![]()

1 General problems in psychological measurement

If we are to arrive at a scientific understanding of personality based upon measurement, it is clear that our measures of personality must be at least adequate. Before we can discuss the manifold problems of personality measurement it is necessary first to deal with more general problems of psychological measurement, for it is in the light of these that personality measurement can be assessed.

The use of scales

The aim of measurement is to produce an accurate score on some variable. To take an example from personality, we might want to measure anxiety. In clinically based theories of personality, such as psychoanalysis, anxiety is highly important. Clinicians regularly describe their patients as ‘unanxious’ or ‘highly anxious’. Such descriptions imply measurement. The aim of a quantified, scientific psychology of personality is to make such implicit measurement explicit and precise. In attempting to measure anxiety, a number of different scales or scaling procedures can be used.

Nominal scales

In nominal scales subjects are classified into different categories with no implication of the quantitative relationships between them: typical examples are male/female or socialist/conservative. This is a highly primitive form of measurement, creating only two groups. It is to be noted, however, that even in the discrete categories of our examples an underlying continuum may be discerned. Thus, males and females can be seen as the poles of the male-female continuum, the population being bimodally distributed. Similarly, conservatives and socialists could be seen as lying on a dimension of liberalism. Obviously, nominal scales have little place in psychological measurement.

Ordinal scales

In ordinal scales, as the name suggests, subjects are ranked on the variable being measured. Since ranking implies that we do not know the units of the measuring scale, an ordinal scale is again (as with nominal scales) a primitive form of scaling.

Interval scales

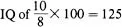

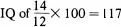

In interval scales all differences of the same size at any point in the scale have the same meaning. For example, in the old-fashioned method of assessing the intelligence quotient, the measured mental age was divided by chronological age and multiplied by a hundred. The problem with this kind of scaling should be clear, and it illustrates the importance of interval scaling. Thus an 8-year-old child has a mental age of 10. This gives him an

. However, a 12-year-old child with a mental age of 14 has an

. Now, in each case an improvement of two years in respect of mental age over chronological age results in different intelligence quotients. The point is that, rightly or wrongly, the scale of measurement has intervals of unequal meaning at different points in the scale. This fact clearly makes the interpretation of scales with unequal intervals difficult and statistical analysis meaningless. Interval scales, however, allow of statistical analysis and comparison between different scales and hence are a minimum requirement for psychological measurement.

Ratio scales

Ratio scales are interval scales with a meaningful zero. Although this point may be hard to conceptualize for many psychological variables, there are methods of test construction which enable ratio scales to be constructed, and these will be discussed below in appropriate chapters.

Clearly, therefore, it can be seen that good psychological testing (indeed, any form of measurement) demands at least interval scales and, ideally, ratio scales. Many tests yield scores which have never been shown to fit our definition of an interval scale. Generally, this is simply assumed, and if sensible results can be demonstrated using the test on the assumption that it is an interval scale, then it is arguable that such presumptions are tenable.

From the viewpoint of the measurements of personality, we must demand from our tests that they yield scores that are either ratio or interval scales or can reasonably be assumed to be such.

Psychological tests must be reliable, valid and discriminating.

Test reliability

In psychometrics reliability has two meanings. A test is said to be reliable if it is self-consistent. It is also said to be reliable if, on retesting, it yields the same score for each subject (given that subjects have not changed). This reliability over time is known as ‘test–retest reliability’.

If we are assessing the merits of a test – as we well might in evaluating research reports, designing research or carrying out psychological testing in an educational, clinical or industrial setting – it is essential to ascertain whether a test is reliable. To do this it is necessary to know how reliability is measured and to be acquainted with the problems associated with such measurement.

Measuring internal consistency reliability

Split-half reliability The simplest measure of the internal consistency of a test is the split-half reliability. As the name suggests, half the test is correlated with the other half. The split can be by order of items – the first twenty with the last twenty or, in the case of ability tests in which the later, more difficult items may not be attempted by all subjects, odd items with even items.

Split-half reliability is a reasonably accurate measure of internal consistency, although how the test is split must obviously affect the results to some extent. A reliability coefficient of 0.7 or larger is necessary (for reasons to be discussed below) for a test to be considered satisfactorily consistent.

In evaluating split-half reliability coefficients two points must be noted, both concerning the samples from which the figures have been obtained.

1 Ideally, the reliability coefficients must be derived from samples similar to those on which the test is used or to be used. For example, if an anxiety test has a reliability of 0.8 with a normal population, there is no guarantee that such a figure will be accurate for psychiatric patients or criminal offenders. Separate coefficients should be quoted for different populations.

2 The sample from which the coefficient has been obtained should be sufficiently large to make the figures statistically reliable. In practice, this means minimum sample sizes of about 100 subjects.

The alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951) This is regarded by psychometrists (e.g. Nunnally, 1978) as the most efficient method of measuring the internal consistency of a test. In effect, coefficient alpha indicates the average intercorrelation between the test items and any set of items drawn from the same domain (i.e. items measuring the same variable). Coefficient alpha increases as the intercorrelations between the test items rise, a fact of some importance in evaluating the meaning of alpha reliability, as we discuss below in the section on the importance of internal consistency reliability.

KR20 reliability (Richardson and Kuder, 1939) This is a special form of the alpha coefficient adapted for use with dichotomous items. Since many personality inventories use such dichotomous items (of the yes/no or true/false variety), this index is frequently to be found in the study of personality tests.

These are the main methods used in the computation of internal consistency reliability. As was the case with split-half reliability, both the alpha coefficient and KR20 need to be derived from samples of adequate size and constitution.

