Wallace et al. 2012a).1 Impermeable clay formation separates these two zones.

Water flowing through the younger karst of the Baucau plateau region does so via a ‘two phase flow system’ (Furness 2012). After rain water enters the weathered rock and thin soils, water flow is activated initially through the porosity of the limestone. The second phase of flow is through the secondary karst features of sinkholes, dolines, caves and enlarged fractures. While the initial flow through the limestone is diffuse, connected to the secondary porosity features and flows are large springs which are potentially high yielding (Furness 2012: 3; see Map 1.2).2 While the region has a pronounced wet season, in some springs such as Wai Lia in Baucau, the annual flow cycle is stronger in the dry season (June–October). This is counter-intuitive and suggests a long time lag in the water’s underground flow.

While these hydrogeological surveys (2010–2012) produced much important information on the local hydrology, there was no attempt to understand how the karst water flows and landscape was configured in local cosmological and socio-ecological terms. Yet my own research, intensively carried out during roughly the same period, makes it clear that from a local perspective this entire karstic landscape forms a culturally connected web of seepages and deep underground water pathways stretching from the central mountains, to the plateau, marine terrace zone and eventually to the sea.

Located in the heart of the ancient contact and collision zone between the migrating pacific peoples of Melanesia and Austronesian seafarers from southern China, most inhabitants of the Baucau Viqueque zone speak one or more of the Makasae, Kawamina and Tetum languages.3 In contrast to the Eastern Tetum (Hicks 2004 [1976]), little ethnographic work has been carried out with Austronesian Waima’a (a ‘dialect’ of the Kawamina language group) and non-Austronesian Makasae speakers.4 Taking seriously the import of their localized place making histories and social relations with water, as this book unfolds I carefully consider the ways in which this waterscape, associated topography, underground pathways and meteorological phenomena are interpreted and interacted with. I draw out distinctive regional narrative genres relating to house-based origins, settlement and spring water and argue that spring water has, and continues, to play a central role in contestations over power and place. I explore the way narratives told as village and ‘house’ histories, as well as religious practices carried out at and around springs, continually transform and reverberate across time and space as common myths and practices linked to particular places (which are linked in turn to other places and islands across the region). I argue that taken as a whole, they make clear the all-encompassing meaning and significance of water across the zone and the variables that continue to influence local religious practices and water governance outcomes. In the final chapters I investigate how these localized narratives and associated practices intersect with mainstream colonial and more modern histories of development and exchange across the region.

Map 1.2 Hydrogeology of the Baucau Viqueque zone (copyright Chandra Jayasuriya, adapted from The Hydrogeology of Timor Leste map, copyright Geoscience Australia (Wallace et al. 2012b)).

Understanding that spring water is a critical element through which people relate to one another and the landscape, the book also traces the import of water to the ancient production of wet rice, examining complex social, political, economic and environmental fluidities and continuities across time and space. With the independence era opening up a space for the resurgence and renegotiation of these relations, I argue that despite the neoliberal governance agendas of others, local people continue to foreground and engage with the foundational customary economy under whose auspices water’s spiritual agency is activated and local water politics plays out. In these dynamic and opportunistic processes I argue we can locate a new ‘politics of possibility’ (Gibson-Graham 2006) for alternative modes of environmental governance and economic development.

