![]()

Introduction

For as far back as most residents of Yanbu and Jubail can remember, their small villages have remained largely unchanged. Each lies near a body of water – Yanbu on the Red Sea and Jubail on the Arabian Gulf. The inhabitants are involved primarily in fishing and some maritime trading on a small scale; the villages are dusty and far from the mainstream of the major commercial and governmental centres within Saudi Arabia. Today Yanbu and Jubail are even dustier with the nearly ceaseless comings and goings of trucks and equipment, and the noise-level of the once sleepy towns has risen so quickly and to such a pitch that it would be understandable if the local people were beset with a feeling of unreality.

Saudi Arabia is involved not in a move or thrust, but a stampede toward economic development; the transformation taking place in Yanbu and Jubail perhaps best epitomizes this almost cataclysmic restructuring of an economy on an unprecedented scale and with dizzying speed. The construction of industrial complexes at these Red Sea and Gulf sites is the most massive new undertaking of its kind worldwide. The impact of the vast Yanbu and Jubail facilities will first be felt in the 1980s when some production will begin.

The larger complex is being established at Jubail, which lies some 55 miles to the northwest of Dhahran, the headquarters of the Saudi oil industry; its cost could run as high as $70 billion (US) for the basic infrastructure and industrial plants. Both sites will have petrochemical facilities, refineries, smaller-scale industrial plants and permanent housing; Jubail, in addition, is scheduled for an aluminium smelter, steel mill, international airport, two deepwater ports, power-generating units, telecommunications, as well as the largest desalination plant existing globally. Once a community of about 4,000, Jubail is now swarming with workers from, literally, all over the world. Obviously, Saudi Arabia is rich in two of the most critical elements required for such industrial development – capital funds and access to sufficient cheap energy and petrochemical feedstocks in oil and natural gas.

The development of Yanbu and Jubail falls under the authority of a Royal Commission created specifically to handle this major enterprise. In its annual report for 1977 the Commission delineated the prevailing thinking within the country on the projects and, in fact, on the objectives of the development process itself.

To continue exporting our oil wealth in its crude form, to the point of total depletion, would have adverse economic effects in the not-too-distant future. For then the Kingdom would find itself with no economic basis to rely on.

Thus our industrialization strategy aims at the long-term objective of diversifying the Kingdom’s industrial base, thus enabling Saudi Arabia to realize a greater measure of economic self-sufficiency and allowing it to reap the benefits of local production.1

Whether the Yanbu and Jubail project targets can be met on schedule, and indeed, those of the $142-billion Second Development Plan (1975–80) and the $235-billion Third Development Plan (1980–85), depends not only on the availability of capital and energy. There exist a number of relatively severe constraints in physical and supporting infrastructure and especially in human resources, both quantitative and qualitative. Thus, the drive for industrialization must be long term in that the transfer of technology is time consuming. To this end, the Saudi policy in education has been to train as many citizens as quickly as possible. By the opening of the 1980s as many as 13,000 Saudis may be in the United States alone for university and specialized training. Within the Kingdom 20 per cent of the population was enrolled in some form of education, with 1.24 million enrolled full time. Some 44,000 of these students were attending universities, intermediate colleges, or post-graduate institutions. The projected figure for the end of the Third Plan period (1985) was some 69,000 students in higher education with 10,090 graduates. Considering the population of Saudi Arabia (in the neighbourhood of 7 million), the enrolment and education statistics carry great importance for the coming years and for the development process.

The construction boom is not limited to the industrial centres, as in Yanbu and Jubail. The skylines of Riyadh, Jeddah and other cities are clouded with cranes and rising steel skeletons. If one can be excused a pun, then the national bird of Saudi Arabia certainly should be the crane. In fact, about the only non-Saudi city where the hustle and bustle of a boom-town can be seen on the same scale as Riyadh is in Casper, Wyoming (USA), where the building and overall feeling of barely contained vigour are generated from the oil, coal, and uranium activities and associated growth in this American energy centre.

In recent years much world attention has riveted on Saudi Arabia, heretofore largely ignored but destined now to retain its new prominence throughout the 1980s and 1990s. There are many causes, but a brief listing would include: (1) that country has been a leading ally of the USA and the West in holding down increases in world oil prices since 1975; (2) more than any other producer, Saudi Arabia, possessing the world’s largest reserves of this resource, has been instrumental in meeting the incremental demand for oil; (3) it is the number-one supplier of petroleum to the United States; (4) the Kingdom has the second highest monetary reserves in the world; (5) in terms of gross national product, Saudi economic aid is one of the highest proportions extended by any donor nation; (6) the country has been a major moderating influence not only within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), but within the politics of the Middle East; and (7) Saudi Arabia is the fastest-growing market in the world.

