![]() Part I

Part I

Central American tropical forests, ecosystem services and human wellbeing![]()

1 An overview of forest biomes and ecoregions of Central America

Lenin Corrales, Claudia Bouroncle and Juan Carlos Zamora

Introduction

Central America is situated between the Nearctic and the Neotropical biogeographic realms, which have produced conditions for relatively high levels of biological diversity, with important ecoregions, ecosystems, endemism, and species richness. The Central America region comprises El Salvador, Belize, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, and it has been identified as part of one of the planet’s richest and most highly threatened biodiversity regions, making it one of the world’s top 25 biodiversity conservation hot spots. Considering species diversity and endemism, Central America is the world’s second ranking priority hot spot in terms of plant and animal endemism, and fifth among all hot spots (Myers et al. 2000; Conservation International 2011).

This chapter describes the terrestrial ecoregions of Central America and its nested biomes based on the analysis framework proposed by Dinerstein et al. (1995) for setting priorities of conservation. Ecoregions provide a conceptual framework for the identification of representative habitats and serves as a tool to compare areas with different biodiversity features, status of their natural habitats and degree of protection (Olson et al. 2001). The description of their biotic characteristics, landscape context, main threats to loss of biodiversity and degradation caused by human activities and conservation status is based on the available literature but also on spatial analysis at regional scale.

Biomes and ecoregions description

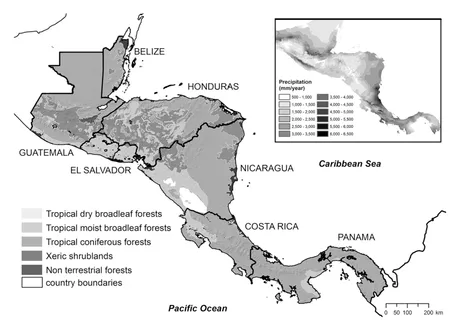

The Selva Maya in Guatemala and Belize and the Darien forest in Panama are the northern and southern ends of Central American ecoregions. The isthmus (80–500 km wide) is bordered by the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea and divided by a mountain range reaching higher elevations in Guatemala and Costa Rica (4220 m on Mt. Tajumulco and 3820 m on Chirripó, respectively; DeClerck et al. 2010). The distribution and biophysical characteristics of four terrestrial tropical biomes (major terrestrial habitats; Olson et al. 2001; Figure 1.1) and 19

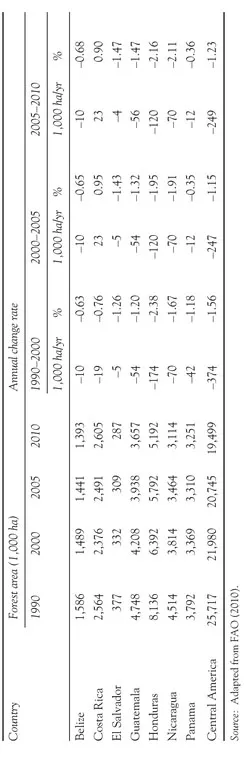

Box 1.1 Forest types and land use change in Central America

The forest cover in Central America has been changing since pre-Columbian times (Piperno 2006). After the Spanish conquest, the conversion of the Pacific dry broadleaf forests started with the introduction of cattle production in 1521 (Heckandon 2003). Studies for Costa Rica illustrate the role played by the agroecological conditions in the spatial patterns of deforestation and fragmentation common in the region, clearly showing two processes: the progression of vegetation loss from dry and low areas and towards wetter and steeper areas and the fragmentation of forest remnants associated with the expansion of annual crops and pastures (Finegan and Bouroncle 2008). The expansion of the cattle production and agriculture reached the wet Atlantic lowlands in the last decades of the XIX century, such that virtually no place of the Central American isthmus remains unaffected (Table 1.1). Other drivers of human -induced biodiversity loss that are increasing its significance, are over-exploitation of natural resources, water pollution (Programa Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible 2001), introduction of non-native species (Harvey et al. 2005a) and climate change (e.g. CATHALAC 2008; Clark et al. 2003; Feeley et al. 2007; Pounds et al. 2006; Whitfield et al. 2007).

