eBook - ePub

Pronouns and Word Order in Old English

With Particular Reference to the Indefinite Pronoun Man

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pronouns and Word Order in Old English

With Particular Reference to the Indefinite Pronoun Man

About this book

First published in 2003, this is a study of the syntactic behaviour of personal pronoun subjects and the indefinite pronoun man, in Old English. It focuses on differences in word order as compared to full noun phrases. In generative work on Old English, noun phrases have usually divided into two categories: 'nominal' and 'pronominal'. The latter category has typically been restricted to personal pronouns, but despite striking similarities to the behaviour of nominals there has been good reason to believe that man should be grouped with personal pronouns. This book explores investigations carried out in conjunction with the aid of the Toronto Corpus, which confirmed this hypothesis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pronouns and Word Order in Old English by Linda van Bergen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 Aims and structure of the thesis

It has long been acknowledged that the behaviour of pronouns in Old English may deviate from that of full noun phrases in aspects of word order. This holds for generative work and non-generative work alike. Not everyone agrees on the precise nature or extent of this deviation, however. Some restrict separate treatment to pronouns in a particular syntactic function, while others restrict it to a specific subclass of pronouns. Thus, there are studies that make a distinction between a pronominal and a nominal category when objects are concerned, but do not extend the same treatment to subjects. And in generative work in particular, a strict division is normally made between personal pronouns on the one hand and all other categories on the other; somewhat confusingly, these two categories are normally referred to as ‘pronominal’ and ‘nominal’, so that most types of pronouns are classified as ‘nominal’. Yet other pronouns have sometimes been grouped together with personal pronouns, particularly in non-generative work. Fourquet (1938) for example explicitly treats the following pronouns as members of a class whose behaviour is distinct from nominals: personal pronouns, the demonstrative pronoun se ‘that’ and man ‘one’.1 And the assumption in most generative work that all pronouns other than personal pronouns can be grouped together with full noun phrases for the purposes of dealing with their behaviour relating to word order has not been tested in any systematic way.

In this thesis I aim to settle the issue for one specific pronoun: the indefinite pronoun man. The classification of this particular lexical item may seem a fairly minor issue, but it is of importance in data work on for example verb second. Moreover, it will be shown that the behaviour of man leads to problems of analysis which have a wider impact. This pronoun frequently occurs in syntactic patterns which appear to show that its behaviour matches that of nominals. Consequently, it has normally been assumed in generative work that man should be treated as nominal (in the use of the term mentioned above). Nevertheless, I will demonstrate that other aspects of its distribution firmly point to the opposite classification. In a number of earlier non-generative studies it had already been suggested that the behaviour of man is like that of other types of pronoun such as personal pronouns (Roth 1914 and Fourquet 1938, followed to some extent by Bacquet 1962). However, the data in these early studies are insufficient and do not make all relevant distinctions, so that no conclusions can be based on them. The issue does not seem to have been followed up in any subsequent work. Indeed, the potential problem has not been pointed out in later work classifying man as nominal. The only treatment I have seen of man as ‘pronominal’ in the generative literature, Haeberli and Haegeman (1995), does not base this assumption on any evidence and they appear to be unaware that such a classification conflicts with other generative work.

This dissertation offers a comprehensive study of the behaviour of man focusing on word order, especially those aspects in which the behaviour of personal pronoun subjects deviates from that of nominal subjects. I will show that the resemblance to the nominal pattern of behaviour is superficial only, and that man should not be grouped with nominals in any environment. It will be argued that the best way of dealing with the apparent contradiction is found in an analysis of ‘pronominals’ (including man) as clitics. In addition, there are indications that the classification of certain other types of pronoun as ‘nominal’ is unsafe. This holds specifically for the demonstrative pronoun se, and possibly also for the indefinite pronoun hwa ‘someone’. Moreover, some of the constructions found in the course of the data collection on man lead to further insights into the behaviour of pronominal subjects, verb placement and clause structure.

The structure of the thesis is as follows. In the remainder of this chapter I will deal with preliminary issues. I will discuss the ways pronouns have been treated in studies on word order in Old English so far, paying particular attention to non-generative work, in which pronominal subjects have only rarely been distinguished from nominal subjects in any systematic way. (Most of the discussion of the generative literature is postponed to the more theoretically oriented part of the dissertation.) This is followed by some background information on the corpora and other resources used in this study. Finally, there are two brief sections containing some remarks on the data and the theoretical framework respectively.