Until the beginning of the 1970s, when the Arab oil embargo catapulted the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the apex of the world energy market, little had been written about the economy of that nation and its people. Tales about the land, its inhabitants and ancient heroes, such as those retold in the Arabian Nights, have existed of course for generations. Also, Saudi Arabia has been regarded as the guardian of the Islamic religion by all Muslims, many of whom strive to make a pilgrimage to the holy places in Mecca and Medina at least once in their lifetimes.2 Interest in the holy land has increased in recent years beyond the level of religious belief. Saudi Arabia is now called upon to play strategic roles in the world of energy, specifically in the activities of OPEC and OAPEC (Organization of the Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries), and in international monetary arrangements. The share of the Kingdom in total world oil exports and reserves and its large investments in OECD countries (particularly the USA) all add up to make Saudi Arabia a very critical country, or a kind of a super oil power, not only to policy-makers but also to the people of developed market economy nations, whose life-styles could be changed by decisions in Saudi Arabia. One should not forget Saudi contributions to development aid to needy countries, Arab economic co-operation, and the Middle East war and peace efforts by serving increasingly as a vital source of finance.

A study on the economy of Saudi Arabia is not just an academic exercise. It must necessarily seek to analyse the domestic development programmes, policies, and political, social, financial and economic structures, with a view to drawing implications for the vital roles which the Kingdom has come to play in the international economic scene. Such is the objective of the analysis contained in this volume.

At the risk of sounding apologetic, the author observes that this study is first and foremost constrained by the paucity of data which, therefore, has generated a host of non-quantifiable magnitudes. Yet there has been an attempt to provide as detailed an analysis of the various sectors of the country as possible. Before a turn is made to detailed analysis, a brief overview of the land, the people and the economy should set the stage.

The Land

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia comprises the bulk of what is commonly known as the Arabian peninsula and has a land area of about 2.3 million square kilometres.

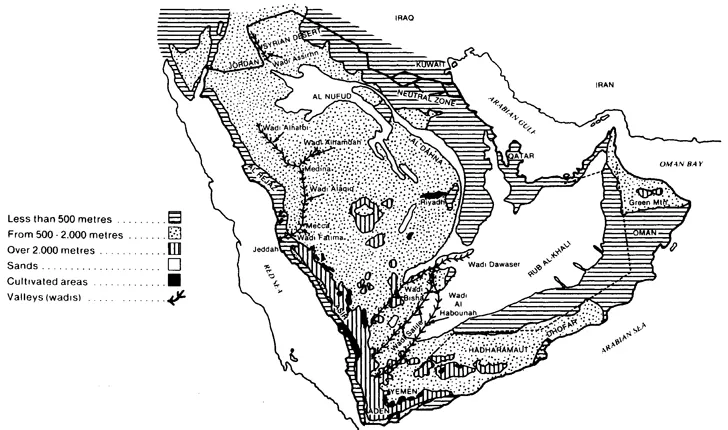

Saudi Arabia is bounded on the north by Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait; on the south by North and South Yemen ; on the west by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba; and on the east by Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and the Arabian Gulf (Figure 1.1). The Red Sea washes a narrow strip of low land whose width varies from 10 to 40 miles. These western coastal plains which are called ‘Tihamats’ are unique in their extensive marshlands and lava fields. To the east of these plains a range of mountains runs, broken here and there by wadis or valleys. Among the wadis, most of which have oases, the most important are Al-Himdh, Yanbu, Fatima, and Itwid and Bisha in the Asir region. The mountain ranges decline towards the coastal plains (i.e. to the west), enabling flood waters to wash silt onto the plains; thus, the soil in this region is kept more fertile than that of any other part of the Kingdom.

The Asir region has the highest peaks in the country, rising to over 2,743 metres. The Mecca region follows with about 2,438 metres declining to 1,219 metres above sea-level in the western Mahd Adh-Dhahab and to 914 metres in the Medina region. The mountain range also extends to the northern part of the country. The Najd plateau lies directly to the east of the northern section of the mountain range. The plateau which continues southwards to Wadi Ad-Dawaser and runs parallel to the Rub al-Khali has an average elevation ranging from 1,219 to 1,829 metres. The northern portion of the Najd plateau consists of plains which extend about 1,448 kilometres beyond Hail to join the Iraqi and Jordanian borders. The sandy hills of Nafud are dry and have no vegetation until rainfall changes the land into temporary grazing pastures.

Figure 1.1: Physical Features of Saudi Arabia

Source: The Kingdom of Saudia Arabia, Central Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Year Book (1974).

Only after the discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia did attention shift to geological studies, which seek to discover the mineral wealth of the land other than oil; only recently a geological survey of 65 per cent of the Precambrian Arabian Shield (located in the western part of the country) was completed. The study has revealed substantial deposits of other minerals. Therefore, in addition to oil, the Kingdom may have respectable assets in copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, iron, phosphates, uranium, and potash; major efforts are required to develop the metallic minerals to reach operational stage. There is, however, commercialization of non-metallic minerals such as cement, gypsum, lime, marble, and salt. Figure 1.2 shows the distribution of mineral deposits in the Precambrian Arabian Shield of the Kingdom.

Most of the land is desert, and water is the most scarce input in both production and consumption activities. Since the land comes under the influence of a subtropical high-pressure system, rainfall is generally very sparse. Summers are hot and dry, while during the winter the occasional inflow of a cold system from the Siberian region cools the temperatures across the country. The winter is thus mostly cold and dry during this time of the year. An exception to this climate picture is the coastal plains which are also unlike the interior regions that experience extreme high temperatures with large daily variations, especially during the summer. Most of the rainfall o...