![]()

1

Income Measurement in Arab States

Thomas Stauffer

Introduction

This chapter addresses the question of measuring national income and national economic performance with particular reference to the Arab states of the Middle East. It indicates the adjustments to the existing national income accounts which are needed in order to obtain more meaningful measures of income which permit appropriate comparisons among the states of the area or with states elsewhere in the world.

The present system of national income accounting (SNA) involves accounting conventions which are not well suited to certain Third World economies. The concepts of national income accounting were originally evolved beginning in the late 1930s to meet the demands of the industrial economies of Europe and certain of the conventions and standards which emerged, while indeed appropriate for integrated industrialised economies, are much less appropriate for economies which are heavily dependent upon depletable resources, like oil, or where transfer of labour income looms large in the resource balance of the host or recipient economy.

Many — if not most — of the economies of the Middle East are characterised by an unusual degree of dependence upon nonrenewable assets, such as oil or phosphates, or upon unrequited transfers of foreign aid in the form of grants or concessional loans, or upon quasi-rents such as the income from remittances or emigrant labour or the locational rents of pipelines and canals.

The contribution of these unrequited resources or liquidations of capital (mineral resources) is so large, that the structure of the economies is dominated not by domestic factors of production but rather by the process of adapting to and incorporating the economic rents or external flows of resources.

There is no need for special income accounts for Middle Eastern states and the Arab states are not unique in receiving aid, portfolio income, or receiving or transferring labour remittances. These issues arise more generally in measuring income in countries as diverse as the United States, the Pacific island of Nauru, Lesotho and Switzerland. However, the sheer size of these flows in the case of many states and the relative magnitude of the requisite adjustments, dictate that the special aspects of these sources of income must be reflected more carefully in the construction of the national accounts and in the measurement of income.

The adjustments are indeed quite large for some countries. The national incomes of the oil exporters, which are the most egregious examples of the difficulties in measuring income, are overstated by factors of between two and five; i.e. the incomes, when corrected for depletion of the wasting oil asset, are between 20 and 40-odd per cent off the conventionally reported values. Conversely, the national incomes of states such as Jordan or the two Yemens, which benefit from sustained flows of workers' remittances, are understated by between 30 and 50 per cent.

The adjustments are also a prerequisite to interpreting economic affairs in these states and in particular are absolutely necessary in the case of many of these states with regard to three of the most important uses of income in analysing political-economic behaviour:

Comparisons of income

Rankings and comparisons of national incomes are misleading, without these adjustments, since the relative changes differ so markedly across countries.

Measuring dependence

The dependence of the economies upon resource rents, transient sources of income, unrequited transfers or debt accretion is not reflected in the standard measures of income.

Interpreting performance

Illusions of growth result when economies benefit from injections of rents or external resources and these effects must be separated out in order to assess the extent of self-sustainable growth.

In the following sections of this chapter we shall outline the sources of incomparabilities in interpreting national income, distinguish between static or technical adjustments and dynamic adjustments, and illustrate the effects of adjusting for the major sources of distortion in a select set of cases.

The second part develops a taxonomy of the rents and other sources of revenues which require special treatment in the measurement of national income or economic performance, indicating those where adjustment to the national accounts is necessary and those other sources, such as aid or locational rents, where the accounts need not be adjusted but where the income or GDP/GNP must be interpreted carefully.

Part three turns to the measures of economic dependence and the dynamic contribution of rents to income, sketching the mechanism of the 'rentier multiplier' and showing that rents and unrequited resources generally contribute more to reported national income than would appear even in the revised or adjusted national accounts, so that the extent of dependency is still greater.

The last part illustrates adjustments as applied to a number of Arab economies in order to highlight the different types of corrections and to show how the measures of both performances and dependency are sharpened.

Issues of Income Measurement

The measurement and interpretation of income for many of the states of the Middle East is complicated by those states' unusual degree of dependence upon special resources, i.e. economic rents, labour remittances, or foreign aid. In this and the following section we shall indicate how the national income accounts must be modified to include these effects or how supplementary measures must be introduced in order to characterise the economies.