The next two chapters discuss the main data work. Chapter 2 is concerned with inversion — or lack of it — in main clauses with a topicalised constituent. A preliminary investigation on the behaviour of man in clauses with topicalisation was done using the Brooklyn-Geneva-Amsterdam-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English, Cura Pastoralis and the works of Ælfric, to determine whether man behaved as a nominal or a pronominal subject in relation to inversion.2 When it became clear that at least in this respect the behaviour of man was more regular than anticipated — indeed categorical once allowance was made for the special behaviour of negated and subjunctive verb forms — a full investigation of man was done with the aid of the Toronto Corpus to confirm these findings and to locate counter-examples. The same investigation of the Toronto Corpus also provided most of the data for chapter 3. In that chapter, I address the apparent contradiction between the findings of chapter 2 and the two constructions in which man seems to behave as a nominal. These two constructions involve subordinate clauses and clauses with inversion of all subject types. I show that even in these environments strong indications can be found that man essentially behaves in the same way as personal pronoun subjects. Also, I demonstrate that there are differences between the behaviour of man and nominal subjects in the two syntactic patterns that superficially appear to show that man behaves as a nominal subject. I conclude that man can certainly not be treated as nominal, and that there are good reasons for grouping it together with personal pronoun subjects.

Note that I have deliberately kept technical terminology and discussion of a theoretical nature to a minimum in the main discussion of the data. This was done with the aim of keeping at least these parts of the work accessible to those primarily interested in the philological aspects of the thesis. A complete separation of data and theory has proved impossible, however. Some theory has almost inevitably crept into the two chapters focusing on data, although I have tried to limit it to an occasional footnote, and some issues of data have spilt over into the following two chapters. The result may satisfy neither philologist nor theorist completely, but I hope there will be enough of value for either to compensate for any minor inconvenience.

Chapters 4 and 5, then, deal with issues of analysis. Chapter 4 focuses on what precise status should be assigned to man, and whether this is the same as that of personal pronoun subjects and/or objects. In it I argue that the best way of dealing with the data can be found in a clitic analysis of all of these, in spite of the fact that it has proved difficult to define the clitic host.3 It is demonstrated that, to the extent that Old English pronominals meet criteria for clitic status, the evidence is at least as good for man as for personal pronouns. I also show that the data on man indicate that a weak pronoun analysis (in the use of the term as found in recent generative analyses such as Cardinaletti and Starke 1996, 1999a) is not possible for Old English. This in turn undermines the argument for having this category at all, since it cannot deal with all cases of clitic-like pronominals for which a host is hard to establish. Chapter 5 focuses on the implications of the findings for analyses of Old English clause structure. I show that the data on negated and subjunctive verb forms uncovered in chapter 2 prove that the structural position of the topic must be spec-CP rather than spec-IP. In addition, I argue that topicalisation in subordinate clauses should be allowed for. Finally, it is shown that, given the analysis of Old English clause structure adopted, incidental cases of pronominal inversion in clauses with topicalisation fall into place as well.

1.2 Pronouns and studies on Old English word order

It is more or less taken for granted in most generative work on Old English that personal pronouns form a separate class whose behaviour deviates in significant ways from that of nominals, and that this holds irrespective of function. Van Kemenade (1987) has proved particularly influential in promoting this view.4 Yet such a view is by no means universal. Specifically, in a number of studies object pronouns are treated as a special case, whereas subject pronouns are not. This is particularly striking in relation to their placement relative to the (finite) verb in main clauses. Since my main concern is precisely with pronominal subjects, I will go into this a little further before turning to the main issues of the thesis.

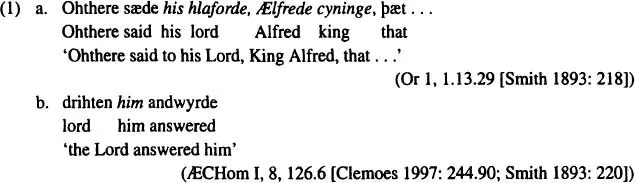

Smith (1893: 218–221) treats pronominal objects separately from non-pronominal objects, with nominal objects in main clauses normally following the (finite) verb as in (1a), but pronominal objects tending to precede it, as in the example given in (1b).

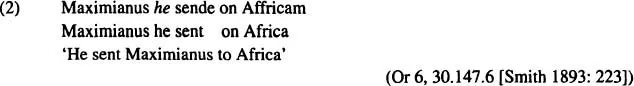

He ascribes this difference to general properties of pronouns, in particular their reference to nouns mentioned earlier in the text, so that they are according to him relative in nature, “and just as relative pronouns proper follow as closely as possible their antecedents, so personal pronouns, partaking of the relative nature, partake also of the relative sequence” (Smith 1893: 221). Yet in his treatment of inversion, he makes no comparable distinction for subjects. Indeed, having given three examples without inversion after a fronted object, all of which involve personal pronoun subjects, he ascribes the lack of inversion to “the superior distinctness with which these names [i.e. the fronted objects — LvB] are contrasted, not only by their being placed first but equally by their not drawing (though they are direct objects) the verb with them” (Smith 1893: 223). I give one of his examples in (2).

