![]()

I | THE THEORETICAL ROOTS OF PREVENTION |

![]() SOCIAL COGNITIVE VIEWS ON THE PERCEPTION OF HIV RISKS AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RISKY BEHAVIORS

SOCIAL COGNITIVE VIEWS ON THE PERCEPTION OF HIV RISKS AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RISKY BEHAVIORS![]()

1 | AIDS Risk Perceptions and Decision Biases |

Patricia W. Linville

Gregory W. Fischer

Duke University

Baruch Fischhoff

Carnegie Mellon University

Until effective vaccines against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are available for general public use, the major public health strategy for limiting the spread of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) will be through education about the risks of AIDS and instruction in strategies for reducing that risk. But developing effective educational programs requires a deeper understanding of how people think about the risks of AIDS and how they make decisions regarding those risks. Studies of risk perception and risk-taking behavior in other domains have identified a number of systematic biases in people’s risk perceptions and decision-making processes. These behavioral biases may lead people to make poor decisions that affect their risk of acquiring or spreading HIV infection. They also pose a significant obstacle to attempts to develop effective risk communications regarding AIDS and transmission of HIV.

In this chapter, we use models, methods, and findings from the field of behavioral decision research to analyze risk perceptions and decisions that affect the risk of HIV transmission. Behavioral decision research is an interdisciplinary subfield that integrates conceptions of rational decision making—from economics and statistics—with cognitive views of behavior developed in psychology. We consider three potential contributions of decision theory to the study of AIDS-related cognitions and behavior.

First, normative decision theory provides a set of concepts for thinking about and analyzing decisions that affect the risk of acquiring or spreading HIV. Normative decision theory addresses the question of how people should make inferences and decisions if they wish to conform to fundamental principles of logic and rational choice (Clemen, 1991; Keeney & Raiffa, 1976; von Winterfeldt & Edwards, 1986). Thus, the normative theory serves as a benchmark for evaluating the quality of the inferences and decisions that people make. In the first section of this chapter, we illustrate how the normative decision framework can be applied to several decisions affecting the risk of HIV transmission.

Second, behavioral decision research has revealed a variety of systematic biases in risk perceptions (e.g., Fischhoff & MacGregor, 1982; Slovic, 1987) and decision-making processes (e.g., Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982; Kahneman & Tversky, 1984). These biases complicate the task of formulating effective HIV risk communications. In this chapter, we present empirical findings regarding college students’ perceptions of the probability that they and others will acquire HIV infection. In analyzing these findings, we examine three types of cognitive bias that may adversely affect the decisions people make and that may also undermine efforts to communicate HIV risk information to the public: (a) an accumulation bias involving the inability to understand the relationship between the risk of acquiring HIV infection in a single sexual encounter and the risk of acquiring HIV infection in multiple sexual encounters; (b) a framing bias in which two logically equivalent descriptions of the effectiveness of condoms in preventing the transmission of HIV lead to systematic differences in people’s willingness to use condoms; and (c) an optimism bias regarding one’s personal risk of acquiring HIV infection. For each of these biases, we discuss implications for the composition of public health communications regarding HIV risk and protective strategies.

Third, behavioral decision research provides a set of tools for measuring perceived risk (e.g., Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein, 1982). In this chapter, we argue that these measurement procedures are especially likely to be helpful in the case of diseases like AIDS, where many individuals perceive their personal risk to be very small. We also describe a quantitative risk-assessment instrument that we have developed and used in a number of studies of HIV risk perceptions. Valid measures of risk perception are essential for assessing the public’s level of knowledge regarding risks of HIV infection. They are also needed to evaluate hypotheses about why people do or do not engage in various risky behaviors or self-protective strategies.

To preview what is to come, the first section of this chapter introduces the basic concepts of decision theory and shows how they can be applied to issues involving risks of HIV infection. The second section presents empirical data on three types of decision biases in thinking about HIV risks. The third section discusses issues surrounding the assessment of perceived risks of HIV infection.

THINKING ABOUT AIDS DECISIONS

A decision is a choice among competing courses of action. Most of the ways in which people contract and transmit HIV can be viewed as resulting from decisions. For instance, decisions about whether to have sexual intercourse and whether to use condoms largely determine who will be sexually infected with the virus. Decisions about whether to be tested for HIV antibodies influence the likelihood that infected individuals will infect others. Decisions about whether to share needles determine who will be infected by intravenous (IV) drug use. Even decisions about whether to pursue medical careers or to seek medical treatment may influence some individual’s risk of HIV infection.

