![]()

1

THE TRADITIONAL ENTREPRENEURIAL FIRM

Until recently it would have been considered unusual to begin a book on organisational behaviour with a chapter on entrepreneur-ship. Traditionally, in management thinking, small businesses have been viewed as being of little importance in market economies largely dominated by large national and multinational corporations. In circumstances where such corporations can manipulate price levels, lobby governments and, both directly and indirectly, dictate market forces, the trading opportunities for small businesses would appear to be limited. Today, however, the attitude towards small businesses has changed.

In the conditions of the 1990s, small business and entrepreneurship are no longer seen as marginal to modern economies. Both government macroeconomic policies and corporate thinking now reflect small business values. Managers are encouraged to be entrepreneurial and to operate with structures which are flatter, with authority and responsibilities devolved to either cost or profit centres, business units and wholly-owned subsidiary companies. As such, corporate leaders are introducing organisational structures, cultures and operational practices which motivate managers to be more entrepreneurial in their day-to-day decision-making. They are trained to manage continuous change and are rewarded through performance-related results rather than through seniority-based promotion.

Opportunities for setting up profitable small business ventures are now greater than in the earlier post-war decades. Despite the growth of large corporations and their increasing market share, structural changes in modern economies are creating opportunities for small business growth (Dunne and Hughes, 1990). Corporate restructuring is bringing about an increasing emphasis upon subcontracting and out-sourcing. As large organisations slim to their core activities to compete within specific market niches, they are buying in products and services. These can range from personnel development to accountancy support, secretarial assistance, transport, catering, equipment, maintenance, and to the purchase of semi-finished components (Wood, 1989). Through these changes, corporations are attempting to become more flexible in their trading by relying more upon market rather than employment relations as the underlying basis of their work processes. These changes have implications for business start-up in both manufacturing and service sectors. Because of the fragmentation of corporate activities, there are growing opportunities for both management buy-outs and management buy-ins. Equally, corporate out-sourcing is creating market niches for small entrepreneurial ventures which, because of their low overheads, are able to deliver, on a profitable basis, specialist goods and services. These trading arrangements offer continuing opportunities for business start-up and these trends have been reinforced by changes in the market place. The growth in affluence has created market niches for a wide range of personalised quality goods and services. Through patterns of personal expenditure, there is a growing tendency for consumers to express their individuality and differences in lifestyles. This provides a range of business opportunities for entrepreneurs able to meet specialist needs. Small business proprietors can carve out market niches in which they are able to trade profitably and, because of the personalised nature of the products and services, they can erect boundaries which restrict entry by larger competitors.

Such developments are part of broader socio-economic trends. Increasing affluence has led to greater purchasing of commodities and services associated with home maintenance, recreation and leisure, sport, physical fitness and various professional services. However, while some are small business proprietors for most of their working lives, others will engage in such activity for more limited periods. After pursuing careers in large corporations, or as a personal strategy to avoid unemployment, business start-up offers potentially attractive rewards. Accordingly, entrepreneurship is now more important than in the past, while equally, many medium-sized enterprises stem from very small-scale entrepreneurial origins.

WHY DO PEOPLE START THEIR OWN BUSINESSES?

The prime motive for business start-up is often viewed to be associated with financial reward. However, there are a range of factors, many of which stem from personal needs for independence and self-fulfilment. Many men and women choose to start their own businesses to escape from the controls, rules and regulations which are found in any employment relationship. They resent being told what to do by immediate bosses and object to their work patterns being regulated by organisational procedures. Business proprietors, despite their long working hours, the competitive threat of market forces, and the demands of their customers, can enjoy a greater degree of personal control in their relationships with others. Women in particular are attracted to entrepreneurship in the United States and Britain for this reason. Because of the nature of corporate cultures, career structures and managerial practices which often restrict their career advancement within various organisational settings, they stand to enjoy greater personal success and psychological autonomy through starting their own ventures. Equally, members of ethnic minorities can avoid prejudice and restricted career routes through business start-up.

