![]()

Chapter 1

Land and the Developed Economy

Is there a land problem? If so, what form does it take? Is the finite supply of land on the globe inadequate to support the present population? Or is there a land shortage only in a few countries or in some limited regions? Is land used in a way which represents its true value to the community? Or is shortage the consequence of inefficient operation of the land market, or of the power of landowners? More particularly, is it possible for a developed economy to suffer from a land problem?

Questions such as these are not new. Indeed, they have caused debate ever since Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population almost two hundred years ago. Nor will they be answered finally in this book, for it is too much to hope that after such a lengthy period of controversy any single view will command general agreement. The aim here is much more modest. It is to outline the major arguments for and against the proposition that land is in short supply, and that its use must therefore be carefully controlled; to examine the chief participants in land-use decisions which are made within systems of controls; and to describe land-use regulation in a selection of developed countries at the present time. In so doing it is hoped that the continuing debate about land will be better informed. It will not be concluded.

The land problem arises from two fundamental characteristics. In the first place it has long been acknowledged that land is in fixed supply, and that in this it differs from the other factors of production — labour and capital. For this reason some writers, and especially Malthus, have suggested that there is a limit to the population which the earth can sustain; and malnutrition and starvation in primitive societies have been seen as proof of such a proposition. But advanced economies are not constrained in this way. They can raise the productivity of land by means of chemical fertilisers and high-yield strains of crops. They can intensify its use through factory farming and cultivation in greenhouses. They can combat plant disease with insecticides, applied if necessary from aircraft; and thus they can raise farm output at a faster rate than that of population. Alternatively they can specialise in the production of manufactured goods and services, and use them to pay for imported foods. Thus they have the means of sustaining simultaneously very high densities of population and standards of living. Indeed, some developed countries face what appear to be endemic problems of agricultural overproduction; and many contain large tracts of both rural and urban land which have fallen out of use. On the other hand, the wide range of activities and types of production in affluent societies makes for a much more varied and expansive demand upon land than is the case in developing countries. High standards of living beget low densities of housing and sprawling urban settlements, which depend in turn upon the provision of extensive road systems. They give rise to demands for such land-consuming recreational uses as golf courses, and they are based upon extractive and manufacturing industries which are also major land users. Furthermore, many of these developments occur in areas which are used for agriculture, and especially in lowlands on which the soils tend to be of better quality. All this has led to widespread demands, even in the rich nations of the world, for the protection of prime agricultural land, and also of areas which are perceived to be of historical, scenic or scientific importance, from such developments.

Secondly, it is also generally appreciated that land is specific in location, that sites are immobile, and that as a result their character and value often owes as much to the use which is made of neighbouring sites as to their inherent qualities. Nuisances which spill over on to them may reduce that value, while the improvement of adjacent plots may lead to unearned, windfall increases in their market price. In the developed economy the scope for such spillovers is very great. Huge, coal-fired power stations affect not only the sites immediately next to them, but spread acid rain over thousands of square miles, to the detriment of both those who consume their electricity, and those who do not. Similarly, the filling and draining of wetlands or marshes may not only destroy rare wildlife habitats, but also increase the likelihood of flooding downstream. However, it is unusual for the costs of these losses to be met directly by those responsible for them. In other words, the market fails to allocate the costs and benefits of such operations accurately; and, because this is the case, there has been an increasing tendency for governments to restrict the rights of private owners to use their land as they wish, in the interests of society at large.