Public policy decisions also affect HIV transmission. Decisions about whether to provide clean needles to addicts affect the number of victims of the disease. Decisions regarding levels of funding for drug treatment and education programs may influence the rate at which the virus spreads. Decisions regarding funding levels and priorities for AIDS research, treatment, and public information programs will partially determine how many more people will become infected and what their medical prognosis will be. Finally, decisions regarding who to accept as blood donors and what criteria to use in screening public blood supplies largely determine how many people will be infected by HIV-contaminated blood.

We begin this section by discussing how concepts and tools from decision theory can be used to represent and analyze decisions such as these. Next, we address the question: How should one make decisions that influence the risk of contracting HIV? We conclude the section by addressing the question: How are intuitive decisions likely to go wrong?1

The Decision Theory Representation of Decisions That Affect HIV Risk

Theories of decision making use five central constructs to describe and analyze decisions: courses of action, uncertain events, subjective probability, consequences, and utility. A graphical representation known as a decision tree is used to depict the relations among these constructs. The most widely used decision theory model, expected utility theory, provides a simple rule for combining these constructs to form an overall appraisal of the best course of action. In this section, we illustrate these concepts by showing how they can be used to describe a woman’s decision about whether to have sexual intercourse with a new romantic partner (who wishes to have sex with her) and, if so, whether to use a condom.

There are two possible uses of decision models like those we describe here. The first is scientific, or descriptive. Constructs in the model may represent important aspects of the decision-making process. The second use is normative, to assist in making better decisions. There are a number of decision theorists who act as agents for a variety of public and private decision makers. For instance, there is a small but thriving movement known as medical decision analysis in which physicians use decision theory methods to make difficult decisions regarding patient management (von Winterfeldt & Edwards, 1986).

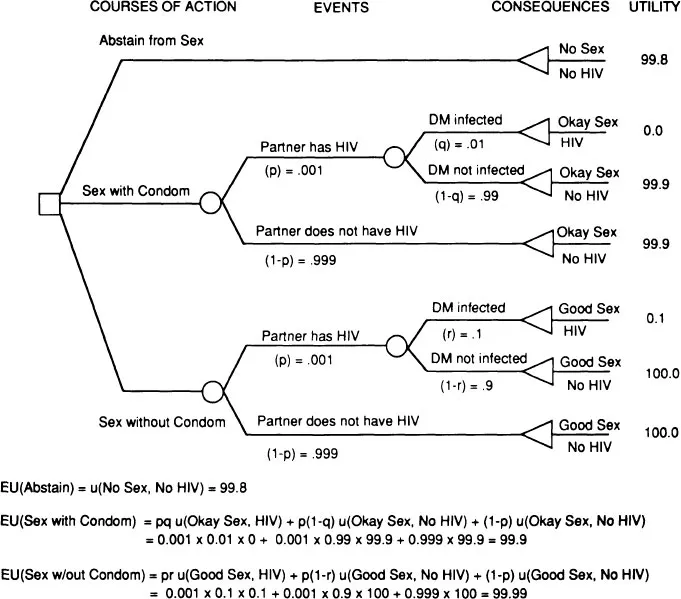

Courses of Action. A decision occurs when a person chooses among two or more mutually exclusive courses of action. For example, in deciding whether to have intercourse with her new romantic partner, the woman might consider three courses of action: (a) to refrain from having intercourse for the time being, (b) to engage in intercourse using a condom, and (c) to engage in unprotected intercourse. These courses of action are represented graphically as the first stage in the decision tree depicted in Fig. 1.1.

FIG. 1.1. Deciding whether to have sex and use a condom.

Uncertain Events. In many decisions, the path from acts to consequences is uncertain. Physical and social events intervene between an action and its consequences. For instance, is the woman’s new romantic partner HIV infected? If he is, will she contract the virus from him if she has sex with him one time with (without) using a condom? Uncertainty about the occurrence of such intervening events leads to uncertainty about the final consequences of a decision.

Subjective Probability. Decisions depend on beliefs about the likelihood of uncertain events like those just mentioned. If a decision maker’s beliefs about the likelihoods of events conform to a few basic principles of logic, then these beliefs can be represented by numbers referred to as subjective probabilities that quantify the degree of perceived likelihood of an event (Savage, 1954).2 The belief that an event is impossible is represented by a subjective probability of 0; the belief that an event is absolutely certain to occur by a subjective probability of 1; the belief that an event is as likely to occur as not by a subjective probability of 0.5; and so forth.