Occasionally, two other methods of computing the internal consistency of a test can be found in the research literature.

The factor-analytic method If a test is factor analysed along with a variety of other tests, the square of its factor loadings can be shown (e.g. Guilford, 1956) to be its reliability. This is a powerful method of computing reliability. However, in evaluating this coefficient, it must be borne in mind that its actual value depends considerably on the particular tests with which a test has been factored and the technical adequacy of the factor analysis. Unless there are good grounds (and there rarely are) for arguing that there has been a proper sampling of test variables and of subjects, and that the factor analysis is sound, then any figures must be treated with caution.

Hoyt’s (1941) analysis of variance method In this approach test variance is broken down into two sources – item and subjects (together, of course, with their interaction). The smaller the variance due to items, the higher the reliability of the test.

The present author (Kline, 1971; Kline, 1980b), in developing three personality tests, Ai3Q, OOQ and OPQ, has found little practical difference in any of these indices. Generally, however, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is the most efficient, being independent of any particular split of the test.

The meaning and importance of internal consistency reliability

Psychometrists are eager to develop tests which are highly selfconsistent for the obvious reason that if part of a test is measuring a variable, then the other parts, if not consistent with it, cannot be measuring that same variable. Thus from this argument it would appear that for a test to be valid (i.e. for it to measure what it claims to measure), it must be consistent: hence the psychometric emphasis on internal consistency reliability. Indeed, the general psychometric view is exactly this, that high reliability is a prerequisite of reliability (e.g. Guilford, 1956; Nunnally, 1978). The only dissenting voice of any note is that of Cattell (e.g. Cattell and Kline, 1977). Cattell argues that high internal consistency is actually antithetical to validity on the grounds that any item must cover less ground or must be narrower than the criterion we are trying to measure. Thus if all items are highly consistent, they are also highly correlated, and hence a reliable test will measure only a narrow variable of little variance. As support for this argument it must be noted (a) that it is true that Cronbach’s alpha increases with the item intercorrelations and (b) that in any multivariate predictive study the maximum multiple correlation between tests and the criterion (in the case of tests, items and the total score) is obtained when the variables are uncorrelated. This is obviously so, in that if two variables were perfectly correlated, one would be providing no new information. Thus maximum validity, in Cattell’s argument, is obtained with test items that correlate not all with each other but each positively with the criterion. Such a test would have only low internal consistency reliability. Theoretically Cattell is correct in our view. However, to our knowledge no test constructor has managed to write items that, while correlating with the criterion, do not correlate with each other. Barrett and Kline (1982) have examined Cattell’s own personality test, the 16PF test fully discussed on p. 52, in which such an attempt has been made, though it appears not to be entirely successful.

In the case particularly of personality questionnaires, high reliability should be treated with caution, since by writing items that are virtually paraphrases of each other high coefficients can be obtained, but at the expense of validity. Despite these comments, generally the psychometric claim holds: in practice, valid tests are highly consistent.

Test–retest reliability

Measurement The measurement of test-retest reliability is simple. All that is required is the correlation of test scores on two occasions. To be useful, tests should have a test-retest reliability of at least 0.7. Concerning the necessity of higher test-retest reliability, for good psychological tests there is no dispute. However, a few points have to be watched in evaluating this aspect of a test.

1 As was the case with internal consistency reliability, the sampling must be sound (i.e. sample size should be not less than 100 subjects, and these should constitute a representative group).

2 The interval between testing sessions should be not less than a month, since a shorter interval than this may produce a spuriously inflated figure if subjects remember their previous responses.

3 To overcome this difficulty, some tests are constructed with parallel forms. In this case subjects take a different set of items on each occasion and test-retest reliability becomes parallel-form reliability. Where parallel forms of tests exist, there are considerable problems in demonstrating that the tests are properly parallel. Even if the correlation between the forms is high, this does not entirely meet the criterion of comparability, since to be truly parallel each equivalent item in the two tests should be shown to have the same response split in different populations and the same correlations with other scores. This is almost impossible to achieve. However, high parallel-form reliability probably permits the two tests to be interchanged in research with groups. For individual use, however, this writer is more sceptical.

4 Some good psychological tests can have low test-retest reliability if it can be argued that over time the variable is likely to have changed non-systematically among individuals, as is the case, for example, with measures of mood.

Generally, however, it is obvious that if tests are to be valid, they should yield the same score for individuals on any occasion; hence high test-retest reliability is a prerequisite of any sound test.

Test validity

The importance of reliability per se is small (other than for theoretical psychometrics): the emphasis on it arises from the fact that, as we have seen, high validity usually requires high reliability.

A test is said to be valid if it measures what it purports to measure. Such a definition is not as banal as it first appears, for two reasons: (a) the majority of tests, especially personality tests, are not valid, as even a brief perusal of the authoritative test reviews to be found in Buros’s Mental Measurement Yearbooks (e.g. Buros, 1978) will show; (b) the demonstration of validity, again particularly for personality tests, is exceedingly difficult.

There are logical problems in the demonstration of test validity that have to be understood if tests are to be properly used, especially for the construction of theory. These, however, are best explicated after we have scrutinized the different kinds of validity to be found in discussions of tests.

Types of validity

Face validity Face validity receives a mention only to be dismissed. A test is face-valid if it appears to measure what it claims to measure. Such an appearance can be quite misleading, and face validity is unrelated to true validity. It is important only because absurd tests, for example, may induce unco-operative attitudes in subjects taking them. Hence face validity is useful in establishing good rapport and co-operation. It is also important to realize that a personality questionnaire cannot be evaluated through an examination of the content of ...