However, the argument has not been all one way. Voices have been raised against such interventions by governments. Some have echoed the views of Locke and Jefferson that land ownership makes the individual independent of the state, strengthens democracy and thwarts the abuse of government power; and they have noted how state ownership and control can lead to corruption and discrimination (Bjork 1980). Others have pointed to the failure of zoning and other planning devices to maintain farming in the urban fringe or to redevelop empty inner-city sites, to the expense involved in the drawing up and implementing of land-use plans and zoning restrictions, to the delays which are imposed on developers by the need to obtain approval before work can start, and to the drab uniformity of regulated development (Sharpe 1975, Strong 1981). Furthermore, the history of economic growth argues strongly for the private and unfettered ownership of land. Replacement of the communal organisation of land use under feudalism in Europe and Japan by private ownership conferred on owners the right to use their land as seemed most profitable, or to dispose of it to those who could use it more successfully, and opened the way to improvements in productivity which not only provided capital for investment in new manufacturing industries, but also food for the growing urban population working in those "industries. Some writers have even claimed that there is no foreseeable land shortage in the world, and many have suggested that Man is capable of using the earth's surface much more effectively than at present. In short, there is no agreement as to how best to manage the use of land, nor as to whether Malthus and his supporters will be proved right. Nevertheless, the issue is fundamental to any justification of land-use regulation, and therefore we shall examine the main arguments concerning both land shortage and market failure in Chapter 2.

Whatever the balance of the argument about whether or not land is in short supply or whether market failures are sufficient to merit intervention by the state, almost all developed countries have introduced some controls over land-use change during this century. As a result they have opened up the land-use decision-making process to a much wider range of individuals and organisations than would have been involved in a system based strictly on the market.

In this process central government usually articulates the needs of society as a whole, while local government is called upon to carry out much of the day-to-day administration of the central-government's policy. However, the perspectives and views of local and central authorities are rarely identical, and conflicts of interest arise between them. Furthermore, other interested parties are also able to press their points of view when public discussion replaces market decisions; powerful groups may be able to exert pressure on permit-granting authorities behind the scenes; and other, less influential bodies may react by disrupting public inquiries and by physically resisting the implementation of controversial proposals. In the absence of strictly-market decisions, land-use change will often be a compromise between the site owner, the developer, local and wider interest groups, and local and central government; and the result in any particular case will depend in large measure upon the relative strengths, and the degree of interest, of the various participants. In the most extreme case there is always the danger that regulatory agencies may become just as much the creatures of those who they are intended to constrain as market decisions are determined by those with most money. The success, or otherwise, of any system of control will depend in large part upon the extent to which it enables those without land to remedy the failings of the market. However, such groups often remain much weaker than those who they are opposing, in spite of the intervention of the state. We shall examine the general types of participant, or 'actor', who become involved when government seeks to influence land-use decision-making, and the relations between them, in the developed economy in more detail in Chapter 3.

However, all this presupposes that the definition of the 'developed economy' is clear, and that the identity of countries with such economies is known. It also suggests that, in all respects concerning land use and its regulation, all developed economies are similar. In fact, none of these conclusions would be correct; and therefore we must spend a little time discussing what is meant in this study by 'development', and showing why it will be necessary to examine the pattern of land-use regulation in not one, but several, different developed economies.