The decision represented in Fig. 1.1 involves three subjective probabilities. The first is p, the subjective probability that the decision maker’s partner is HIV infected. For instance, our decision maker might believe that there is only a 1 in 1,000 chance (p = 0.001) that her prospective partner is HIV infected. The second is q, the subjective probability that the decision maker will contract HIV if she has intercourse once, with an infected partner who uses a condom. She might believe this risk to be 1 in 100 (q = 0.01). The third is r, the subjective probability that the decision maker will contract HIV if she has intercourse once with an infected partner who does not use a condom. She might believe this risk to be 1 in 10 (r = 0.1). The values of q and r used in this example imply that the decision maker believes that the risk of acquiring HIV is only one-tenth as great with a condom as without.

Consequences. The consequences of a decision can be characterized by a set of value attributes reflecting the degree to which the decision results in the fulfillment (or frustration) of the decision maker’s goals or objectives. In deciding whether to have intercourse with a new romantic partner, the salient value attributes describing each potential consequence might include degree of sexual pleasure, quality of the romantic relationship, embarrassment at asking one’s partner to use a condom (if he does not offer to do so), becoming pregnant, and acquiring HIV. To simplify the example depicted in Fig. 1.1, only two value attributes are represented: the quality of the sexual experience (ranging from none to good) and whether the decision maker contracts HIV (yes or no).

When consequences depend on uncertain events that intervene between actions and the consequences themselves, the consequences are uncertain as well. The perception of such uncertainty contributes to subjective feelings of risk. For instance, the decision maker is uncertain as to whether having sex will lead to the consequence of contracting HIV. To simplify the example in Fig. 1.1, we have ignored uncertainty regarding the value attribute “quality of sexual experience.” Clearly, sex without a condom is not always “good” and sex with a condom is not always “okay.” We use these labels merely to summarize the decision maker’s expectation that sex will be more pleasurable (on the average) without a condom.

Utility. In decision theory, utility refers to a quantitative measure of the subjective desirability of a possible decision consequence. In standard practice, utility is scaled so that the worst possible outcome receives a utility of 0 and the best possible outcome a utility of 100.3 These utility scores reflect personal subjective preferences. Thus, different individuals may assign different utilities to the same outcomes.

For example, assume that the woman in our example believes that the best possible consequence is one in which she has sexual intercourse without a condom, which is highly pleasurable for both her and her lover (denoted by “good sex” in Fig. 1.1), and which does not result in the transmission of HIV. To anchor the top end of the utility scale, she assigns a utility score of 100 to this consequence (see Fig. 1.1). Further, suppose that the woman believes that the worst consequence is one in which she and her partner have moderately satisfying sex (“okay sex”) with a condom, but she contracts HIV infection. To anchor the bottom end of the utility scale, she assigns a utility of 0 to this consequence.

The other three decision outcomes in Fig. 1.1 receive utility scores between 0 and 100. Assume, for example, that our decision maker assigns a utility of 99.9 to the consequence “okay sex, no HIV,” indicating that she sees very little difference between this outcome and the best outcome, “good sex, no HIV.” She assigns a utility of 99.8 to “no sex, no HIV,” indicating that it is only slightly worse. Finally, she assigns a utility of only 0.1 to “good sex, HIV,” indicating that the decision maker views this outcome as being only slightly better than the worst outcome, “ok sex, HIV.” Collectively, these utilities indicate that avoiding HIV infection in the future is much more important to the decision maker than having a pleasant sexual experience in the present with her new romantic partner.

On what basis can utility scores like these be assigned to potential decision outcomes? Decision theorists have developed a variety of methods for measuring decision makers’ utilities for uncertain decision consequences. Some of these can be used by decision consultants (working as agents of the decision maker) or even by decision makers themselves if they wish to analyze their own decisions using the methods of decision analysis. In general, utility measurement procedures for risky decisions involve making comparisons between simple lotteries involving the consequences in question. A detailed discussion of these utility measurement procedures is beyond the scope of this chapter. (See Keeney & Raiffa, 1976, or von Winterfeldt & Edwards, 1986, for excellent descriptions.)

Expected Utility Theory. How should people make decisions involving uncertain consequences? This question has been investigated by economists, philosophers, psychologists, and statisticians for more than 200 years (e.g., Bernoulli, 1738). Theories regarding how people should make decisions are commonly referred to as normative—as contrasted with behavioral theories that ...