![]()

1 | MEANING AND GRAMMATICALITY PREDICTION IN GENERATIVE GRAMMAR |

Within current Transformational Generative Grammar a grammar is regarded as a set of rules relating sound to meaning. These rules must generate all and only the grammatical sentences of a language, and they must assign the correct meanings and phonetic properties to the sentences generated. The earliest model of Chomsky (1957) attempted to predict all and only the grammaticality or wellformedness facts of English and allowed for the generation of phonetic representations, but was not concerned with the assignment of meanings, in the form of semantic representations, to the syntactic strings generated. Not only was there no semantic component with the purpose of assigning such semantic representations – as there was in Chomsky (1965) – but it was further claimed that considerations of meaning were quite separate from the kinds of syntactic facts on the basis of which all and only the grammatical sentences of a language were to be predicted. Syntax was, therefore, autonomous and independent of meaning.

However, one of the most important and most general developments which characterises work in transformational theory since Chomsky (1957) has undoubtedly been the gradual inclusion of semantics into the model. Katz and Fodor (1964) proposed a semantic component whose purpose was to pair syntactic phrase markers with their appropriate semantic representations. And in the syntactic component itself semantic considerations came to play an increasingly important role. We shall summarise the landmarks in this gradual inclusion of semantics into Transformational Generative Grammar as a background against which to view the interaction between meaning and grammaticality prediction in definite and indefinite noun phrases.

Chomsky (1957)

In fact, even in Chomsky (1957) semantic considerations were not absent from syntax. From the beginning, the underlying syntactic structure has been a disambiguating level of representation, assigning to structures such as the shooting of the hunters distinct and semantically unambiguous structures (corresponding roughly to someone shoots the hunters and the hunters shoot). Chomsky claims (1957, ch. 8) that such examples of constructional homonymity constitute independent justification for a level of underlying structure linked to surface structure by transformational rules. (The term ‘transformational level’ is used at this stage to refer to this lower level of representation, the later term of Chomsky (1965) being, of course, deep structure.) And he uses the same type of argument as is used when justifying other significant levels of representation. He writes: ‘… a perfectly good argument for the establishment of a level of morphology is that this will account for the otherwise unexplained ambiguity of /ənəym/.’ (Chomsky, 1957, p. 86.) (The ambiguity being between a name and an aim.) And similarly,

… considerations of structural ambiguity can also be brought forth as a motivation for establishing a level of phrase structure. Such expressions as ‘old men and women’ and ‘they are flying planes’ (i.e. ‘those specks on the horizon are …’, ‘my friends are …’) are evidently ambiguous, and in fact they are ambiguously analyzed on the level of phrase structure. [Chomsky, 1957, pp. 86–7.]

Conversely, surface sequences which are quite distinct on the morphemic level may be identical on the level of phrase structure: Chomsky’s examples (p. 86), John played tennis and my friend likes music are both represented as NP–Verb–NP on the phrase structure level. The existence of sequences which are ambiguous and identical at a higher level and unambiguous and non-identical only at a lower level and conversely of sequences which are non-identical at a higher level and identical at a lower level, has always provided an important justification for the very validity of these levels as significant levels of representation. And the same argument is used by Chomsky again in further justifying a level of syntactic representation beneath the surface. The ambiguity of the shooting of the hunters is resolved at the lower level by being linked to two non-identical underlying structures. Conversely, there are many cases of non-identical surface structures with one and the same underlying structure (actives, passives, questions, negative sentences, etc.).

We have now found cases of sentences that are understood in more than one way and are ambiguously represented on the transformational level (though not on other levels) and cases of sentences that are understood in a similar manner and are similarly represented on the transformational level alone. This gives an independent justification and motivation for the description of language in terms of transformational structure and for the establishment of transformational representation as a linguistic level with the same fundamental character as other levels. [Chomsky, 1957, p. 92.]

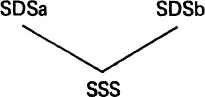

Figure 1.1 illustrates the mapping between underlying and surface structure for the shooting of the hunters. SSS refers to syntactic surface structure, and SDSa and SDSb to syntactic deep structures which are both semantically and syntactically distinct.

Figure 1.1

This same pattern has often been argued for on purely syntactic grounds in the transformational literature. For example, the sentences John is eager to please and John is easy to please are identical in syntactic surface structure and yet are generally derived from distinct underlying structures (corresponding to John is eager (for John to please) and it is easy (to please John)) on account of the syntactic differences between them.1 Yet it is clear from Chomsky’s quote (p. 92) that the existence of semantically ambiguous structures like the shooting of the hunters was considered to provide ‘an independent justification and motivation’ for an underlying syntactic structure beneath the surface, quite apart from the purely syntactic motivations for such a level, of the kind exemplified in note 1. And hence part of the justification for a level of syntactic structure beneath the surface has been semantic all along.

