![]()

Chapter one

An introduction to charities: what are they and how do they operate?

This book is about how charities work. From the perspective of organization theory (and by most definitions) a charity is a distinct and unusual form of organization. Why should millions of people in the Western world give money and gifts to charities? Donors never see their money again. They get apparently nothing in return, and in some cases most of the funds are used in a different country to support starving people in the Third World, for example. One answer is that human rationality can and often does embrace the concept of giving for moral, religious, or other motives. Altruism is a fundamental part of human rationality and altruistic behaviour is the foundation stone of very many charities in Britain and elsewhere in the world. Without unselfish regard for others, there would be no place for charitable organizations in our society.

Altruism accounts for one important stimulus to charitable activity and the spirit of self-help dominates much of the rest. As Smiles (1898) notes, man soon loses faith in systems and procedures which are guided and ruled by legislation. Man can often see no connection between his actions and the actions of organized institutions. Help from ‘without’ often enfeebles mankind, but self-help or help from ‘within’ encourages learning and invigorates (Smiles 1898: Chapter 1). The activities of most self-help groups are founded upon these principles and whilst these organizations are not legally classified as charities in Britain, their ethos permeates much of the concept and practice of charitable giving and charitable organization.

This book is the result of a study of a number of charities in Britain. The study concentrated upon how some of the large and increasing number of charities in Britain were managed. Charities in three areas of activity were examined, these being:

1. International agencies (including religiously based charities).

2. Charities dealing with the visually handicapped.

3. Charities performing sea-rescue.

How did these organizations decide to allocate gifts of money to particular projects? How did the managers of these organizations recognize that the time had come for a change in the level or the area of activities? Did such organizations develop along the lines of a consciously formulated strategy, or did they muddle through, tackling problems one at a time in a piecemeal fashion? How was the organization itself organized? Was the design of the organization a help or a hindrance to its activities? Did the charity appear to be efficient in using and allocating resources? All these and other questions were the stimulus for this book.

Before we embark upon the details and the findings of the study, it is first of all necessary to examine some of the very special and possibly unique constraints and opportunities which face the managers of charities. It might be argued that management is pretty much the same in its fundamentals in any kind of organization. But that is not wholly the case for the management of charities.

Whilst there are a number of similarities between the roles of chief executives in Shell or ICI and the directors of major charities such as Oxfam or the National Trust, the context in which they operate is, in many respects, dissimilar. This is true not only of the present context, but is also true of the genesis and the history of the charitable sector which bears a heavy hand on current strategies, developments, and management practice. We shall examine the major features of these contexts in the next sections.

The gift relationship

Managers of charities must take into account their role as ‘brokers’ alongside their other professional management activities. This is because the charity acts as an intermediary between givers (of money and other resources) and receivers of services (beneficiaries) who are often remote in time and in place (see Figure 1.1). This is the ‘gift relationship’ described by Marcel Mauss (1954) who looked at the concept of the gift in remote Polynesian societies, and elaborated by Richard Titmuss (1970) with respect to the voluntary giving of blood in Britain. During this study, 3,325 blood donors were asked the question: Why did they first decide to become a blood donor? The answers were then coded into the following categories:

1. Altruism (26.4 per cent of answers), e.g. a general desire to help people or society, or to help medical research especially for babies.

2. Response to appeals from the Blood Transfusion Service (18 per cent of answers).

3. Personal appeal, e.g. from a friend to give blood (13.2 per cent of answers).

4. Reciprocity, e.g. a repayment for a transfusion received in the past (9.8 per cent of answers).

5. Continuation, e.g. of people who started donating blood during World War 2 (6.7 per cent of answers).

6. Awareness of the need for blood, e.g. having witnessed an accident or a stay in hospital (not themselves needing blood) (6.4 per cent of answers).

7. Defence services, e.g. since 1945 a group in the military who experience pressure to donate blood. Often rewarded by 48-hour passes (5.0 per cent of answers).

8. Duty, e.g. through moral or other feelings of duty (3.5 per cent of answers).

9. To obtain a benefit, e.g. to discover blood group or a health check (1.8 per cent of answers).

10. Gratitude for good health, e.g. people who had experienced good health all their lives and viewed donating blood as a form of repayment (1.4 per cent of answers).

11. Donor belonged to a rare blood group, e.g. hence felt a particular responsibility to give blood (1.1 per cent of answers).