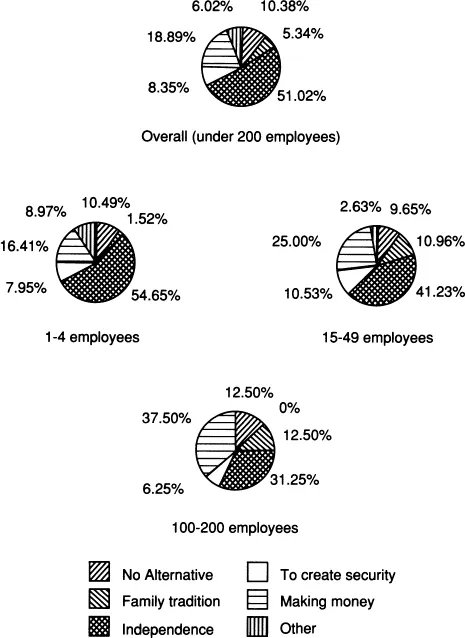

The personal motives for business start-up will inevitably be a function of a variety of factors, of which psychological influences will play some role (See Figure 1.1). However, it has proven difficult to identify any particular characteristics of personality among those who start their own businesses (Chell, 1986). Social psychologists have searched for patterns, but their conclusions are contradictory and inconclusive. They tend to stress how, compared with others, entrepreneurs are more prone to take risks, to be innovative, and to search for personal autonomy in their working lives. However, such characteristics are ill-defined and insufficiently supported by scientific evidence (Kets de Vries, 1977). All that can be said about those who start their own businesses is that they are more able than others to work independently and to pursue their own economic self-interest without the need for the structure and support systems found in large organisations. In this sense, they tend to be ‘inner-directed’ rather than ‘outer-directed’ in their patterns of behaviour (Trompenaars, 1993). They have the confidence to establish a sense of self-esteem which is independent of others’ opinions. This ‘inner locus of control’ leads them to feel personally responsible for their own actions. This is in sharp contrast to others who are more inclined to develop social networks which are then significant in shaping feelings of self-respect. Entrepreneurs obtain self-esteem through their businesses, and accordingly the opinions of others are of limited importance. Interviews with those who have started their own businesses reveal a broad range of motives, attitudes and behaviour.

Figure 1.1 Motivations of small business proprietors in the United Kingdom by size of firm

Source: Nat West Quarterly Survey of Small Businesses (QSSB), Vol. 6, No. 2, 1990

Motives for business start-up: some survey results

There Is no clearly identifiable pattern. The motives for starting businesses are remarkably diverse among entrepreneurs. In the interviews there was a discrepancy between general notions about who starts, businesses and the detailed accounts of their own personal histories. Although many subscribe to conventional notions about ‘self-made’ people, a totally different set of interpretations emerges in accounts of their own and other people’s concrete experiences.

In our general conversations about the psychology of the business-owner, the same essential qualities are repeatedly emphasised. The owner-director of a company with 50 employees, for example, stressed the ability to ‘… wrestle with any problem that comes along and to sort it out and to never give up. There’s a certain will and determination to see the thing through – and to fight it all the way.’ This is coupled with the qualities of drive and ambition. One of the small employers claimed that,

You’ve got to be a bit more ambitious than your immediate counterparts. For a worker to set up on his own he has got to have a little more ambition than the worker on either side of him who’s quite happy to plod. The most important quality that I’ve had to call upon myself has been my resilience and my determination. I think that just about covers everything for me. My determination makes me work hard when I’m tired. My resilience helps me to recover when I’ve had a terrible shock, when things have gone wrong.

But there was one further necessary quality – independence. This quality was strongly emphasised by an owner-director who argued that starting a business,

… attracts people who want to be their own boss, and for that reason often go ahead, and who have got a fair amount of initiative and who like to be independent. You don’t get what I call the ‘safety-first’ type of chap, who goes into public service. It does tend to attract the type of chap who’s got what I call sturdy independence.

But still these assumed psychological qualities do not complete the picture. Further capacities are emphasised; more specifically, reserves of energy and enthusiasm are regarded as particularly important. According to an owner-director, with an annual turnover of £6 million, ‘It’s got a lot to do with the amount of energy one’s prepared to put into it. You put energy in the right direction and I think that the results are there.’

The motivation underlying the hard work and the risk that the ‘self-made’ man is prepared to take is seen by many as monetary gain. Comments emphasising the cash rewards of entrepreneurial risk were repeated many times, one of the more explicit being put forward by the owner of a company with a £100,000 turnover. He stated, ‘I always think I’m going to make a fortune, and the day I stop thinking about it, I shall be lost.’

Personal satisfaction is acquired through developing a business rather than by enjoying a high personal standard of living. This is the picture of the business proprietor as conveyed by the interviews and it contains few surprises. He is seen to be hard working, ambitious, energetic and motivated by economic gain. This image has persisted over the decades, despite the dramatic changes which have occurred both within the economy and in the nature of business enterprises. Yet the whole picture is distorted by two fundamental flaws. First, ambitious, hard-working and energetic people are to be found in all walks of life and not solely among business proprietors. These notions, then, do not enable us to identify a distinguishable entrepreneurial type. Secondly, the image ignores a number of other important factors which are crucial in accounting for the concrete experiences of the people we interviewed.

When we turned from asking questions about the necessary personal qualities needed for business success in general to specific accounts of how they actually started their own enterprises, very different explanations were put forward. These were factual accounts within which there was no place for ‘conventional wisdom’ and received, everyday rhetoric. Analysis of these accounts indicates that many proprietors are motivated by a wide range of social and non-economic factors of the sort that are often neglected in general discussions of entrepreneurial types. Thus, business formation and growth is often not the outcome of exceptional personal capacities of drive, determination and ambition but a function of various forms of personal discontent and random occurrence. Hence, for many of the people we interviewed, the reason for starting a business was not out of a desire ultimately to become a successful entrepreneur, but a rejection of working for somebody else. In rejecting the employee role, two major factors are emphasised – authority and the wage/profit relationship. For some, starting a business represents an escape from the control of others. As an owner with a turnover of £250,000 told us, ‘I’m one of those people who find it very difficult to work under other people if I’m truthful. It’s not something I do very well, put it that way. And that, amongst other things, is what made me start on my own.’ Similarly, a self-employed man recalled, ‘I was sort of an independent nature. Although I always got on alright working for people I was never particularly happy when I wasn’t in charge of my own destiny.’