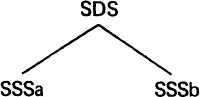

The converse state of affairs to that illustrated in Figure 1.1 can be seen in Figure 1.2, where one syntactic deep structure underlies surface structures which are syntactically and semantically different although related and hence similar in some respects, for example declarative and interrogative versions of the same underlying string, or positive and negative versions, etc.

Figure 1.2

Following Chomsky (1957) a large number of detailed studies were undertaken using the transformational method. Different deep structures were assigned in the case of constructional homonyms such as the shooting of the hunters and in other, probably most cases, syntactic arguments alone were used to justify proposed deep structures and transformations. By syntactic evidence transformationalists have always understood the facts of grammaticality and ungrammaticality provided by native speaker intuitions, i.e. the possible and impossible distributions of formal syntactic elements, grammatical morphemes. (The data in note 1 give an example of syntactic evidence.)

Ross’s Principle of Semantic Relevance

One rather surprising fact which was gradually to emerge in a very large number of cases was that the syntactic deep structures required on purely syntactic grounds turned out to be considerably more semantically specific and closer to the meaning than the corresponding surface structures. Since the arguments for the relevant deep structures were syntactic there was obviously no a priori reason why this should have been so. Ross (1972, p. 106) refers to the situation as the ‘principle of semantic relevance’: ‘Where syntactic evidence supports the postulation of elements in underlying structure which are not phonetically manifested such elements tend to be relevant semantically.’

One classic example of this principle is the imperative analysis. The grammaticality of

1.01 | Wash yourself. |

1.02 | Wash me. |

1.03 | Wash him. |

1.04 | Wash them. |

and the ungrammaticality of

1.01′ | *Wash you. |

1.02′ | *Wash myself. |

1.03′ | *Wash himself. |

1.04′ | *Wash themselves. |

can only be explained by postulating an underlying subject you for imperatives, which triggers reflexivisation of a second person object pronoun, thereby generating 1.01 and blocking 1.01′, and which disallows reflexivisation with non-identical pronominal objects, compare 1.02–1.04 with 1.02′–1.04′. This evidence is clearly syntactic, but the result is an abstract deep structure morpheme which is semantically relevant. For the speaker when issuing an instruction in the form of an imperative is not commanding himself or some third person to do something, but his addressee, i.e. precisely the person who is referred to by the you form.

Some other structures cited by Ross (1972) requiring a deep structure which is semantically more expressive than the corresponding surface structure are:

1.05 | Somebody wants my toothbrush. |

1.06 | Ed wins at poker more frequently than Jeff. |

1.07 | I promise you _ to anoint myself with Mazola. |

1.08 | I tried to write a novel and Fred _ a play. |

Ross notes that there exists syntactic evidence in all these cases which supports the postulation of semantically relevant elements in deep structure which are not present on the surface: a clause which I have in 1.05, a clause Jeff wins at poker (with some frequency) in 1.06, a subject NP I in 1.07, and a clause Fred tried to write a play in 1.08.

In our survey of the development of Transformational Generative Grammar we have so far found that semantic considerations led to the postulation of semantically unambiguous underlying structures in many cases and that purely syntactic arguments were found to support the existence in deep structures of many semantically relevant but non-phonetically manifested elements, which it is reasonable to assume would have to figure also in a semantic representation.

Katz and Postal (1964)

The next important development was the proposal in Katz and Postal (1964) that transformations should not change meaning. The effect of this proposal was essentially to rule out the kind of situation illustrated in Figure 1.2 above, i.e. cases of one single syntactic deep structure underlying two or more semantically different surface structures. Instead, each semantically distinct surface structure was assigned a different deep structure, i.e. Figure 1.2 became Figure 1.3 (where SSSa and SSSb are again semantically distinct syntactic surface structures). In such a system the transformations are meaning-preserving in the sense that they map unambiguous deep structures onto the surface forms which can actually carry the meanings assigned to these deep structures. They do not bring about an output with a meaning different from that of the deep structure input.

Figure 1.3

The Katz-Postal meaning-preserving hypothesis had no effect on derivations whose underlying structures were already unambiguous and could support semantic interpretation, as with the nominalisation examples the shooting of the hunters. Furthermore, it only applied to rules which were optional, for obligatory transformations had never changed meaning in the first place. There are basically two reasons for this. First of all, as Katz and Postal (1964, p. 31) point out, ‘the output of sente...