Today the most important agricultural commodities in the region are coffee, sugarcane, oil palm, bananas and other tropical fruits, which accounted for 14 per cent of the total goods exported from the Central American countries in 2012 (ECLAC 2014). However, in terms of total land area occupied, the dominant agricultural land use is pasture for cattle raising which accounts for 2 to 46 per cent of the land use depending on the country, the importance of other agricultural activities varies across countries (FAO 2014). Basic grains (i.e. rice, corn, beans, sorghum) are the second-most common agricultural land use in El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras, whereas in Costa Rica, Belize and Panama, no single agricultural crop dominates (Harvey et al. 2005a). Although the economic importance of agriculture has declined in recent decades in all Central American countries except Nicaragua, it still remains an important economic activity, contributing to an estimated 7 to 36 per cent of the total gross domestic product per country (Programa Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible 2011).

Although highly deforested and fragmented, many of the landscapes still retain some on-farm tree cover, in the form of small (and often isolated) forest fragments, strips of riparian forest, dispersed trees in pastures, fallows and/or live fences. This on-farm tree cover is important for both farm productivity (providing shade and forage for cattle, while providing timber and firewood to farmers), and for biodiversity conservation at different scales (e.g. providing important habitat and resources to wildlife, as well as serving as corridors or stepping stones that facilitate animal movement) (Harvey et al. 2005b, 2008).

Table 1.1 Forest area changes in Central America between 1990 and 2010

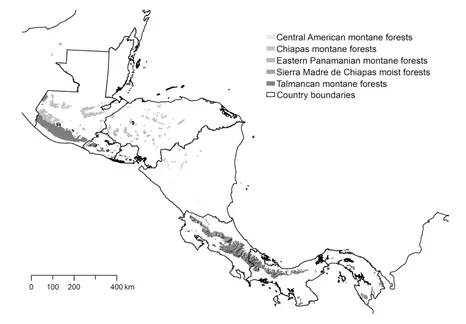

terrestrial ecoregions (distinct assemblage of natural communities and species; Olson et al. 2001; Figures 1.2–1.5) are related to the physiography and precipitation distribution in the region, according to the Holdridge life zones (1979) that were used to delineate biomes and ecoregions in Central America (Dinerstein et al. 1995). Considering their community types and potential distribution, the most extensive are the moist broadleaf forests (55 per cent of the terrestrial area of the region), the coniferous forests (24 per cent), and the dry broadleaf forests (20 per cent), one per cent is covered by xeric shrublands. The montane ecoregions of the moist broadleaf forest and the coniferous forests biomes contains tropical montane cloud forests, ecosystems with characteristic structure and flora that occur in an altitudinal range with a seasonal or persistent cloud cover that receive higher precipitation and lower evapotranspiration (Brown and Kappelle 2001; Sáenz and Mulligan 2013), and in consequence are critical for the provision of hydric ecological services.

