![]()

CHAPTER ONE

To Elevate Materialism: Hunt’s Search For a New Iconography

WILLIAM HOLMAN HUNT characteristically based his conceptions of realism and painterly symbolism upon his religious belief. As he explained to William Bell Scott, he had arrived at his conclusions only after careful

consideration of the two views (religion or no religion) on life. What is the reason of the dead-alive poetry and art of the day, if not in the totally material nature of the views cultivated in modern schools? Trying to limit speculation within the bounds of sense only must produce poor sculpture, feeble painting, dilettante poetry.1

He believed that without faith, art becomes materialistic, empty, literal, and dead, because such unspiritualized art can only present facts for their own sake. This dread of meaningless fact explains how Hunt, who painted in such a supposedly realistic style, could emphasize in Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood that he and Millais always thought art had to express feelings and thus could never be 'the icy double of facts themselves'. He emphasizes 'we were never realists', for he and Millais — much less Rossetti — were never interested in making 'a representation, elaborate or unelaborate, of a fact in nature' for its own sake, because to do so would destroy the imagination, that 'faculty' which makes man 'like a God'. According to Hunt, 'a mere imitator', who does not make use of his imagination, necessarily 'comes to see nature claylike and finite, as it seems when illness brings a cloud before the eyes' (I.150).

Thus Hunt was fighting two different, though related battles: on one front he fought to popularize a realistic style of painting that could more effectively render both secular and scriptural subjects; on the other, he struggled to find a means of keeping that carefully represented accumulation of facts from becoming a mere scientific record. By 1856 one part of the struggle, the easiest, had clearly been won, for by then 'many followers were admired chiefly for mechanical skill, and in some cases this was of a very complete kind, although wanting in imaginative strain. An increasing number of the public approved our methods, perhaps the more readily when no poetic fancy complicated the claim made by the works' (II.89). The reviewers agreed, for as the Art-Journal put it a few years later, 'the precisians are "masters of the situation"'.2 But Hunt's concomitant aim of spiritualizing art never met with the same success, and, indeed, one suspects that many of his Victorian contemporaries never realized he had this second goal in mind.

One means of preventing his art from presenting nature 'claylike and finite' was to depict emotionally powerful scenes from literature and from sacred or secular history. From his earliest paintings Hunt sought to capture the drama intrinsic to climactic moments — whether conceived as theatrical scenes of encounter and recognition or those in which true spiritual illumination occurs. Thus, whereas Rienzi, The Awakening Conscience, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, and even The Lady of Shalott (Plates 12, 10, 4, 30) portray such powerful moments of illumination or conversion, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus and Claudio and Isabella (Plate 11) depict more conventionally theatrical subjects. A second, less accessible, means of surmounting the problems of visual realism was to present landscapes and events that were charged with imaginative power, and his entire program of recording scenes in the Middle East exemplifies this part of his enterprise. A third, more complex means was to employ elaborate forms of symbolism, or as a contemporary critic put it in a phrase already quoted: 'The attempt . . . is to elevate materialism by mysticism, and to make even the accessories of an inanimate realism instinct with spiritual symbolism.'3

Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood relates that when he was at work on the Christ and the Two Marys (Plate 13) in 1847, he had tried to find a symbolical language to replace that of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. He had complained to Millais of his difficulties, pointing out that the 'language' of the earlier masters 'was then a living one, now it is dead', and therefore to repeat either their iconography or compositions 'for subjects of sacred or historic import is mere affectation'. He went on to explain to his friend that in his picture of the risen Lord, earlier artists would have put 'a flag in His hands to represent His victory over Death: their public had been taught that this adjunct was a part of the alphabet of their faith'. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, that language of faith, like the faith itself, had largely disappeared; and although the 'artgalvanising revivalists' would certainly approve of his making use of such an older, once hallowed convention, such painterly symbolism would be little more than a self-conscious use of the conventions of a past age. In contrast, Hunt wanted a symbolism that could speak to the nineteenth century (I.84-5).

