eBook - ePub

Budget Deficits and Economic Performance (Routledge Revivals)

- 226 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Budget Deficits and Economic Performance (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

At the time in which this book was first published in 1992, there was a major concern with the macro-economic implications of fiscal imbalance. As the European economies moved closer to monetary union, and Germany grappled with the fiscal pressures of unification, deficits in the United States exceeded $300 billion. In this volume the authors address this issue, using both historical case-studies and cross-national comparisons. This book will be of interest to students of economics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Budget Deficits and Economic Performance (Routledge Revivals) by Richard Burdekin,Farrokh Langdana in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Budget deficit financing: a general review

Let us begin by examining the temporal, or dynamic, budget constraint within which the fiscal authority is obliged to limit its expenditure in any given time-period. This will give us a better understanding of the economic intuition linking fiscal policy, monetary policy, and central bank independence.

The dynamic government budget constraint is:

where Pt is the current price level, Gt and Tt are real levels of government spending and tax revenues, respectively, Dt is government debt issuance in the form of short-term discounted government bonds, and Mt is money creation in the current period.

Expression 1 states that the current nominal budget deficit, Pt(Gt – Tt), and the debt service on government bonds issued in the previous period, Dt−1 are financed partly by the issuance of government debt through the treasury, Dt, and partly by monetization Mt by the monetary authority.1 Therefore, an independent central bank that announces and maintains a fixed time-path of money creation (Mt), irrespective of the deficit financing needs of the fiscal authority, Pt(Gt – Tt) + Dt−1 could restrain the ability of the government to incur future unrestricted budget deficits. Knowledge that the central bank will only monetize a fixed fraction of the deficit, together with the fact that domestic and foreign individuals will absorb only a finite amount of government debt, can in principle impose fiscal discipline on a deficit-incurring administration. Therefore, fiscal policy might be less profligate and more restrained in countries with more independent central banks. This reverse causality – from central bank autonomy to fiscal policy – is the particular focus of the research presented in Chapter 7.

Conversely, an economy in which the central bank readily accommodates fiscal borrowing by monetizing the outstanding government debt is more likely to see deficit-spending pressures chanelled directly into rampant inflation. A case study of the extreme consequences that may follow from this process is provided in the next chapter, in which we analyse the German hyperinflation of 1919–23 from a fiscal perspective.

We can extend the budget constraint to include the foreign sector in the dynamics of government borrowing. The government bond sales Bt in (1) are comprised of Treasury bond purchases by domestic as well as foreign investors; our next task is to incorporate these international effects, and discuss one mechanism linking forign capital flows and trade deficits to budget deficits that are primarily bond-financed. This is accomplished using the national savings identity:2

where G and T are as defined earlier, S and I are private savings and investments, and F and X are real values of imports and exports, respectively. The term (G – T) is the budget deficit (surplus, if negative), which must be financed by net private domestic saving, (S – I), plus the current account deficit, (F – X).

The economic intuition here is that the left-hand side of the above identity constitutes a demand for loanable funds on the part of the fiscal authority to finance the deficit through issuing bonds, while the two expressions on the right are a ‘source’, or supply, of loanable funds.