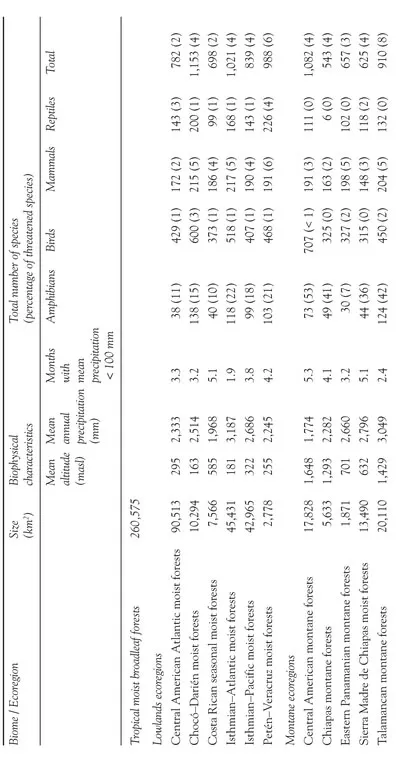

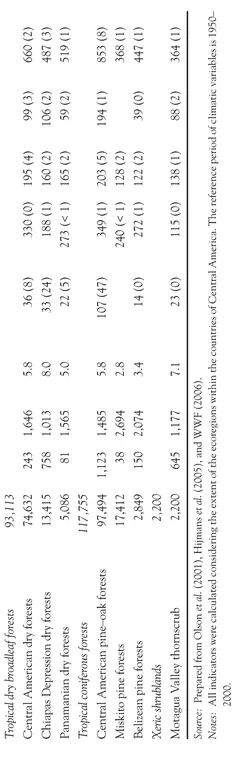

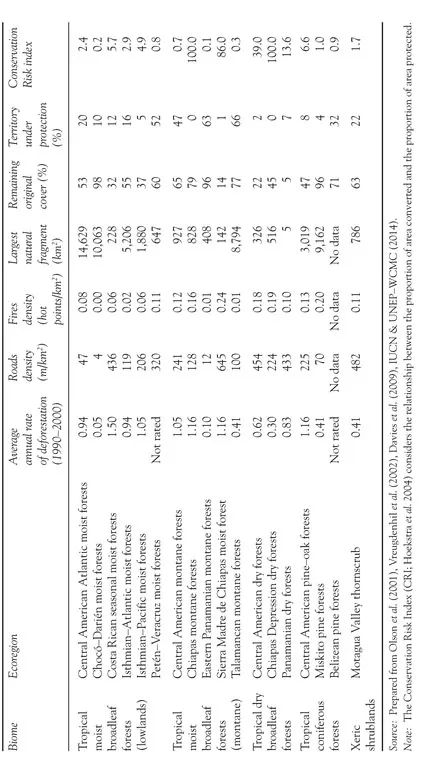

Each ecoregions average altitude, average annual rainfall, and dry months (Table 1.2), calculated from spatial databases, show the relationship between these biophysical characteristics of the ecoregions and species number of some vertebrate taxa. The values of indicators of ecoregions threats, ecologic integrity and conservation status of the Central American ecoregions (Table 1.3), also calculated from spatial databases, illustrate the different degrees of land use change on the ecoregions for the year 2000.

Figure 1.1 Biomes of Central America Source: based on Olson et al. (2001) and Jarvis et al. (2008).

Table 1.2 Biophisical characterization and species richness of ecoregions in Central America

Table 1.3 Indicators of ecoregions threats, ecologic integrity and conservation status in Central America (year 2000)

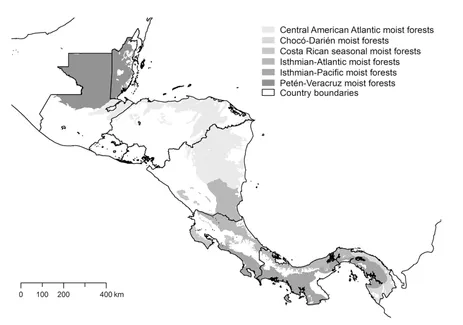

Tropical moist broadleaf forests

This biome is by far the largest, considering it potential distribution. It is also the one that contains the highest number of ecoregions. In Central America, it extends in a continuous strip from Guatemala to Southern Panama, along the Atlantic Coast in lowlands and montane areas (Figure 1.1) with low annual temperature variability and high rainfall (2000–3200 mm annual precipitation). The forests is dominated by semi-evergreen and evergreen deciduous tree species arranged in up to five strata, and is the highest in species diversity in any terrestrial biome in the world. According to their altitudinal distribution, the ecoregions of this biome in Central America can be grouped in lowlands and montane ecoregions. The first ones are distributed in continuous strips (Figure 1.2), while the montane ecoregions are naturally fragmented (Figure 1.3).

In general, the ecoregions of this biome are in very different states of ecological integrity, reflecting the intensity of human productive activities and land occupation. The humid forests of the Chocó Darien ecoregion have the best ecological integrity (98 per cent of remaining original cover) in Central America while the Costa Rican seasonal moist forests have the worst (32 per cent of remaining original cover) and the higher natural habitat loss rate.

