- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Henri Fayol, the Manager

About this book

Henri Fayol is one of the most important management theorists of the twentieth century. Guthrie and Peaucelle present a study of Fayol's management, comparing the theories set out in his book with his hands-on experience and practice. The first English translation of the third part of Industrial and General Management appears as an Appendix.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Henri Fayol, the Manager by Jean-Louis Peaucelle,Cameron Guthrie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 THE INDUSTRIAL CONTEXT: THE COAL AND STEEL INDUSTRIES IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE

DOI: 10.4324/9781315654546-2

Henri Fayol was the managing director of a mining and steel-making company from 1888 to 1918. The coal and steel industries were important motors of industrial development, and production increased over this period. It was a time of great technological advances, obliging industrialists to reinvest regularly. On a global scale, France was a modestly ranked producer.

The situation in France was characterized by a number of laws governing mining, and a strict state oversight of industrial activities both to levy taxes and ensure that security measures were taken to avoid disasters. Wages were freely set but remained low, although they doubled during the nineteenth century. As wages were higher in industry than in agriculture, labour was attracted to factories and mines and this was the main driving force behind peasant migration.

To better understand Henri Fayol’s actions, we present his company in 1898 after he had been managing director for ten years. It was a large company employing some 10,000 workers, but it remained of a modest size compared to others in the same industry. Schneider et Cie, for example, employed 10,000 workers on one site in the town of Le Creusot, and just as many at its other sites. It made comfortable profits in its four coal mines and four steel factories.

The Coal and Steel Industries in the Nineteenth Century

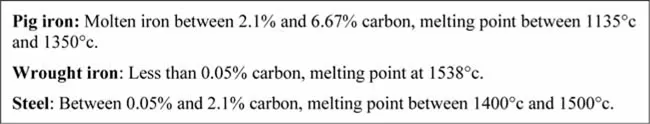

Man has known how to make iron for more than 3,000 years with iron ore deposits and mines spread throughout the world. Production increased significantly with the invention of the charcoal-fuelled blast furnace to produce pig iron that was used by the Chinese for around 2,500 years before it was introduced across Europe in the sixteenth century.

The English invented the modern steel-making process when they began heating blast furnaces with charcoal in the eighteenth century. The pig iron extracted from the blast furnace was transformed into iron by slow carbon oxidation which involved stirring the molten iron in a reverberatory furnace. This puddling technique was invented in 1784 by the Englishmen Peter Onions and Henry Cort, and was significantly improved by Joseph Hall in 1839.

In the early nineteenth century, the English industry was ahead of its time. French factories began using the English charcoal-based process in 1820, and they replaced charcoal with coke in 1840.

Two inventions then allowed steel to be produced in high volumes. In 1856 Henry Bessemer (1813–98) invented the Bessemer process that could rapidly process large quantities of metal. The process was adapted for phosphoric iron in 1877 by Sydney Gilchrist-Thomas (1850–85) and his cousin Percy Carlyle Gilchrist (1851–1935) using a basic refractory lining (Thomas-Gilchrist process). This allowed impure iron ores to be used, notably those from the Lorraine region in France.

Five years later, Carl Wilhelm Siemens (1823–83), a German-born British engineer, patented the regenerative furnace in 1861. The waste heat in the fumes from the furnace was fed back through a chamber containing bricks, heating it to a high temperature and then using the same path to introduce air into the furnace – the preheated air significantly increased the flame temperature.

In 1863 this preheating system was used by the Frenchman Pierre Emile Martin (1824–1915) in a furnace that slowly transformed iron into steel using iron ore and scrap iron. This open hearth process (known as the Siemens-Martin process) became widely used for special steels of precise composition. In 1867 Carl Wilhelm Siemens built a similar furnace, and in 1879 an engineer working with Henri Fayol by the name of Alexandre Pourcel adapted the furnace for phosphoric irons.

These successive inventions allowed for the production of greater quantities of iron and steel at lower prices. The steel industry became the main market for coal producers, followed by heating and gas lighting. Coal was the main source of energy prior to the use of petrol. By the end of the nineteenth century steel had essentially replaced iron, and iron works had to constantly invest to increase their capacity and modernize their tooling.

Growth over the period was dampened by several economic downturns. For example, during the Long Depression from 1873 to 1896 growth slowed and production dropped. Iron production in 1886 was 25 per cent lower than in 1883. The production cycles for the coal and steel industries were not, however, synchronized with the rest of the French economy. Economic fluctuations led mining and steel companies to accumulate large cash reserves, distribute dividends prudently and favour self-funded projects rather than opening their capital to new shareholders.