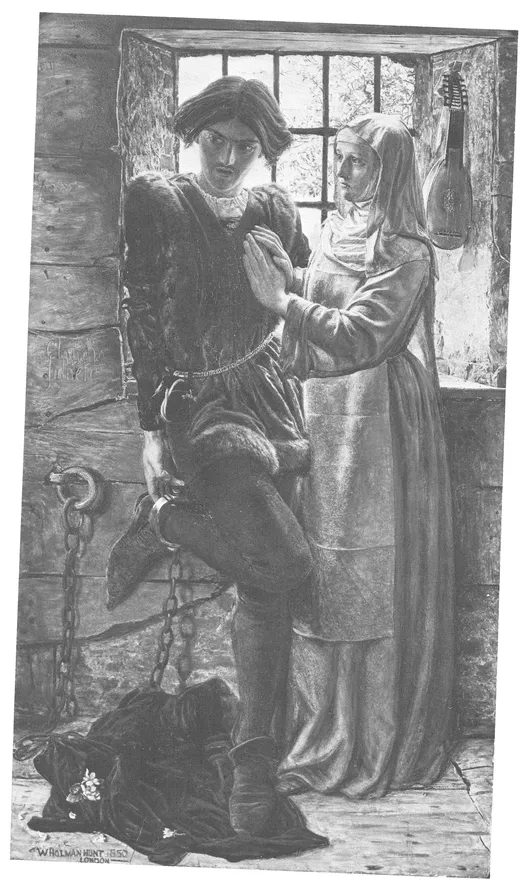

11. Claudio and Isabella. 1850-3. Tate Gallery, London.

This intense concern with the role of symbolism in art, particularly in any art which speaks to a wide audience, would help to explain his choice of Rienzi (Plate 12) as his first Pre-Raphaelite work. This picture, which he based on Buiwer-Lytton's novel, embodies two subjects which had long interested him, a moment of conversion and the appearance of a saviour. Another factor which might have attracted the young painter to the hero of Bulwer-Lytton's novel is that when Rienzi arouses the Roman people to revolution, he chooses an elaborately symbolic painting displayed in a public square as his first weapon. Chapter IX of the novel — 'When the people saw this picture, everyone marvelled' — describes how the spectators stood fascinated but puzzled before the picture until one of Rienzi's followers, Pandulfo di Guido, 'a quiet, wealthy, and honest man of letters', stepped forth to explain it to them:

You see before you in the picture . . . a mighty and tempestuous sea: upon its waves you behold five ships; four of them are already wrecks, — their masts are broken, the waves are dashing through the rent planks, they are past all aid and hope: on each of these ships lies the corpse of a woman. See you not, in the wan face and livid limbs, how faithfully the limner hath painted the hues and loathsomeness of death? Below each of these ships is a word that applies the metaphor to truth. Yonder, you see the name of Carthage; the other three are Troy, Jerusalem, and Babylon. To these four is one common inscription: 'To exhaustion were we brought by injustice!' Turn now your eyes to the middle of the sea; there you behold the fifth ship, tossed amidst the waves, her mast broken, her rudder gone, her sails shivered, but not yet a wreck like the rest, though she soon may be. On her deck kneels a female, clothed in mourning . . . she stretches out her arms in prayer, she implores your and Heaven's assistance. Mark now the superscription: 'This is Rome!' Yes, it is your country that addresses you in this emblem!

Having captured the attention of the crowd, Pandulfo di Guido then explains that the storm which threatens to destroy the Roman ship of state issues forth from the mouths of four groups of allegorical beasts. The lions, wolves, and bears, he tells the crowd, represent the 'lawless and savage signors of the state', while the dogs and swine are the 'evil counsellors and parasites . . . Thirdly, you behold the dragons and the foxes; and these are false judges and notaries, and they who sell justice. Fourthly, in the hares, the goats, the apes, that assist in creating the storm, you perceive, by the inscription, the emblems of the popular thieves and homicides, ravishers, and spoliators.' Pointing out that the picture offers hope of redemption, hope that the ship will yet save herself, the orator emphasizes that above the angry sea the heavens open and God descends 'as to judgment: and, from the rays that surround the spirit of God extend two flaming swords, and on those swords stand, in wrath, but in deliverance, the two patron saints — the two mighty guardians of your city!'4 Such, then, was Rienzi's successful call to revolution, his picture that 'speaks' and speaking awakens the people to defend themselves against tyranny. One can understand Hunt's attraction to Bulwer-Lytton's novel even without drawing upon this particular scene, nonetheless, the young painter's fascination with the role of symbolism in public art makes it seem likely that the Tribune's use of such a painting had great appeal for him. In particular, the picture which Pandulfo di Guido interpreted for the crowd exemplifies the kind of art capable of speaking to all men, learned and unlearned alike.