Figure 1.2 Tropical moist broadleaf forests (lowland) ecoregions of Central America Source: based on Olson et al. (2001).

The Central American Atlantic moist forest ecoregion covers the lowland Atlantic slopes of northern Central America and is the second largest ecoregion in the isthmus (Figure 1.2). It is in the middle range of species richness in Central America (Table 1.2), with characteristic tropical evergreen forest with canopy trees reaching 50 m in height (Powell, Palminteri, and Schipper 2001a).

Figure 1.3 Tropical moist broadleaf forests (montane) ecoregions of Central America Source: based on Olson et al. (2001).

The main drivers of habitat conversion are the agricultural and infrastructure expansion, wood extraction and other indirect causes (Geist and Lambin 2001). About half of the original habitat remains and the ecoregion conserves natural habitat fragments bigger than 100 km2 (Table 1.3), a size than could maintain viable populations of large vertebrates (Dinerstein et al. 1995; Powell, Barborak, and Rodriguez 2000); the low density of habitat fragments is related to a low degree of fragmentation, fires and roads density are not critical for this ecoregion (Table 1.3).

The Chocó-Darién moist forests ecoregion covers lowlands in eastern Panama in Central America (Figure 1.2) and the entire Pacific Coast of Colombia. This is one of the few places in the Neotropics with pluvial rainforest (D’Ambrosio 2001). This ecoregion is the richest of Central America, considering the total species of amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles (Table 1.2); it is also considered one of the most biodiverse lowland areas in the world, with exceptional abundance and endemism of plants, birds, amphibians, and butterflies. The ecoregion has the best ecological condition in the region since almost the entire original habitat remains in large forest blocks with minimal fragmentation and high connectivity. The proportion of natural habitat converted is very low (Table 1.3) due to its low population density and Panamanian regulations on livestock expansion activities.

The Costa Rican seasonal moist forests ecoregion lies between the crests of Costa Rica’s Central Volcanic Cordillera and the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1.2). It is naturally fragmented and covers the Pacific slopes, most of the Nicoya peninsula and small areas in Nicaragua. These forests link mountain tops and the Atlantic slopes, an aspect that facilitates the migration of many species (Imbach et al. 2013). Deciduous trees that lose their leaves during the dry season dominate these forests (Powell, Palminteri, and Schipper 2001b). Only one third or the original habitat remains and is very fragmented (as can be deduced from the high density of fragments remaining habitat, the highest between the Central American ecoregions) with fragments smaller than 50 km2 (the minimal habitat size for middle-size felines; Stiles and Skutch 1989). However, these small fragments can be valuable to preserve communities and representative species, as well as stepping stones for ecological connectivity. This ecoregion has the higher loss rate of original habitat, two of the main causes of habitat loss have been the agricultural expansion and development of major cities in Costa Rica across what is called the Central Valley (see the high level of roads density in Table 1.3).

The Isthmian-Atlantic moist forest ecoregion covers lowlands from southern Nicaragua and along the eastern Caribbean Coast of Panama (Figure 1.2) with high rates of precipitation. The forests have a complex structure that includes palms in the medium canopy strata, and a very rich epiphyte flora. This ecoregion is the second richest of Central America, considering the total species of amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles (Table 1.2). Seasonal swamp forests occur in the lowest and flattest areas in Nicaragua and northern Costa Rica (Powell, Palminteri, and Schipper 2001c). The main driver of habitat conversion is the agricultural expansion, high road density is concentrated in Costa Rican and Panama areas (Table 1.3), so it is expected that the degree of fragmentation differs along the ecoregion.

The Isthmian-Pacific moist forest ecoregion includes the slopes from southern Costa Rica and eastern Panama (Figure 1.2). Its location in the Intertropical Convergence Zone makes it one of the wettest in the region, as the moisture-laden winds from both the north and south collide causing a long rainy season and a short dry season. Many species of South American affinity find here i...