12. Miscellaneous (5 per cent of answers).

Figure 1.1 The gift relationship

Although altruism was listed as the largest category, other reasons for giving blood (nearly 74 per cent of the responses) are a hotch-potch of often unrelated reasons. The psychology of giving is a complex matter. Managing a charitable organization to attract individuals to give thus becomes a task of intricate complexity and of crucial importance since organizational survival is certainly at stake. Without a regular supply of givers, most charities will not survive. A manager of a charity cannot take the decision to change a supplier in the same way as can a manager in the profit-making corporate world (Hickson et al. 1986). Managing the gift relationship must take primacy in charities since all other activities stem from the receipt of resources.

Resource giving can take three main forms:

1. Goods-in-kind (of which blood is an example) can be given to the charity. Blankets, clothing, newspapers, bottles are other examples, which are often organized at the local level (e.g. a scout group). These are notoriously difficult to quantify and we are not aware of any study which has done so.

2. Giving time, which ranges from the time given by the armies of collection-box rattlers to the highly skilled, and often dangerous, work carried out by lifeboat men, mountain rescue teams, or field workers in the often politically unstable Third World.

3. Giving money; although this is still difficult to quantify precisely, it is much easier than the other two kinds of giving. Recent studies by the Charities Aid Foundation and the Institute of Fiscal Studies, London, assess the total amount of money given to British charity as around 5 per cent of the Gross National Product.

Saxon-Harrold et al. (1987) reveal that charitable giving in Britain per adult earning a weekly income of up to £80 is about £10 per week (at 1980 prices). Thereafter, giving money rises fairly steeply to a plateau of about £30 per week at a weekly income of £120. Plotting giving against age gives a V relationship with the lowest incidence of giving at the 40-year-old mark (approximately). Younger and older than this reflects increasing generosity. Presumably, the greater family and financial commitments of the 40-year-old head of household reflects the drop in charitable giving.

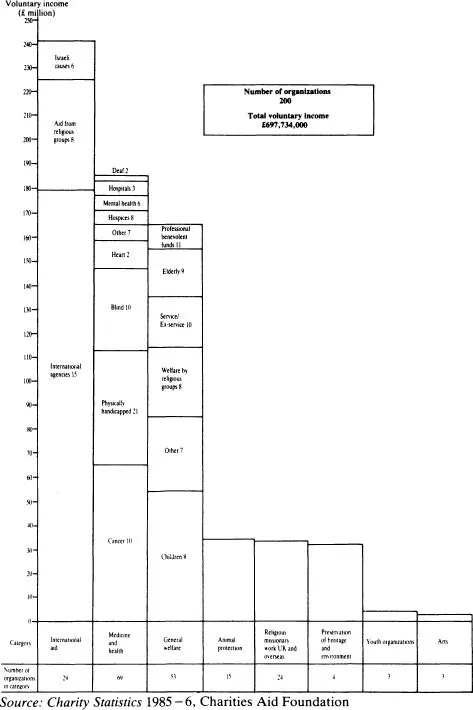

Our measure of the extent of charitable giving is taken from eight years of figures from the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF). This gives the total overall income and the total voluntary income of the top 200 charities classifies as ‘Grant Seeking’ by CAF.

Both total income and voluntary income of the top 200 charities has been rising on average by 30 per cent and 27 per cent respectively per year when the Gross National Product of the British Economy (GNP) has been rising at a lesser rate. In 1984, the voluntary income alone of the top 200 charities was 4 per cent of GNP.

Figure 1.2 Voluntary income of the major sectors (the top 200 charities)

The figure will certainly be an underestimate of the proportion of wealth given by the British people, since it excludes giving in kind and the giving of time. Also, of course, it only includes figures for the top 200 charities in Britain. There are around 150,000 registered charities, which goes some way to explain the slight variation in the figures given by various sources such as the Institute of Fiscal Studies and the Charities Aid Foundation. In addition, there is a smaller number of voluntary organizations which are non-registered charities (such as Amnesty International and a host of self-help groups) which do not appear in the figures and the income for these charities is difficult to assess with any precision. Of the registered charities in Britain, however, the top 200 account for the overwhelming majority of voluntary income.

Figure 1.2 shows the voluntary income of the top 200 charities broken down by sector of operation. Data are also given on the number of charities which operate in the sectors.

The largest category is medicine and health, covering issues such as cancer relief, physical and visual handicaps, heart disease and related problems, and the deaf. Over half the voluntary income in this category is accounted for by the cancer and physically handicapped sectors of activity.