But there were others who felt that, as employees, they were being exploited. As one respondent recalled, ‘I decided I was fed up with other people getting the money that I was really earning for them. They were all running about in fast cars and I was getting nothing.’ If starting a business enables a person to escape from the constraints of authority, the wage/profit relationship and other features of being an employee, it also allows him or her to ‘do a good job’. This was a factor in another respondents decision to ‘go it alone’. ‘I got fed up with being told how to do things which I knew were wrong. I had the manual skill and the technical ability to go on my own. That’s the only way you can do what you want to do – to be on your own.’ This statement was confirmed by a small employer who said, ‘When I’m doing a job it’s my decision and freedom as to whether I do it one way or another. Rather than worry about what some other chap wants me to do.’ As employees, these men had felt they were unable to exercise their skills and they ‘opted out’ in order to produce good quality work. Such sentiments often persist long after the formation of a business. Although many of the people that we interviewed were motivated by economic gain, this was often bounded by the desire to produce ‘a good job’, ‘something that is useful’, ‘something that the customer will be pleased with’.

These various examples do not deny that many businesses are set up with determinedly money-making motives but they do challenge the notion that every aspiring ‘self-made’ man glows with entrepreneurial fervour. It seems to us that the conventional view of the entrepreneurial type has serious shortcomings. It gives insufficient attention to the highly variable non-monetary factors that are often central to the formation of business enterprises and it imposes ‘rational’ and ‘logical’ explanations upon experiences and behaviour that are extremely diverse, personal and random. It is virtually impossible to predict those who will become entrepreneurs, business proprietors and ‘self-made’ men and yet the conventional wisdom persists.

Source: Scase and Goffee (1987a, pp. 29–37)

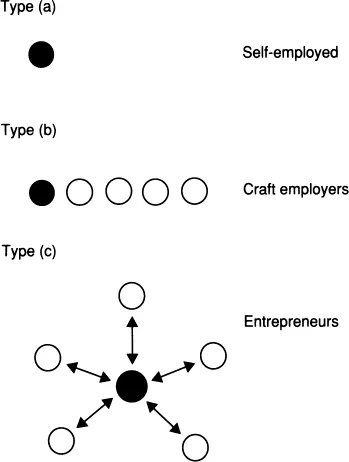

The motives underlying business start-up have important ramifications for the nature of business growth, their marketing strategies and their general style of management. It is too simplistic to collapse a diversity of proprietorial and managerial styles into a single generic category of ‘small business’ (Goss, 1991). The characteristics of skill, product and market are also important determining factors shaping significantly features of the management process within these firms. ‘Low-skill’, ‘manual’ or ‘craft’ enterprises will be organised rather differently from those providing professional services, or producing high-quality technological and scientific products. The rest of this chapter discusses the managerial characteristics of these traditional entrepreneurial firms; namely ‘low-skill’ and craft businesses (see Figure 1.2), while the next will consider the features of enterprises established on the basis of professional, technical and creative competences.

ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND MANAGEMENT STYLE

It is possible to differentiate small businesses according to the work and/or managerial roles of their proprietors. It is necessary to consider these before analysing the overall managerial issues of manual craft businesses in general.

Type (a): the self-employed

For many, self-employment is the ultimate goal of business proprietorship. Essentially, the self-employed undertake all tasks. They may make use of unpaid family labour or, at best, others on a part-time basis, but they employ no staff on a regular basis. Such businesses are usually set up on the basis of specific craft skills which are then used for the purposes of trading in a particular local market niche. These are the carpenters, plumbers, hairdressers, electricians, window cleaners, secretaries, car mechanics, and many others who sell to customers their personal skills of one kind or another. It is their detailed knowledge of trading opportunities within a particular locality that often motivates craft workers to start on their own. Their enterprises are based upon the delivery of goods and services to customers on a regular and personal basis. In this way, they have immediate feedback from the market in terms of response both to the quality of their services and to the prices which they charge. Such traditional traders, however, often lack basic business management skills, since their overriding goal is to provide services to customers on the basis of their craft skills. For this reason they may under-charge, confuse turnover with profits, have high but hidden overheads and generally neglect the book-keeping and general administration of the business. It is weaknesses in these areas that lead to their high failure rates, particularly during recession as in the 1990s, rather than deterioration in the quality of services or products.

Figure 1.2 The contrasting roles of traditional entrepreneurs

Self-employed enterprises often have precarious futures because they are entirely dependent upon the talents and energies of their proprietors, a feature which is reinforced by their reluctance to employ others. The latter is a function of their lack of management skills and training and also because of their underlying motive for business start-up – the need for per...