![]()

Chapter One

PREJUDICE AND RELATED TERMS; SCIENCE AND PREJUDICE

Prejudice has assumed great importance in social psychology, because of its connection with racial discrimination. In particular, many social psychologists have felt concerned about the anti-Semitism, anti-black, and anti-oriental discrimination, which has been a feature of societies in which ‘White Anglo-Saxon protestants’ form a majority, and has been a great disadvantage to members of these minority groups. The most influential study of the subject, and indeed a study that has had as much influence as any in social psychology, was the study which culminated in The Authoritarian Personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford, 1950/1964), which was begun during the second World War at the instance of the American Jewish Committee, who were concerned, for obvious reasons, with anti-Semitism.

This concern with social discrimination led to a bias in the study of ‘prejudice’, so strong that ‘prejudice’ was often defined in such a way as completely to ignore the original meaning of the term. Harding, Kutner, Proshansky, and Chein (1954) say: ‘By “prejudice” we mean an ethnic attitude in which the reaction tendencies are predominantly negative. In other words, a prejudice is simply an unfavourable ethnic attitude’ (p. 1022). Kutner (1952, p. 2) defines it as ‘…a readiness to respond to an individual or a group in terms of a faulty and inflexible generalization, the net effect of which is to place that person or group at a disadvantage.’ And Allport defines it as ‘an avertive or hostile attitude towards a person who belongs to a group, simply because he belongs to that group, and is therefore presumed to have the qualities ascribed to the group.’ (1958, p. 8)

All these definitions, which are typical of definitions in the literature, agree in confining the term to ‘negative’ or ‘avertive’ or ‘hostile’ judgements, and the first does not directly refer to beliefs or opinions. Allport does take some pains to justify his definition, taking into account the dictionary definition of the word. The Concise Oxford Dictionary (fourth edition) gives us ‘preconceived opinion’. The dictionary thus gives us a definition which embraces much more than is commonly done by psychologists. Neither does there seem to be any good reason for confining the definition to an ‘unfavourable ethnic attitude’. This kind of definition gained currency simply for historical reasons, not for any rational reason. Its use obscures the important consideration that our prejudices are not confined to ethnic groups, and that they do not necessarily or invariably entail unfavourable judgements or opinions. One can be prejudiced in favour of black Englishmen, as well as against them; and one’s prejudices can concern motor-cars and tinned soup as well as ethnic groups. I suspect that I, and many other social psychologists, are prejudiced against people we classify as ‘racists’. Hence, I take the definition of prejudice to be: ‘an opinion or belief held by anyone on any subject which, in the absence of or in contradiction to, adequate test or logically derived conclusions or comparison with objective reality, is maintained as fact by the person espousing it, and may be acted on as though it were demonstrably true’. This definition is not very different from Hazlitt’s written in the early nineteenth century: ‘Prejudice, in its ordinary and literal sense, is prejudging any question without having sufficiently examined it, and adhering to our opinion upon it through ignorance, malice, or perversity, in spite of every evidence to the contrary’ (1852/1970, p. 83). His classic little essay on the subject is well worth reading: the work of psychologists on the subject would be less confused if his essay were widely read.

The fundamental problem of prejudice, from the point of view of the cognitive psychologist, is to explain how it comes about that people make judgements and apparently believe things, or act as though they believe them, in the absence of adequate evidence. From the point of view of the person interested primarily in groups, the focus of interest is how prejudice affects the relations between members of different groups, and the part played by a person’s identifying with a particular group in the formation of prejudices. These ‘group’ questions are dealt with in chapter 6.

Some observations about prejudice and its definition are called for. That prejudices may be favourable or unfavourable, and they may concern any kind of object has been said. But it is wise further to note that we are all prejudiced, since not even by the most liberal definition of the terms, can any of us be said to have subjected many of our opinions to ‘adequate test’ etc. Life is too short for us to find out or check everything for ourselves. The question then arises, when is prejudice important? The answer is a value judgement. The implied answer of many social psychologists is that one area in which it becomes important is when innocent people are made to suffer, as is the case when people hold prejudices about members of other ethnic groups. The impetus for research on prejudice in social psychology has come from the emotional commitment of many social psychologists to non-racialism, or to redressing what they see as the wrongs non-white people have suffered at the hands of Whites.