In this section we shall present a taxonomy of the sources of revenue which require special treatment or interpretation and, for those three which require respecification of income — extractive rents, portfolio income, and workers' remittances — we shall indicate the adjustments to GDP or GNP which are needed.

Taxonomy of receipts

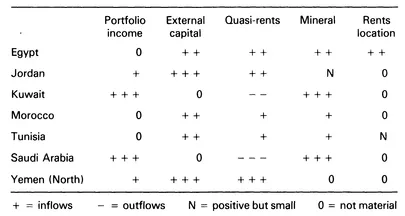

The array of 'special resources' is shown in Table 1.1, which lays out the taxonomy of special flows into or out of the major Arab economies of the Middle East. The impact and relative importance of each type of flow differs from country to country and will be discussed in the last part with respect to specific examples: here we shall pursue only the general features.

Table 1.1: Flows of rents and external resources: Arab economies of the Middle East

Extractive rents

The largest anomaly in measuring income in the Middle East results from the petroleum sector, since the production of oil is the liquidation of a finite asset, so that oil income must be interpreted much more carefully.

Conceptually, the same question arises with regard to all extractive industries, including phosphates which are important in several Middle Eastern countries. However, the share of rents in market value is very much less in all other mineral industries and the discussion hereafter will focus upon oil.

Oil revenues consist of two components: (i) the factor costs, i.e. the payments to the labour and capital involved in discovery, development and production of the oilfields; and (ii) the value of the finite resource itself.

Most of the price of oil in the Middle East consists of economic rent. Actual costs in the Middle East under current conditions are a small fraction of the market price of oil, so even in the case of high-cost oil between 80-85 per cent of the total revenues are indeed economic rents attributable to the generally favourable cost conditions in the Middle East and the high value of oil in energy markets. More typically, rents comprise 95-97 per cent of gross receipts (low-cost oil).

The difference between the value of the oil and the costs of production can be interpreted two ways. It can be viewed as a quasi-rent to the inframarginal producer or as a drawdown of the capital value of the finite stock of a depletable resource.

Locational rents

A second source of economic rent is that derived from the geographical advantage associated with pipelines and canals. Revenues from oil pipelines and canals loomed larger in the Arab economies in an earlier period when they were principal sources of foreign exchange receipts to Egypt and Syria.

In this case the rent is the difference between the transportation tariff or toll and the full costs of providing the services, where the latter are payments to factors of production. In contrast to the trend in oil rents, these locational rents have declined steadily because technology has eroded the cost advantages of the shortcuts.

Today locational rents are a major item only in the case of Egypt, where the gross receipts from the Suez Canal are about one-fifth of earned foreign exchange (excluding aid).

Portfolio income

Portfolio income in the form of receipts of interest or dividends is important in the Arab Middle East. This is in marked contrast to most areas of the Third World, where most countries are characterised by net outflows on interest accounts. A subset of Middle Eastern countries, the Arab oil producers of the Gulf, are large net investors and thus receive large net flows of investment income.

Moreover, for that set of countries — the larger oil exporters of the Gulf — portfolio income is large in relation to current levels of oil exports, so that it must be considered when measuring the economic resources available to the country.

This item is exceptional because it is positive and relatively large, whereas usually the adjustment to GDP for portfolio income is negative and relatively small.

Labour remittances

Labour remittances are large elements in the balance of payments of many Middle Eastern countries, such as Jordan, Egypt, or the two Yemens, which are net beneficiaries. In Arab states with large non-resident labour forces, their remittances flow in the opposite direction, as is the case for Kuwait, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

For the host countries remittances by expatriate labour are direct costs, but for the beneficiary countries there may be some element of economic rent in the receipts. In so far as the migrant worker commands a higher wage abroad than at home, his remittances are quasi-rents to the extent of the difference between the remittance amount and the net value added which the worker might have contributed had he remained at home.

Capital receipts

Capital inflows are important in certain states and contribute significantly to disposable national economic resources in a number of cases. These inflows take several forms: (i) borrowing; (ii) direct investment (relatively rare); (iii) unilateral transfers in the form of aid; (iv) drawdowns of foreign exchange reserves.

External capital sources in a number of cases provide such a large fraction of available resources th...