eBook - ePub

Popular Cinema and Politics in South India

The Films of MGR and Rajinikanth

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This work breaks new ground in the understanding of South Indian cinema and politics. Through incisive analysis and original concepts it illustrates the private, public and cinematic personas of MGR and Rajinikanth. It challenges the popular and scholarly myths surrounding them and shows the constant negotiation of their on-screen and off-screen identities. The book revisits the entire political history of post-Independent Tamil Nadu through its cinema, and presents a refreshing psycho-political and cultural map of contemporary South India.

This absorbing volume will be an important read for scholars, teachers and students of film studies, culture and media studies, and politics, especially those interested in South India.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Popular Cinema and Politics in South India by S. Rajanayagam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ASSEMBLAGE STRUCTURE

The Indian commercial film — any Indian feature film for that matter — has as its core the structure of the ‘universal’ classical drama, while sporting at the same time a unique, culture-specific structure of its own, a fact that makes it difficult for a Westerner, not familiar with the national cultures in the Indian subcontinent, to comprehend and appreciate this peculiar narrative layout.

Classical Core

To begin with, a typical classical drama starts with protasis (exposition), followed by epitasis (complication) and catastasis (new and further element of complication), reaching catastrophe (resolution), and is wound up with epilogue. The catastrophe consists of peripeteia (reversal of fortune or conversio) and anagnorisis (transition from ignorance to knowledge or cognitio). Epitasis and catastasis are achieved by creatively combining elements of suspense and surprise with narrative knots and twists.

This traditional linear structure of conflict–development–climax–denouement model1 is ‘inculturated’ into the Indian screen by incorporating elements of the grand kaavya literature and folk cultural kooththu performance. While the main story moves forward vertically in different storylines, it is interspersed with horizontally laid out branch stories, and ‘non-story’ components such as song-and-dance inserts, parallel comedy tracks and stunt sequences. When these ‘stories’, ‘storylines’, and the ‘non-story’ components of a film are woven together, the resultant narrative has the structure of a more or less coherently laid out ‘assemblage’, and the whole film in effect becomes a spectacular feast of nava rasas.2 Thus, in contrast to the single-genred Western film, each Indian film (including many of the so-called ‘new wave’ ones) is an innovative admixture of a wide range of genres.

Popular stars like MGR and Sivaji of the past, and RK, Kamal, Vijayakanth, Vijay, and Vishal of the present, adroitly exploit these ‘assembled’ elements to establish their respective screen images.

Forms from Culture

Kaavya, meaning epic, has a well-knit grand narrative structure, subsuming innumerable little narratives as ‘branches’, which are employed either as illustrative examples or as biographies of related characters. Kaavya is essentially hero-centric, and the characters are assigned values vis-à-vis their bond(age) to the hero. The inherent ideology is status-quoist, and the overall tone is characterised by grandeur, beauty and ethics. All these aspects of kaavya are applicable to film as well. In fact, these aspects form the very backbone of the deep narrative structure of the films starring popular heroes.

Kooththu, meaning ‘play’ in rural parlance, has, as opposed to kaavya, a loosely-knit narrative structure, replete with folk songs, dances, stunts and double entrendres. Kooththu is performed as an inseparable part of the annual village festival (oor thiruvizhaa) in honour of the village deity, for the twin-purpose of entertaining and giving a socio-religious message. Such a festive context also provides kooththu performance with certain ‘liminal freedom’, which manifests itself as social criticism, mainly through the character of the ‘buffoon’, who plays a variety of roles including that of a jester and a commentator.

Kooththu, which is characterised, therefore, by religiosity, entertainment and social criticism, often has as its contents the quasi-historical and semi-mythological folk heroes and heroines. Sometimes, the folk derivatives of the branch stories from kaavya also constitute the contents of kooththu.3 Film as a mass medium appropriates these features of kooththu, empties them of their radical and subversive potential, if any, and incorporates them with its kaavya core. Thus, film in effect is a kaavya performed as a kooththu.

It may be pertinent here to note that during the early years of cinema the elite sections of society viewed the film artistes with condescension, if not always with contempt. Even at a time when cinema held a complete sway over the masses, the elite and the Congressmen perceived cinema as a mere picturised version of kooththu. Noted Congress leader Kamaraj, one of the former chief ministers of Thamizh Nadu, referred to the then DMK front-rung leaders including Anna, M. Karunanidhi and MGR as kooththaadikal (literally, performers of kooththu) because of their links with the cinema industry.4

Contents from Culture

If the structure of the commercial film is an assemblage of kaavya and kooththu, when it comes to the contents, it is not rare to find specific motifs, themes, and even plots5 drawn from three divergent cultural sources: the pan-Indian kaavyas and puranas, the region-specific kooththu folktales and myths of oral traditions, and the corpus of Thamizh classical literature starting from the Sangam age. The use, however, is very subtle and the motifs are re-enunciated metaphorically or metonymically within the universe of contemporary discourse.

The frequently recurring archetypal characters in Thamizh films include: Rama–Sita (ideal husband-wife relationship), Kovalan–Mathavi (extramarital sex), Kannahi (‘queen of chastity’), Surpanaka (falling in love with another’s husband), Draupadi (polyandry), Pandavas versus Kauravas (feud between in-laws), Rama–Ravana (good versus evil), Krishna–Gopis (‘lila,’ the play; by extension, eve-teasing), Lakshman (ideal brother), Karnan (ideal friend), Saguni (the schemer), Kunthi (virgin mother; by extension, one who gives birth through premarital sex), Murugan–Valli–Theivanai (‘legal’ bigamy), Nallathangaal (folk version of pieta, the suffering mother), Mathurai Veeran (folk hero from an untouchable community), King Manu (symbol of justice), Thiruvalluvar (the Great Intellectual), Avvaiyaar (the Wise Old Lady), and munificent nobles and chieftains like Paari.