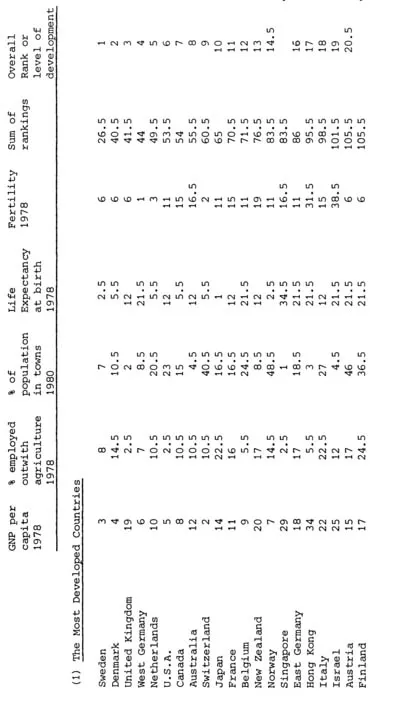

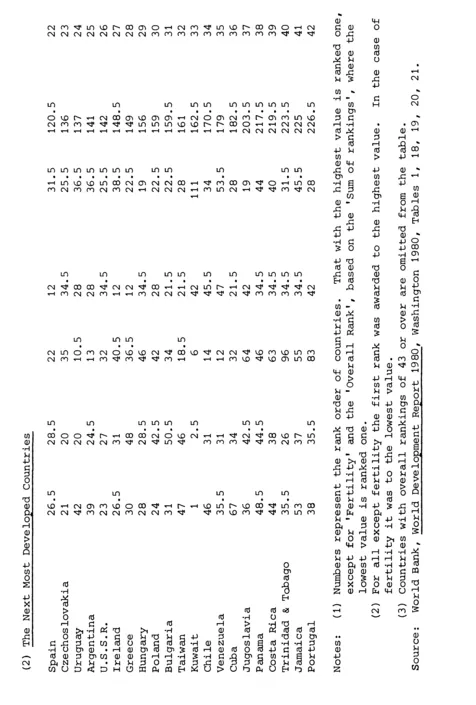

Many criteria have been used to measure the degree of development, and few have yielded exactly the same classification of the world's states. One of the most frequently employed has been Gross National Product per capita, but others have been the degree of urbanisation and the levels of literacy or infant mortality. Some of these have an important bearing on the land problem, but others are more tenuously connected to it. Some have been measured on a comparable basis for almost all countries, but information about others is difficult or impossible to acquire. In view of these difficulties an independent measure of development has been drawn up for this study based upon criteria which are available for all the countries listed in the World Development Report, and which are closely related to land issues.

Of these, Gross National Product per capita is one of the most important. Affluent nations make heavy demands upon land for housing and recreation —often having a large number of second homes — and for transport facilities. They can usually afford a high degree of mobility, either in the form of public transport or, more likely, the widespread private ownership of cars; and their populations have time to worry about such land-use issues as the preservation of historic landscapes or the habitats of rare fauna and flora, which are not directly or immediately related to their survival. Secondly, developed economies are, by definition, broadly based. They contain large secondary and tertiary sectors, and do not exhibit any narrow dependence upon primary forms of production. The country-to-town migration is largely complete, and a large proportion of the population lives in, or is in close contact with, the system of urban settlements. Indeed, 'getting out of town' is often more important to inhabitants of the developed economy than seeking 'streets paved with gold'. Thirdly, developed countries have high educational and medical standards. Rates of fertility are low, population growth is slow, levels of life expectancy are high, and population pressure on the land, at least insofar as it is directly linked with the threat of starvation, is absent.

Table 1.1: A Listing of Countries accroding to their Degree of Development

Each of the 125 countries listed in the Report has been ranked according to those of the three types of characteristics listed above for which information is available for all countries, and a composite index of development has been calculated by summing the scores for each country (Table 1.1). The countries have been divided into groups of twenty-one, so that each group represents one sixth of the countries considered. Those ranked one to twenty-one may be considered to have the 'most-developed economies', and those ranked twenty-two to forty-two the 'next-most-developed' in the world. Inspection of the list reveals the absence of a number of small countries which are not included in the Report. but which might have merited inclusion in the 'most-developed' sextile, such as Iceland and Luxembourg. It also shows that the classification is similar, but not identical, to those produced by some other studies of development. The countries in the 'most-developed' category are much the same as those recognised by the Pearson Commission (1969) and the World Bank as 'industrialised' or 'developed market economies', with the exception of South Africa, which is ranked forty-seven on the criteria and method employed to contruct Table 1.1. Countries in the 'next-most-developed' sextile are among the most prosperous of the 'developing countries' in those lists, and include all of the 'centrally-planned economies' in Europe with the exception of East Germany, which is in the first sextile, Albania and Romania. However, it should be noted that several of the Latin American countries included in this group are not normally considered to belong to the developed world. On the other hand, it is relevant to note that, according to one important measure of development — the supply of food as measured by calories per capita — these countries have all enjoyed a level of nutrition in recent years which has been equal to, or in excess of, that which is necessary, whereas many of those which do not fall into either the 'most-developed' or the 'next-most-developed' groups have suffered from inadequate food supplies (FAO 1982).

However, so...