Further, let it be observed that the definitions which include the term ‘attitude’ are not so different from the definition suggested as may at first appear. Recall that ‘attitudes’ are defined in terms of ‘feelings’ and that attitudes usually have beliefs and action tendencies associated with them. The co-relation between feelings, beliefs, intended behaviour, covert behaviour, and overt behaviour, is made clear below.

SOME TERMS RELATED TO ‘PREJUDICE’

Let us look at some allied terms, which are often used interchangeably with prejudice.

Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism means a tendency to glorify the ingroup while denigrating outgroups; usually there is an implicit suggestion of the ingroup being at the centre of a series of concentric circles, each circle representing an outgroup, attitudes towards which become increasingly more unfavourable as the number of circles between it and the inner-most circle (ingroup) increase in number. In fact, as will be seen, ethnocentrism is usually measured by an ‘E scale’, and a look at this scale shows it to be a fairly direct measure of ethnic prejudice. Operationally, that is, the terms ‘ethnocentrism’ and ‘ethnic prejudice’ are the same.

Intolerance

Intolerance refers to a tendency to disapprove of things one dislikes: it is conceptually quite distinct from ‘prejudice’ though empirically it may be that intolerant people are very often also prejudiced.

Dogmatism

Dogmatism refers to the tendency to assert untested opinions in an arrogant or authoritative way. (There has been only one major, published attempt to measure dogmatism, by Rokeach, 1960. His dogmatism scale, designed to measure the extent to which people’s belief systems are ‘open’ or ‘closed’, is of dubious validity.) The similarity of dogmatism to prejudice is clear, the special feature of dogmatism being the expression of a prejudice in an authoritative or arrogant way.

Rigidity

Rigidity means the relative inability to shift from one line of thought or hypothesis to another, when dealing with any problem or task. No really satisfactory measure of this quality has been produced, so it is to some extent doubtful whether it is the case that some people are more rigid than others – that is whether a trait of rigidity exists. In fact, a large number of putative measures exist, but all are open to criticism, as to their reliability or validity. One such test is the ‘water-jar test’ of rigidity. This test consists of a number of simple arithmetic problems which can all be solved in the same way, followed by one which can be solved either in that way or in another, simpler way: the response supposed to indicate rigidity is a solution of the task in the same way. Leavitt (1956) in a review of this test concludes:

1. After eight years of research, evidence for the validity of the water-jar test is still lacking.

2. The water-jar test is a poor test qua test (p. 369).

A variety of pencil-and-paper tests are available, but the evidence for their validity is lacking. The problem is partly that the term has often been defined loosely. There is strong evidence that emotional stress increases rigidity in the sense that the term is used here (Ainsworth, 1958; Luchins & Luchins, 1969; Ray, 1965). That partly explains why people seem to stick most closely to their prejudices at times of stress and conflict.