The popular or commercial films, therefore, serve as a synthesis of dominant and subaltern cultures both in form and in content.

Double Climax

Since a film is screened in the movie houses in India as two halves to make provision for interval — a short break for about 15 minutes so that the viewers could refresh themselves — it has become normative that the narrative also is divided into two more or less equal halves. This has given rise to the practice of ‘double climax’ structuring of the narrative.6 The narrative climaxes with an unexpected ‘turning point’ just preceding the interval, and this apparent ‘narrative discrepancy’ is sorted out in the post-interval half.

The following narrative schema highlights the general double climax structure centred on interval:

Phase 01 (The Beginning): It consists of establishing the narrative context, introducing the main characters, and initiating the central conflict.

Phase 02 (The Pre-Interval Development): The conflict initiated in the first phase undergoes a series of mutations with many twists and turns, acquires newer dimensions and gets more complex and intensified as the story moves ahead. Tension builds up, and as the interval approaches, it reaches its peak with a turning point.

Phase 03 (The First Climax): This ‘climax’ is a riveting turning point. It may involve an unexpected setback to the hero or villain, or a new mission entrusted to the hero, or the surfacing of a totally new problem. This keeps the viewers guessing during the interval as to what is in store for them during the next phase.

INTERVAL

Phase 04 (The Post-Interval Development): This phase starts with a twist, suspense or surprise, and with further turns and twists, the story moves forward towards the final showdown. The viewers are provided, through timely doses of back-story information, with additional and newer insights into the characters. Tension mounts as the climax approaches, the viewers’ involvement and expectations soar high, and the conflict swells up in magnitude and intensity.

Phase 05 (The Final Climax): It marks the direct confrontation of the hero and the villain. The climactic fight is the fiercest and the longest. The villain is defeated, the hero emerges victorious, the victims of villainy are rescued, and the core conflict is resolved with reversal of fortunes.

Phase 06 (The Denouement): The viewers are greatly relieved of their tension as the hero triumphs. In the denouement that follows, loose strings are tied up and the story is rounded off with a few finishing touches.

The intervention of interval then further ‘Indianises’ the narrative structure by radically transforming it to two ‘narratives’ disjointed and conjointed by the interval. In this sense, interval is a narrative, in as much as a commercial or convenience, device. In the films of MGR and RK special attention is being paid to the point at which the narrative is to be divided, because a bad break may fail to pull the viewers back into the movie house after the interval. Moreover, the double climax structure makes the ‘point of attack’ (the point at which the narrative opens) a lot more challenging, compared to the conventional single climax structure. In fact, the risk involved in deciding the three major points — the point of attack, the interval break point, and the final climax — is so great that even seasoned filmmakers find it unnerving to guess which combination would click with the audience.

Hero-Centricity

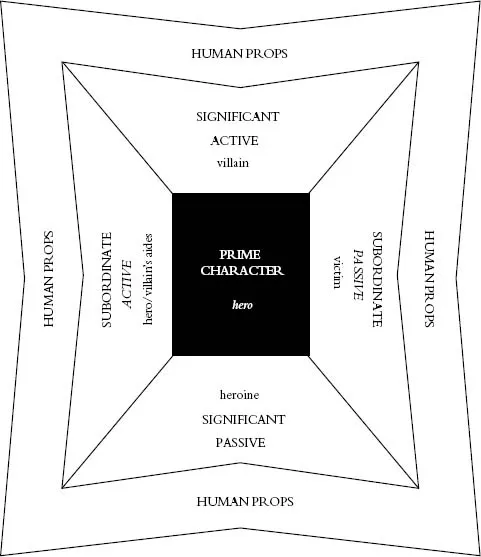

A functional analysis of the dramatis personae in a typical masala film reveals that there is only one prime character (the protagonist or hero), one significant active character (the antagonist or villain), one significant passive character (the heroine), one subordinate passive character (the victim), two sets of subordinate active characters (hero’s allies and villain’s aides), and other characters used as mere human props. This could be represented diagrammatically as shown in Figure 1.1.

Obviously, all the films of the popular stars are as a rule hero-centric. Characters other than the hero — significant or subordinate, active or passive — are clipped7 to heighten hero-centricity. These characters are linked up with the hero in a strict hierarchy, actualised through one or more of the following narrative cum technical devices:

• social8 positioning of the characters in terms of their relationship with the hero as per the narrative

• spatial positioning of these characters vis-à-vis the hero in the overall mise-en-scène

• visual perceptual positioning in terms of composition of shots and camera angles regarding the characters vis-à-vis the hero

• auro-lingual positioning of sound and language aspects concerning the characters vis-à-vis the hero

• temporal positioning in terms of duration of their screen presence vis-à-vis the hero

Figure 1.1

Hero-Centric Model of Dramatis Personae

Hero-Centric Model of Dramatis Personae

Source: All figures provided by the author.

The aforesaid and other such devices utilised are mixed with other masala elements within the selectively replicated socio-cultural universe. As the combined effect of this, the hero’s image emerges profoundly and prominently.

Snowball Dynamics

The image formation concerning commercially successful, politically motivated stars like MGR and RK is an evolutionary process, involving snowball dynamics. The core image created in one film is carried over to the next, reinforcing the previously constructed image and adding an embellishing and enhancing layer to it. The choice of the themes, the treatment and the characterisation are most often stereotypical, redundant and serial-episodic. By contrast, the films of Sivaji and Kamal, the forem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction: Popular as Political

- Part I: Politics of Narrative

- Part II: Politics of Body

- Part III: Politics of Imaging Politics

- Filmography

- Select Bibliography

- About the Author

- Index