![]()

1 Conceptual Approaches to Stereotypes and Stereotyping

Richard D. Ashmore

Frances K. Del Boca

Livingston College, Rutgers-The State University

This volume presents an analysis of stereotyping and intergroup behavior from a cognitive perspective. While no single unified theory is articulated, the authors of the chapters that follow do share a cognitive orientation. The purpose of the present chapter is to place this orientation within the context of other social scientific approaches to the study of stereotypes. Three separate, yet highly interrelated, aspects of stereotype research and theory will be examined. First, a history of the stereotype concept is presented. Here we discuss the significant events and trends of the past that condition present and likely future efforts in this area. Second, the various meanings ascribed to the term stereotype are considered. Implicit as well as explicit and operational as well as conceptual definitions are reviewed in order to explicate both areas of agreement and disagreement regarding how the construct "stereotype" is best defined. Finally, we discuss the basic orientations taken by social scientists in seeking to understand stereotypes. Although not sufficiently explicit or complete to be called "theories," three perspectives are clearly discernible—sociocultural, psychodynamic, and cognitive. The elements and implications of each of these three orientations are described.

History of Stereotype Research and Theory

The word stereotype was coined in 1798 by the French printer Didot to describe a printing process involving the use of fixed casts of the material to be reproduced. Approximately a century later psychiatrists began to use the related term stereotypy to denote a pathological condition characterized by behavior of "persistent repetitiveness and unchanging mode of expression [Gordon, 1962, p. 4]." It is important to note that psychiatry adopted the word "stereotypy," not "stereotype," and that stereotypy referred to fixity of behavior, both topographically (i.e., "unchanging mode of expression") and temporally (i.e., "persistent repetitiveness"). The related notions of "fixed," "unchanging," and "persistent" point to one of the major themes, usually referred to as "rigidity," in stereotype research and theory.

It was not until 1922 and the publication of Lippmann's Public Opinion that the term "stereotype" was brought to the attention of social scientists. That Lippmann is the father of "stereotype" as a social scientific concept is acknowledged in all historical accounts (cf. Brigham, 1971; Cauthen, Robinson, & Krauss, 1971; Fishman, 1956; Gordon, 1962; Jones, 1977; LaViolette & Silvert, 1951) and is indicated by the clear recognition accorded him in the earliest research reports on this topic (e.g., Katz & Braly, 1933; McGill, 1931; Rice, 1926). Perhaps because he was a journalist and not a scientist, Lippmann did not provide a single explicit definition of "stereotype." He did, however, set forth a number of ideas regarding stereotypes. These ideas are reflected in later conceptualizations and many seem startingly contemporary.

Certainly the most often quoted phrase from Public Opinion is "pictures in our heads." This phrase is the second half of the title of Chapter 1, which begins, "The World Outside and the...." It is here that Lippmann presented his basic thesis: Humans do not respond directly to external reality (i.e., "the world outside") but to a "representation of the environment which is in lesser or greater degree made by man himself [p. 10]." He called this a "pseudoenvironment" or "fiction." Lippmann assumed that "reality" was too complex to be fully represented in the individual's "pseudo-environment" and argued that stereotypes serve to simplify perception and cognition. In essence Lippmann used the term "stereotype" very much as contemporary cognitive psychologists use the term schema (e.g., Neisser, 1976), and social psychologists use the term social schema (cf. Taylor & Crocker, 1981). Although a variety of definitions have been proposed, most researchers would probably agree that a schema is a cognitive structure that influences all the perceptual-cognitive activities that together are labeled "information processing" (e.g., perceiving, encoding, storing, retrieving, decision making) with respect to a particular domain. For Lippmann, in other words, stereotypes were cognitive structures that help individuals process information about the environment: "This is the perfect stereotype. Its hallmark is that it precedes the use of reason; is a form of perception, imposes a certain character on the data of our senses before the data reach the intelligence [1922, p. 65]."

Lippmann did not, however, conceive of these cognitive structures as neutral. A whole chapter was devoted to the topic "Stereotypes as Defense." The theme of this chapter is captured in one simple sentence: "The systems of stereotypes may be the core of our personal tradition, the defenses of our position in society [p. 63]." Thus, stereotypes were cognitive structures that were integral parts of the individual's personality and served to explain or rationalize her or his social standing. With regard to this latter point it is significant to note Lippmann's description of Aristotle's first book of Politics: "with unerring instinct he understood that to justify slavery he must teach the Greeks a way of seeing their slaves that comported with the continuance of slavery [p. 64]." Other authors have offered similar explanations of stereotypes as societal-level phenomena—stereotypes explain the relationship between social groups (cf. Ashmore & Del Boca, 1976). For example, in slave-holding societies, the slave is generally depicted as "childlike" and, thus, his subservient position is best for master, slave and society.

