![]()

A GAME OF FAIR DIVISION

A chap out of the Illinois River, with a little stern-wheel tub, accosts a couple of ornate and gilded Missouri River pilots:

“Gentlemen, I’ve got a pretty good trip for the up-country, and shall want you about a month. How much will it be?”

“Eighteen hundred dollars apiece.”

“Heavens and earth! You take my boat, let me have your wages, and I’ll divide!”

--Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi

1. INTRODUCTION

The “divide and choose” method has played an important role in the literature on fair division.1 This technique for allocating bundles of goods seems impartial, requires little cooperation from agents, and is nearly free of administrative costs. It is therefore somewhat puzzling that it has found so few applications in the real world, where sometimes even prolonged and costly negotiations produce only imperfect agreements. Either the method has drawbacks not yet well understood, or it is underutilized. This essay examines the game that arises when two agents agree to use the divide and choose method. The analysis leads to a resolution of the puzzle mentioned above, and identifies a class of situations where replacing conventional arbitration procedures with the divide and choose method can be strongly recommended.

In the sequel, an agent who would prefer another agent’s bundle of goods to his own will be said to envy the other agent. An allocation at which no agent envies another will be called a fair allocation.2 A well-known property of the two-person version of the divide and choose game3 is that each player can insure that he does not envy the other. The divider (D) can accomplish this by dividing so that he is indifferent to his opponents choice; the chooser (C) need only choose his most preferred bundle after D divides. That the players, acting together, can insure that the outcome of the game is fair is interesting, but more information about the allocations actually generated by the game is needed to judge its usefulness as a fair division device. Conceivably, with players motivated by self-interest, the game could generate an unfair allocation in spite of the above result.

To learn more about the divide and choose method, I assume that players seek to obtain the most desirable bundle possible. They are also assumed to behave noncooperatively, since negotiating a mutually acceptable settlement would be relatively easy if they were willing to cooperate, and the method would then be superfluous. In Section 2 of this essay D’s problem is formulated and his optimal noncooperative strategy is characterized. As is suggested by Luce and Raiffa [6, p. 365] and Singer [9], the common belief that D should divide the bundle so that he is indifferent about C’s choice is false. If D knows C’s preferences with certainty, under very general conditions -- roughly, that players’ behavior can be described by the maximization of continuous and strongly monotonic utility functions and that goods are homogeneous and perfectly divisible -- his optimal strategy involves dividing the bundle so that C is indifferent about his choice.

Once D’s optimal strategy has been characterized, several interesting conclusions follow. Luce and Raiffa’s belief [6, pp. 364–365] that the allocations resulting from this game are always Pareto-efficient is false. However, the noncooperative equilibrium of the game is a fair allocation and, under an additional mild behavioral assumption, is an efficient point in the set of all fair allocations. Luce and Raiffa’s statement [6, p. 365] that the role of divider is an advantage in the game if preferences are known is formalized and proved, and the allocation resulting from the game is shown to treat agents less equally than an equal-income competitive equilibrium (EICE) allocation.4 When both agents have identical preferences, however, the Pareto-inefficiency, divider’s advantage, and unequal treatment all disappear, and these results are robust in the sense that if agents have nearly identical preferences, nearly equal treatment and near-Pareto-efficiency result. Section 2 is self-contained, and the. reader who has more faith than time may wish to read only Section 2 and Section 5, which includes a summary of the generalizations of Section 3 and 4.

In Section 3, all but one of the pure-trade results (the one that establishes the relationship between game allocations and EICE allocations) are generalized to the case where production is possible -- that is, where each agent is endowed with productive resources that may either be consumed directly or used to produce other consumption goods. In this context, D plans the operation of the economy -- required factor supplies, production levels, and consumption shares -- and C then chooses which of the two roles in the economy he will assume.

In Section 4 the analysis is carried out in the case where the divide and choose process is followed by cooperative trade that both players anticipate in their strategy choices. Some of the results, notably the existence of dividers advantage, go through in this case. Finally, Section 5 discusses several possible further generalizations that would be of interest,

summarizes the results obtained, and considers their implications.

2. THE PURE-TRADE DIVIDE AND CHOOSE GAME

Assume that two persons have agreed to share a fixed bundle of homogeneous and perfectly divisible goods by the divide and choose method, and that their roles have already been determined in some way, perhaps by the toss of an unbiased coin. Each person behaves noncooperatively, seeks only to obtain the most desirable bundle possible, and has preferences that are representable by a continuous and strongly monotonic5 (though not necessarily quasiconcave) utility function. In addition, D is assumed to know C’s preferences with certainty, which is not a completely natural assumption to make in most situations. But studying the certainty case permits clearing up an area of confusion in the literature, provides a necessary preliminary to a more general analysis, and may serve as a reasonable description of some situations. Finally, an innocuous assumption is included to simplify the exposition. Whenever C is indifferent between the two bundles offered him he can be counted on to choose the one that D would prefer him to. Since it has already been assumed that C’s preferences are known with certainty, this assumption is innocuous -- a tiny adjustment in D’s division could induce C to make the desired choice without perceptibly altering either player’s consumption or welfare. This assumption allows us to deal with maxima instead of suprema, and greatly simplifies the statements of some of the results.

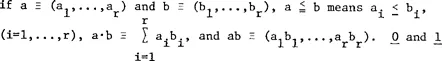

In the sequel, the following vector notation is used:

denote a vector of zeros and a vector of ones, whose dimensionalities should be inferred from the context.

Units are chosen so that the vector of goods to be allocated is 1. A division by D will be represented by the m-vector z, indicating that C may choose between the consumption bundle z and its image 1-z. Let UD and Let UC be D’s and C’s utility functions, and assume without loss of generality that z is the bundle D intends for himself. Then D’s optimal noncooperative strategy in the game is any solutio...