The other big categories are general welfare (where children’s charities account for much of the income) and International Aid, in which the secular international agencies (one of the industries studied in this book) represent the biggest group. If nothing else, this table dispenses with the notion that the British care more for their animals than their people, since animal protection charities only account for around 5 per cent of total voluntary income. Cynics, however, may still argue that this is about the same level as voluntary contributions to the charities which care for the elderly.

Becoming a legally defined charity

There is no legal definition of a voluntary organization, but there is a relatively precise and strictly enforced definition of a charity. As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, mutual self-help groups are not considered to be charitable in the eyes of the Charity Commissioners who decide upon the question of charitable status. It would be wrong to assume that no ambiguity surrounded the definition of a charity. This has been a substantial issue which has been debated long and hard by the Charity Commissioners, the National Council for Voluntary Organizations (NCVO), the Wolfenden Committee (1978), and many others. Precise legal details can be found in Chesterman (1979) and Gladstone (1982).

It is sufficient for our purposes here to note that becoming registered as a charity endows sizeable fiscal benefits to the organizations. These take the form of various tax concessions which are thus made available. Although the Inland Revenue does not automatically concede tax advantages to legally registered charities, more than 90 per cent of currently registered charities enjoy exemption from income and corporation taxes. As Chesterman (1979) notes, charity law can be quite accurately described as little other than a sub-set of tax laws with little concern for anything else. To reinforce this point, the range of fiscal liabilities from which registered charities are exempt has grown progressively wider in recent years and the real value of exemptions has increased as the taxes levied upon non-charitable organizations has increased. The levels of capital gains tax and corporation tax have increased substantially over the last fifteen years or so, as have the taxes levied on those who donate or bequeath monies to organizations which are not registered charities.

Becoming a legally registered charity also means that the organization can set up an independent trading company which is exempt from a similar range of tax liabilities providing that trading profits are directed solely toward support of the original, primary charitable purpose of the organization. Well-known trading companies of registered charities include Oxfam’s retail outlets, mail order and greeting card operations, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children’s mail order and card service, and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution’s trading company which runs souvenir, gift, and Christmas card sales.

The laws of charitable trusts are an important division of the law of Equity. They are complex and ancient laws. Some are based, for example, on the transfer of property to descendants (Quia Emptores, 1290) or to the Church (Mortmain Statutes, 1300–1391). Three Acts also underpin the law of charitable trusts. The Charitable Uses Act of 1601 provides a framework for the gradual evolution of the legal meaning of charity. The Charitable Trusts Act of 1853 was a fine tuning of the previous Act, whilst the Charities Act of 1960 was definitive in requiring the introduction of a register of charitable organizations and in introducing the compulsory registration of charities.

There are four essential pillars of what is, in law, considered a charitable activity: education, relief of the poor, the advancement of religion, and other services which are considered in general to be beneficial to the community. The trustees of the organization must not benefit in any way from the organization and the beneficiaries cannot be those who give (hence the reason that self-help groups are excluded).

There must be some indication of ‘public good’ in the services offered (i.e. a number of people could benefit, not just a select few) and the organization must not be political or ideological, or both. This means that political parties or trade unions cannot be registered charities. Neither can most professional associations since they exist to benefit their members (although there are exceptions as we shall see) and pressure groups cannot be charities if their aim is interpreted as trying to effect changes in the law.

There is currently growing concern over the implications of these laws as being too restrictive and as being in the interests of the Charity Commissioners and others at the expense of organizational flexibility and change (Wilson 1984). There is also criticism that the law is not up to handling the range of current problems and issues which face modern voluntary organizations. For example, an organization such as Oxfam, which is a registered charity, may relieve suffering in all parts of the world. This activity is considered charitable and finds its roots in religiously based nineteenth century social philosophy. However, an organization which pressures for changes in what are considered to be the causes of poverty and suffering would be refused charitable status. Current management in Oxfam recognizes that strategic development of the organization must to some extent be aimed at attacking and addressing the issues of cause rather than be wholly a reactive charity to disaster when it strikes. Yet this is likely to bring the organization into conflict with the Charity Commissioners who would deem such activities to be uncharitable in their terms.

Similarly, the rather dated and rigid charity laws have brought organizations such as the Amnesty International Trust into conflict with the Charity Commissioners. Amnesty International is not legally a charity. Charitable status was refused in 1978 and again in 1981 when Mr Justice Slade argued that two of the organization’s objectives were political and could only be achieved by changes in the law or the administration of the countries...