While Lippmann was most concerned with explicating the role of stereotypes in shaping public opinion, he did make one suggestion regarding how these cognitive structures are acquired: "In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture [p. 55]." Thus, according to Lippmann, individuals do not necessarily develop stereotypes through some approximation of the slow and effortful process of scientific hypothesis testing. Rather, they frequently incorporate, as part of their way of cognitively organizing the world, the "folkways" of their cultural group.

Most of the major themes of later research and theory are evident in Lippmann's discussion of stereotypes. Of particular importance, he presented the basic themes of the three orientations to the study of stereotypes discussed in the concluding section of this chapter. The cognitive perspective is clearly foreshadowed by Lippmann's distinction of "pseudo-environment" from "environment" and his emphasis on how stereotypes simplify the environment to make it more psychologically manageable. Although he did not accept the Freudian underpinnings of what later became the psychodynamic position, Lippmann did see stereotypes as related to personality or identity and as serving "defensive" functions. Lippmann also anticipated the sociocultural orientation by: (1) suggesting that stereotypes rationalize existing societal arrangements; and (2) pointing to society as the source of many of our individual "pictures in the head."

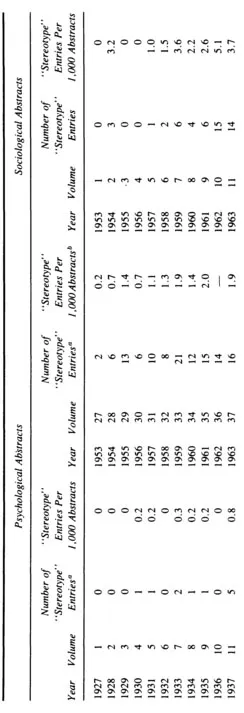

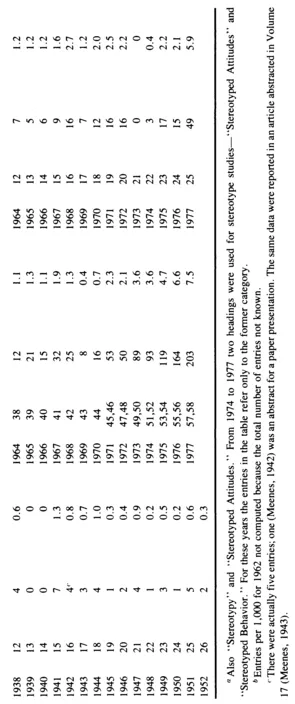

How did this rich conceptualization influence social scientists? As a partial answer, we have indicated in Table 1.1 the number of articles and books concerned with stereotypes that have been abstracted in the Psychological Abstracts from its inception in 1927 to 1977. As Table 1.1 suggests, Lippmann's immediate influence was not great.1 From 1927 to 1933 the term stereotype appeared only three times in the Psychological Abstracts: McGill (1931), Litterer

TABLE 1.1.

Number and Rate of Stereotype Entries Appearing in Psychological Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts Per Year

(1933), and Meltzer (1932). Inspection of these articles reveals three other relevant sources (Rice, 1926, 1928; Rice & Waller, 1928). All of these early investigations—except that by Meltzer (1932), which was concerned with "stereotypy" as a psychiatric or clinical phenomenon—shared a common conceptualization: If stereotypes are "pictures in the head" that shape perception of reality, then they must aid individuals in recognizing members of various social groups. And this shared conceptual approach gave rise to a common methodology: Photographs of individuals were presented to subjects who were asked to guess the occupations of the persons depicted. Evidence of stereotypes was of two types. First, stereotypes were assumed to exist if the perceivers were correct more often than would be expected on the basis of chance. Second, even when subjects were not accurate, their responses were said to be "stereotyped" when there were above-chance levels of agreement regarding the occupations of the pictured individuals.