He goes on to suggest that the lack of inversion facilitates pausing after the fronted object, whereas such a pause according to him would not have been possible had the subject been inverted. He states that “In these cases, therefore, rhetoric has disturbed what must still be called the usual norm [emphasis mine — LvB]” (Smith 1893: 223), offering a hypothetical version with inversion (“Max. sende he”) to illustrate the difference in effect as he perceives it. In other words, he does not even consider the possibility that the nature of the subject could have had any influence on the order found, in spite of the fact that his explanation for the frequent placement of object pronouns preceding the finite verb could easily be extended to pronominal subjects.

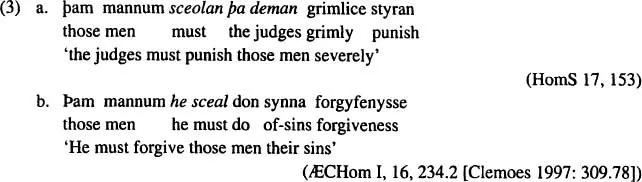

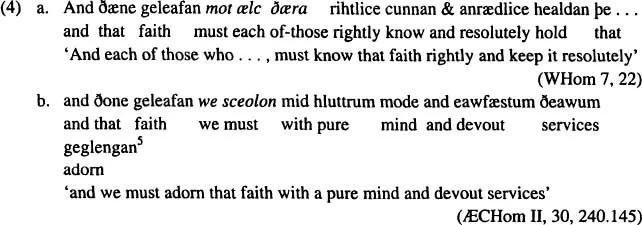

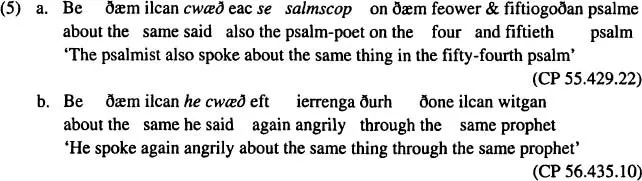

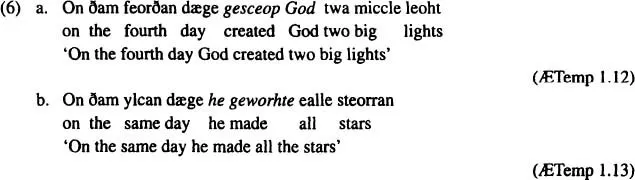

Inversion of a personal pronoun subject after a fronted object as in (2) — or after a prepositional phrase for that matter — would in fact have been highly unusual. See for example Allen (1980: 49), who observes that “While inversion is more common after Topicalization than non-inversion if the subject of the sentence was a full noun, I have found no examples of inversion of a pronominal subject with the verb after a topicalized object or prepositional phrase”. I give some sets of examples with inverted nominal subjects and non-inverted personal pronoun subjects in a comparable environment in (3)-(6) to illustrate the difference in behaviour.

The problem in Smith (1893) appears to stem from a lack of a consistent distinction between the different types of fronted constituents. Although Smith (1893: 222) is clearly aware that inversion is much more frequent after some initial constituents (such as þa ‘then’ and þonne ‘then’) than after others, it is easy to miss or underestimate the consistency with which personal pronoun subjects fail to invert in certain contexts unless the different types are consistently kept separate. This, at any rate, is clearly what happens in Bacquet (1962), who is fully aware of the claims made in this respect by both Roth (1914) and Fourquet (1938). Although he agrees with them that pronominal subjects generally speaking are less likely to invert, he does not think a categorical distinction is justified. Therefore he does not separate his examples according to type of subject, nor does he formulate any rules making specific reference to nominal and pronominal subjects respectively. “Si les phrases attestant l’ordre: verbe – sujet pronominal sont moins fréquentes que celles où l’on trouve l’ordre: verbe – sujet nominal, il n’en reste pas moins vrai qu’elles sont trop fréquentes pour que l’on puisse les considérer comme des faits accidentels” (1962: 659). On the other hand, he regularly distinguishes object pronouns from nominal objects in his rules describing the ‘unmarked’ word order in Alfredian Old English.

Reszkiewicz (1966) also...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Topicalisation and (non-)inversion

- 3 Other aspects of word order in relation to man

- 4 On the status of man and personal pronouns

- 5 Topics in Old English clause structure

- 6 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index