In 1830 30 million tons of coal was mined in Great Britain, representing 80 per cent of global production. The United States of America overtook the United Kingdom as the world’s main coal producer in 1900, and accounted for 500 out of the 1,216 million tons mined globally in 1913. Over this eighty-three-year period world production grew by 4.3 per cent per year, with 3 per cent growth in the UK and 8 per cent in the USA.1

The growth in iron production was similar to that of coal. In 1913 the USA produced approximately 30 million tons, which was three times that produced in the UK. With an annual average growth rate of 6.5 per cent, by 1890 the USA were producing more iron than the UK, where growth was only 3.5 per cent.

Steel was produced in large quantities starting in 1870. Production grew annually at a rate of 8 per cent in the UK and 15 per cent in the USA. By 1913 the USA was producing 30 million tons of steel, compared with 8 million tons in the UK. In 1900 the USA was the main producer of coal, iron and steel.

Germany also experienced a strong 6 per cent annual growth in coal and iron production from 1830 onwards, and a 12 per cent growth in steel from 1870. By 1913 German coal production was two thirds that of the UK, but the country produced 60 per cent more iron and twice as much steel. It was the world’s second producer of iron and steel.

France remained the fourth global producer of coal and iron. It accounted for 5 per cent of global coal production in 1830, and only 3 per cent in 1913, despite average annual growth of nearly 4 per cent. It was in a similar position for its iron and steel production which, despite increasing by 10 per cent from 1870 levels, was surpassed by Russia whose steel industry grew at the same 15 per cent per year rate as that of the USA.

The French coal, iron and steel industries were relatively small on a global scale. Activity around the Massif Central area (in central France) during the 1850s accounted for 57 per cent of total national production. The discovery of coalfields in the Nord and the Pas de Calais departments towards the end of the nineteenth century shifted the industry to the north-west of France, where it would later be exposed to World War I. By the 1890s, the Centre region only accounted for 32 per cent of national production.

The number of workers in the collieries grew as production levels increased. In 1888 105,000 workers were employed by the mines, of which two thirds worked underground. The numbers rose to 150,000 in 1898, and 200,000 in 1913.

Productivity in the French minefields was low due to difficulties in mining the relatively thin coal deposits. By comparison, in 1913 the 450,000-strong German mining workforce extracted 190 million tons, representing an output of 422 tons per worker per year, while in the same year 200,000 French workers only mined 41 million tons, representing an output of 205 tons per worker per year, at half of German productivity levels.

French production remained relatively low and always beneath its own needs. Coal was imported to meet 30 per cent of national consumption. Steel and iron products slightly exceeded local demand allowing some produce to be exported. France was a main importer of UK coal, accounting for 17 per cent of the United Kingdom’s coal exports between 1870 and 1904. Shipping costs were relatively low, in particular between Cardiff and Bordeaux, making up 40 per cent of sales price. Import duties increased prices by a further 5 per cent. British coal that arrived into the ports of Normandy, Brittany, the Atlantic and Channel coasts and even Marseilles was still 40 per cent cheaper than French coal, and also of superior quality. The British mines made healthy profits on their coal exports to France.2

French Mining Legislation

During the nineteenth century all industrializing countries adhered to the doctrine of economic liberalism. While companies could freely invest and sell their produce, laws and regulations differed between countries. France had mining laws that provided for oversight by a controlling body, the state Mines Service,3 which regularly visited each mine. Towards the end of the century, French mining legislation was used as a model for legislation in other industries.

Mining in France was governed by the Law of 21 April 1810 that distinguishes the ownership of the land on the surface by private owners from resources lying underground that belong to the state. Operating a mine involved obtaining the authorization of the state in the form of a concession and then paying annual royalties, which were calculated based on the surface area of the mine plus 5 per cent of profits. Mining companies had to negotiate with private owners either to acquire the land on the surface, or to pay for any damages to the land caused by mining activities.

This law was completed by a decree on 3 January 1813 that required the reporting of accidents, the monitoring of arriving and departing miners and the interdiction for children under ten years of age to work underground. These measures reflect the growing social preoccupations and pressures at the time. Mining laws were also progressively updated to limit the working day of young and female workers. When Henri Fayol became managing director, the law stated that women and children less than 12 years old could not work underground,4 the minimum working age was 8 years and the maximum working day was eight hours for children ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- List of Figures and Tables

- Introduction

- 1 The Industrial Context: The Coal and Steel Industries in Nineteenth-Century France

- 2 The Financial Function and Corporate Governance

- 3 Planning

- 4 Organizing: The Management of Managers

- 5 Organizing: The Management of Workers

- 6 Coordinating, Commanding, Verifying: Information Systems and the Accounting Function

- 7 The Commercial Function: Sales and Pricing

- 8 The Technical Function

- 9 The Security Function

- 10 Conclusion

- Appendix 1: The Third Part of Industrial and General Management

- Appendix 2: Henri Fayol's Final Interview

- Works Cited

- Notes

- Index