While Lippmann introduced the concept to social scientists, it was Katz and Braly (1933) who conducted the classic empirical study of stereotypes. Princeton undergraduates were given a list of 84 trait adjectives (e.g., brilliant, neat, physically dirty) and asked to indicate those items that were "typical... characteristics" of each of 10 different ethnic groups. The stereotype of each group was operationally defined as the set of adjectives most frequently assigned to that group. For example, the stereotype of Turks included cruel (54%), very religious (30%), treacherous (24%), and sensual (23%). The adjective checklist procedure and the aggregate analysis introduced by Katz and Braly have served as the model for the majority of stereotype studies conducted since 1933.

Although not so explicitly, Katz and Braly (1933) had a significant impact on two other aspects of social scientific approaches to stereotypes. First, in discussing their results they noted the parallel between the stereotype of certain groups as revealed by the checklist procedure and: "the popular stereotype to be found in newspapers and magazines [p. 285]." This connection, plus the use of agreement or consensus to define stereotypes, suggests that stereotypes were considered to be, in large part, sociocultural or group-level phenomena.

Second, Katz and Braly linked stereotypes to attitudes and prejudice. The introduction to their article is concerned almost exclusively with attitudes and prejudice; the word "stereotype" occurs only once and even then does not refer to a set of beliefs about the characteristics of a particular group. The stereotype-prejudice connection was further developed in a second article entitled "Racial Prejudice and Racial Stereotypes" (Katz & Braly, 1935). This paper is concerned primarily with prejudice; stereotypes were analyzed only in terms of their implications for the evaluation of ethnic groups. In their final sentence, Katz and Braly (1935) virtually equated stereotypes and prejudice: "Racial prejudice is thus a generalized set of stereotypes of a high degree of consistency which includes emotional responses to race names, a belief in typical characteristics associated with race names, and evaluation of such traits [pp. 191–192]."

Allport (1935) further established the prejudice-stereotype link in his classic chapter on attitudes:

Attitudes and Prejudices or Stereotypes. Attitudes which result in gross oversimplification of experience and in prejudgments are of great importance in social psychology. . . . They are commonly called biases, prejudices, or stereotypes. The latter term is less normative, and therefore on the whole to be preferred [p. 809].

He also clearly articulated the view that stereotypes are bad. While this is implied in associating the term with prejudice, Allport specified some reasons why stereotypes might be regarded as bad. As is clear in the previous quote, he felt that stereotypes are oversimplified and thus to some extent incorrect. Further, stereotypes were considered to be rigid, and they were thought to impair perception and cognition.

The connection established between stereotypes and prejudice, in conjunction with the introduction of the adjective checklist, significantly altered the character of stereotype research in the years following the publication of Katz and Braly's (1933, 1935) articles. As indicated by Table 1.1, there was a small but steady stream of stereotype studies in the late 1930s and in the 1940s. Whereas some of these were concerned with stereotypy and stereotyped behavior as phenomena in clinical and experimental psychology, most dealt with stereotype as a social psychological construct. Unlike the earliest studies, however, racial, ethnic, and national groups were the major targets used in research. Verbal group labels (e.g., "Germans") replaced pictured individuals as stimuli and the adjective checklist became the major response format.

In 1950, Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford published The Authoritarian Personality. In this monumental two-volume work, they set forth a psychodynamic theory of prejudice. According to this theory, negative intergroup attitudes are rooted in a particular personality syndrome that is labeled the antidemocratic or authoritarian personality. One component of this syndrome is "stereotypy" or the tendency to think in terms of rigid, black-and-white categories. By implication, stereotypes are rigid beliefs about social groups. This certainly is not inconsistent with the position articulated by Allport. Adorno and his collaborators, however, provided an explanation for rigidity-prejudice and its attendant stereotypes fulfill a personality need.

The Authoritarian Personality generated a great deal of research (cf. Kirscht & Dillehay, 1967); however, it did not affect significantly either the amount or the nature of research on stereotypes. As can be seen in Table 1.1, the rate of stereotype publications remained relatively constant during the early and mid-1950s. The methods used to study stereotypes and the questions addressed in research also changed little. Indeed, Gilbert's (1951) well-known replication of the original Katz and Braly (1933) investigation at Princeton, published just one year after The Authoritarian Personality, typifies the stereotype research conducted at this time.

The rate of stereotype publications increased slightly in the late 1950s and remained relatively stable in the 1960s. This pattern is evident in both the Psychological Abstracts and in the Sociological Abstracts, which was first published in 1953 (see Table 1.1). Inspection of the empirical studies published during this period indicates that psychologists continued t...