Stereotype

Stereotype is defined in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary as something ‘continued or constantly repeated without change.’ In psychology this ‘something’ is a response of some sort, and we are most interested in cognitive ‘responses’. It means to respond (by categorizing, or by behaving in the same way towards) to a group of discriminable stimuli as though they were identical. In other words, stereotype is the assumption of considerable similarity between members of groups or categories where such groups are defined in terms logically and empirically unrelated to the characteristics assumed to be common to members. The term is a metaphor from the printing trade: originally it meant a metal plate, which always produced the same image on paper. Its present use was originated by the American journalist, Walter Lippmann, early this century (Lippmann, 1922/1956). Classic measures of stereotypes (Katz & Braly, 1933/1961) consisted of a list of adjectives, with instructions to respondents to mark those that applied to certain groups – Jews, black Americans, etc.. This technique has been criticized (Brigham, 1971) on the grounds that Mann (1967), among others has shown that people are not as inconsistent as this kind of test makes them appear: not even the most prejudiced white person thinks all black people are lazy, dirty, etc. It is probably better to ask respondents to say what proportion of the group have the characteristics in question, if one is interested in individual responses. If one is interested in groups’ responses, however, and does not draw strong inferences about individuals from it, the Katz and Braly approach is perfectly adequate. Bethlehem (1969) used a series of bipolar rating scales (e.g. altruistic – selfish; cold-hearted – warm-hearted as a measure of stereotype. A number of measures have been used as indices of intra-group agreement about what traits characterize the outgroup. Katz and Braly (1933/1958) for instance used the smallest number of adjectives that would have to be included to account for 50% of their subjects responses. More sophisticated indices have been suggested by Freund (1950) and by Lambert and Klineberg (1959). They all produce indices that are high when subjects agree with one another about what adjectives characterize the outgroup.

More recently it has been suggested that one should concentrate, in measures of stereotypes, not on the characteristics ascribed to a particular group, but on the characteristics ascribed with a particularly high probability to members of that group and with lesser probabilities to members of other groups. A good way of measuring this difference is in terms of the likelihood- or diagnostic ratio.

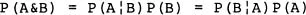

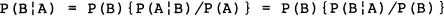

In terms of conditional probabilities, the multiplication rule tells us that

(NOTE: ‘A&B’ – say ‘A and B’; ‘A|B’ – say ‘A given B’.)

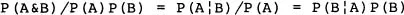

Dividing through by P(A)P(B), we see that

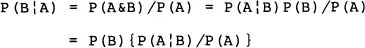

The conditional probability of an event, B, given that event A has occurred, is

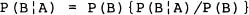

That is, to find the probability of event B, given that A has occurred, we multiply the probability of event B by the probability of event A given B over the probability of A. Or we can multiply the probability of event B given A over the probability of B, since we have shown that

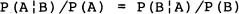

Hence

The terms P(A|B)/P(A) and P(B|A)/P(B) are known as likelihood or diagnostic ratios. These ratios tell us the factor by which we must multiply the simple probability of an event when we know that that event is conditional on another event.

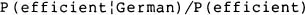

To illustrate the application of the above: McCauley and Stitt (1978) asked students to estimate a number of probabilities and conditional probabilities, to do with the known stereotypes of Germans. They estimated, among other things, the percentage of the world’s population who are efficient [P(efficient)] and the percentage of Germans who are efficient [P(efficient|German)]: this latter is akin to the usual meaning of stereotype. They were then able to calculate the diagnostic ratio

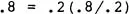

i.e., the probability that a person is efficient given that he is German divided by the probability that anyone in the world is efficient. If a person judges that Germans are more likely to be efficient than just anyone, this diagnostic ratio will be greater than 1. That is, it tells us that knowing a person is a German increases the (subjective) probability that he is efficient relative to just anyone. To give another example, let A stand for ‘university lecturer’ and B for ‘lazy’, and let us suppose that the probability that a university lecturer is lazy P(B|A) is .8, and the probability that a random person whose occupation we don’t know is lazy is .2. Then

Hence

The diagnostic ratio (.8/.2) is 4. That is, given that we know that a person is a university lecturer, we are much more sure that he is lazy than we would be if we did not have that information. McCauley and Stitt (1978) show that it is indeed the case that for characteristics which form part of Americans’ stereotype of Germans, as indicated by a previous study, (efficient, extremely nationalistic, industrious, and scientific minded), diagnostic ratios calculated in this way are greater than 1, and for other, non-stereotype characteristics (e.g. superstitious) the diagnostic ratios are less than 1. They suggest that this diagnostic ratio

should be used as a measure of stereotype.

This idea, though probably close to the intuitive ideas of many people, is a departure from the definition of stereotype quoted above. It would mean that if a person had the view that a very high proportion of Jews are dishonest, and that a very high proportion of members of other outgroups are also dishonest, then ...