Modernizing water governance and the place of custom

Coming to its present form in 2002, independent Timor Leste is recognized as one of the most significant contemporary international experiments in building the state from the ground up. With a population and landscape deeply scarred by a tumultuous and complicated colonial history, Timor Leste is a post-conflict state struggling with enormous development challenges. Following centuries of Portuguese missionizing and colonial rule, the often bloody military and bureaucratic occupation of the country by Indonesia from 1975 (Gunn 1999) resulted in the disruption of Timorese land uses and lifestyles through ongoing military surveillance and conflict with Timorese resistance forces (CAVR 2006). During this period the Timorese suffered abuses of human rights, and the widespread loss of life5 and property (CAVR 2006; Tanter et al. 2006; Nevins 2005). Hence independent Timor Leste faces complex social and economic challenges as it attempts to rebuild itself as a modern nation state (Fox 2001; Fox and Babo Soares 2000; Hill and Saldanha 2001; Philpott 2006; Scheiner 2014). Since 1999, numerous United Nations peacekeeping and state-building missions (between the periods of 1999–2002 and 2006–2012) and the independent government of Timor Leste (2002–present) have continued to struggle with enormous development and reconstruction challenges. Timor Leste is one of the five poorest countries in Asia (Pasquale 2011). Some 41 per cent of the population lives below the national poverty line, and adult literacy is only 50 per cent (UNDP 2009). The tiny half island state is characterized by ecological and cultural diversity: a collision zone for an array of little studied (hydro)geological formations and languages6 and a region of ever changing ecological habitats on which depend multitudes of small-scale livelihood practices and cultures. Most of the million or so Timorese live in rural areas, and they practice traditional near-subsistence agriculture, and depending on their geographical context, fishing, hunting, gathering and some cash cropping (UNDP 2009).

As quickly as the 1999 violent withdrawal of the Indonesian occupiers destroyed the formal governance systems and infrastructure of the country, it also heralded a large-scale, intensive development intervention by the United Nations, international donors and organizations. The lingering effects of this more than decade long intervention has exerted an unparalleled influence on the nascent nation’s development priorities and agenda (Peake 2013). Nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of water governance (see Jackson and Palmer 2012). In the post-independence era, with water and sanitation services either non-existent or in critical disrepair across much of the country, the Timorese state and its international advisers began the long process of developing much needed national water laws and policies. From the outset, the new Timorese constitution claimed all water resources as the property of the state, and donor banks and countries supported resource assessments to better understand the characteristics and limits of water resources (Furness 2004; Asian Development Bank 2004; Costin and Powell 2006; Wallace et al. 2012a). Developing laws and policy are based on the widely accepted global best practice of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), defined as ‘a process which promotes the co-ordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems’ (UNEP-DHI Centre for Water and Environment 2009). Yet in this flurry of activity and knowledge building, much less was done to understand the critical importance of water within the vibrant and enchanted ecologies of Timorese lifeworlds. Likewise, even as donors despaired at the reality of local water and sanitation projects which seemed to fail almost as quickly as their success had been proclaimed (Schoffel 2006), little interest was shown in understanding why it was that localized water sources remained much as they had always been: wellsprings of community wellbeing and revered sites of emplaced identity and custodial responsibility, as well as key sites of resistance and empowerment in the face of ‘outsider’ transgressions. The contention of this book is that this critical ‘oversight’ was and continues to be driven by the failure to engage politically with what I am calling localized spiritual ecologies.

The lessons of this book, drawn against the backdrop of indigenous worlds colliding and enmeshing with new regimes of governance in Timor Leste, resonate across many post-conflict societies, and indeed for modern water governance regimes more generally they are highly topical. The importance of the rights of local and indigenous peoples, and how exactly those rights are configured and formally recognized, remains one of the most vexing questions in state water governance regimes at all stages of modernity (Jackson and Palmer 2012). Across the globe, indigenous peoples, broadly defined, have systematically lower access to water services than non-indigenous peoples (Jiménez et al. 2014). Moreover, if we take the question of ‘what it means to be and become human today, in dynamic relationship with non-human worlds’ (Sullivan 2009: 24) as one of our most pressing problems (Bakker 2010; Latour 2009; Smith 2007), then the task of making visible and legible alternative ways of being in and knowing the world is critical.

In some countries long-standing practices and beliefs around water and its management have survived the colonial and modern period and continue to exert a significant influence over the contemporary management of these localized water systems (Jackson and Palmer 2012; Jackson forthcoming; Bakker 2007). Diverse customary institutions continue to govern the sharing, distribution and consumption of water in many countries (Jackson and Palmer 2012; cf. Madaleno 2007; Lansing 2007 [1991]; Jackson and Altman 2009; Langton 2006; Boelens 2014; Gachenko 2012; Rodriguez 2007). Yet even when they are formally recognized in law, the majority of these laws treat superficially customary rights and interests, relegating them to ‘a legal limbo’ where they are dealt with by ‘basically separating them out of the mainstream “modern” water rights regulated by statute, and by creating a separate legal space f...