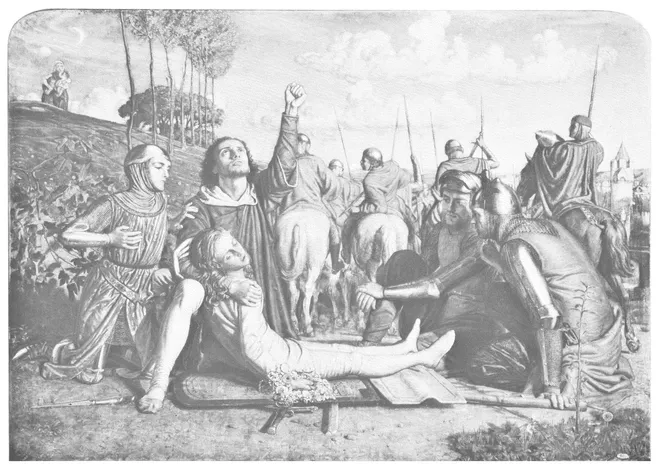

12. Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions. 1848-9. Collection Mrs. E. M. Clarke.

In his memoirs Hunt explained how important the example of Shakespeare had been to him, for when he first began to read his works as a boy, he found himself

13. Christ and the Two Marys [The Risen Christ with the Two Marys in the Garden of Joseph of Aramathea]. 1847-c. 1900. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

astonished at the condescension of his mind . . . As a dramatic teacher he did not despise the groundlings; indeed I concluded that the great measure of welcome awarded to this kingly genius was but a just reponse to his own large-hearted sympathy with his fellows of every class; he catered for the unlearned not less than for the profoundest philosopher.

The example of the great dramatist, he explains, also led him while yet a young man 'to rate lightly that kind of art devised only for the initiated, and to suspect all philosophies which assume that the vulgar are to be left for ever unredeemed' (I.148). Immediately after emphasizing his own belief in the need for art to be accessible to all men, Hunt gently criticizes Rossetti for abstracting himself from contemporary affairs and, one may assume, from the needs of most men and women. From this vantage point, we may observe that, in Rienzi, this art-propaganda which successfully calls for revolution plays a role opposite to that of Chiaro dell'Erma's fresco in Rossetti's 'Hand and Soul'. It is not that Hunt sees the artist fanning the passions which lead to war and revolt, while Rossetti believes him incapable of calming those passions to produce peace. Rather when Rossetti's protagonist finds his mural of Peace splattered with the blood of rival factions, he turns, as did Rossetti himself, to a private symbolism. Believing that art cannot succeed at grandiose public enterprise, he chooses to be true to himself and concentrate upon a more intimate —if more limited — goal. In this work, written about the time that Hunt encountered Bulwer-Lytton's novel, Rossetti, the son of an exiled Italian revolutionary, seems to have responded to a conception of art that Hunt would espouse, denying its applicability to him.

Nonetheless, even assuming that Hunt was drawn to this scene in Rienzi, he could find it only an inspiring example. Rooted in the trecento, this fictional painting could not be a model for him to emulate except in the most general terms. In fact, the example of this symbolical painting, like that of earlier religious art, merely emphasized for Hunt how much the nineteenth century had lost, how much it had to regain. Similarly, the works of the Early Netherlandish school he and Rossetti saw during their pilgrimage to the continent in 1849 — and the graphic work of Dürer and others which he studied in the Print Room of the British Museum — only served to make him yearn for new solutions to the problem of creating an iconography suited to the needs of his Victorian audience.

Hunt's greatest difficulty, as he was the first to recognize, was that older forms of symbolism and the conceptions of art which had generated them had become outmoded and dead. They were merely another set of conventions which had to be replaced if he were to create a living art. Victorian writings on both art and literature demonstrate that the basic attitudes necessary to a living allegorical art had long vanished, for the changing attitudes toward external reality which led to the rise of realism destroyed the relevance of symbolism for most critics and painters. Once men began to accept that reality, the Real, inhered in the visible, the here and now, older notions that some higher realm possessed a greater reality quickly lost force and eventually all but vanished. Equally important, English romantic criticism of the arts and literature regarded allegory as an intellectualized, artificial, unimaginative form of thought, something destructive of great poetry and great painting. Thus, Coleridge, Macaulay, and Arnold all agreed that, whereas a symbol is a product of the imagination, allegory arises in the intellect and leads to an artificial, unimaginative poetry.5 Contemporary writers on the arts generally took a similar position, attacking Victorian attempts at pictorial allegory as artificial, ineffective, and incomprehensible. The Art-Journal, for example, almost always derided any attempt to employ allegory or symbolism — it didn't distinguish between the two — and one rare exception occurred when its foreign contributor defended Wilhelm Schadow's The Fount of Li...

![13. Christ and the Two Marys [The Risen Christ with the Two Marys in the Garden of Joseph of Aramathea]. 1847-c. 1900. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1642841/images/fig00014-plgo-compressed.webp)