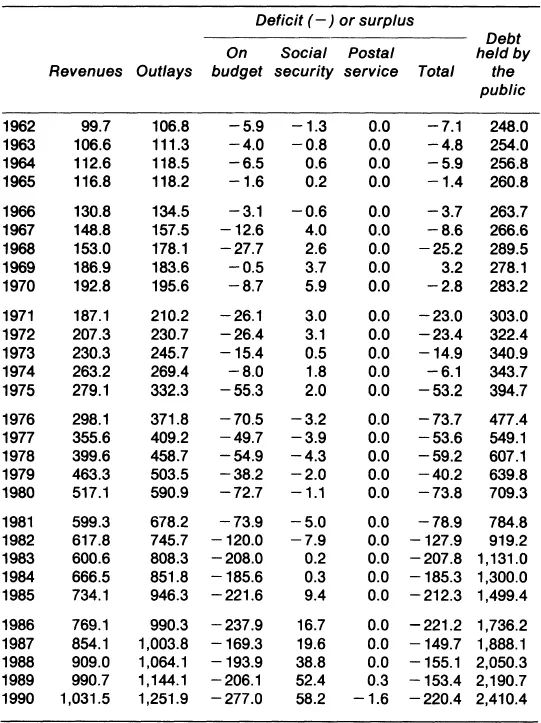

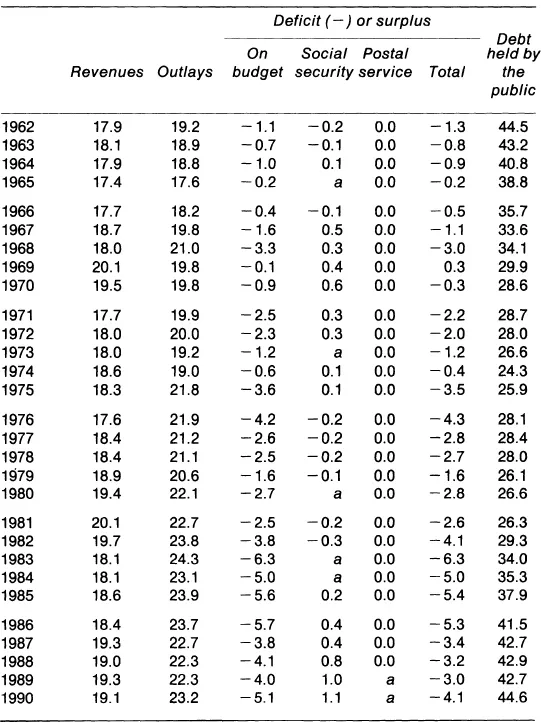

Before turning to an explanation of why the current account deficit constitutes a supply of loanable funds, a discussion of the mechanism linking the federal budget deficit (G – T) to the nation’s current account deficit (F – X) is necessary. Increases in government borrowing (see Tables 1 and 2) in the absence of accommodative monetary policy (such as those experienced by the US in the early 1980s) result in domestic real interest rates exceeding those of the other industrialized countries. As domestic and foreign investors shift out of foreign assets into the higher-yielding domestic asssets, they sell foreign currency for domestic currency, putting upward pressure on the domestic currency in the foreign exchange markets and bidding up nominal exchange rates.

In the US case, as American government borrowing continued unabated, the US dollar became progressively stronger, reaching unprecedented strength in 1984–5. The domestic currency appreciated in both nominal and real terms, spurring the demand for ‘cheaper’ imports, weakening the foreign demand for the now more ‘expensive’ US exports, and thereby helping to explain the simultaneous increase in both the current account deficit and the domestic budget deficit. Moreover, as the deficit-incurring country’s current account worsens, this results in an increase in dollar-denominated deposits in the reserves of central banks located in countries incurring trade surpluses. These deposits, in turn, can be expected to manifest themselves as capital inflows of the type experienced by the US from Japan for most of the 1980s – which supplemented domestic savings, and helped partly to finance the deficit.

The pertinent question then, is under what conditions could the fiscal authority perpetually exploit the national savings identity presented above, by continuously issuing government debt to domestic and foreign investors? This lies at the heart of the issue of the ‘sustainability’ of bond-financed deficits – the ability to continuously roll-over government debt by issuing new bonds, without the necessity of any monetary accommodation and its accompanying inflation.

Seminal work by Sargent and Wallace (1981) indicates that when the fiscal policy ‘dominates’ monetary policy by independently pursuing a time-path of budget deficits, and when the real rate of interest payable on bonds exceeds the growth rate of the economy, monetary accommodation is inevitable.3 Later, Hamilton and Flavin (1986) examined data from 1962 to 1984 and used the intertemporal budget constraint (1) to determine if the deficit time-path was stationary. Other studies of sustainability include Barro (1979), McCallum (1984), Trehan and Walsh (1988), Kremers (1988, 1989), Joines (1991), and Hakkio and Rush (1991), to cite a few. While these papers differ in their methods of defining and measuring sustainability, they find strong evidence supporting the premise that government behaviour is indeed consistent with the intertemporal budget constraint discussed above.

With this review of the intertemporal budget constraint, the national savings identity, the dynamics of deficit finance, and armed with an intuitive meaning of the term ‘sustainability’ of deficits, let us now turn to the detailed analysis offered in the following chapters.

Table 1.1: Revenues, outlays, deficits, and debt held by the public, fiscal years 1962–90 (in billions of dollars)

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Table 1.2: Revenues, outlays, deficits, and debt held by the public, fiscal years 1962–90 (as a percentage of GNP)

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Note: a Less than 0.05 per cent.

Note: a Less than 0.05 per cent.

Chapter 2

The role of fiscal policies in the German hyperinflation: how unpleasant was the monetary arithmetic?*

INTRODUCTION

Any review of the current status of European economic integration must take into account how, by pegging their exchange rates to the Deutschmark under the Exchange Rate Mechanism of the European Monetary System, the EC countries have seemingly imported the tight monetary policies of the Bundesbank. Indeed, it is often argued that the decline in the average inflation rates of the EC member countries can be attributed to lower long-term inflationary expectations stemming from the historic monetary and fiscal discipline of the Germans (see, for example, Giavazzi and Giovannini, 1989, Chapter 5). In spite of the pressures recently experienced by the Bundesbank in the face of the large fiscal outlays stemming from German unification, the anti-inflationary emphasis still remains very much in evidence.

However, in the midst of the widespread economic research concerning the current role of Germany in the European (and world) economy, one should not lose sight of the question of how and why this German monetary discipline has come about. The answer to this may well lie in the macro-economic trauma experienced by the Germans during the hyperinflation period of 1919–23. A thorough understanding of these historical developments is helpful, both in terms of appreciating the background to the subsequent policy stance of the Bundesbank, and as a valuable illustration of the extreme pressures placed on ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword by Thomas D. Willett

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Notes

- References

- Index