![]()

1 Reinventing the “American dream”

Four waves of post-1978 Chinese student migration

During his state visit to the United States in February 2012, the then Chinese vice president Xi Jinping scheduled a visit to the city of Muscatine in Iowa. It was for a special meeting with the American host family he stayed with in 1985 when he participated in an agricultural research trip as a provincial government official.1 While the 2012 visit was largely a strategy of public diplomacy to construct a positive and personable image of Xi, who was scheduled to take the top Chinese leadership the next year, it reflected the long history of Chinese visiting and studying abroad (particularly in the United States) since the mid-nineteenth century in hopes of developing China into a modern nation. It also represented the flourishing educational and cultural exchanges between China and the United States in the first years after the normalization of US–China relations in 1979.

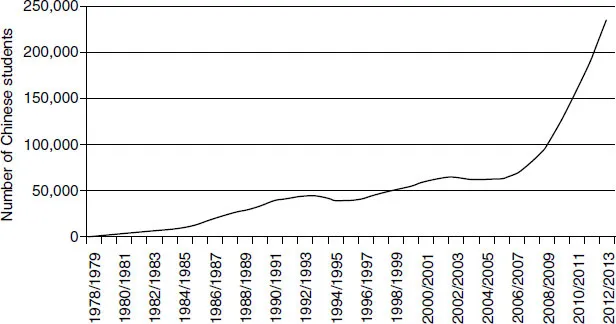

The movement of Chinese studying in the United States has continued since the late 1970s and in fact has gained new momentum in recent years. China became one of the top sending countries of international students in the United States after the mid-1980s, and the recent skyrocketing number of Chinese students in the United States further secured China’s position as the number one sending nation after 2009. Chinese students now comprise more than a quarter of all international students in the United States.

This chapter studies the four major waves of Chinese students studying in the United States after China’s reform, examining the shifting patterns along with the changing US–China relations and the transformation of both societies. Scholars have documented the first two waves from the start of the reform to the early 1990s in detail, obviously due to the significant historical contexts of the normalization of US–China relations in the 1970s and of the Tiananmen Square Incident in 1989.2 The more recent waves have been widely reported in media but still await comprehensive scholarly analysis, especially historical contextualization. Discussing the first two phases with new materials, this chapter places the two recent waves in their unique historical contexts, particularly the increasing ties as well as tensions between China and the United States in the 1990s, and the remarkable rise of China and the shifting power balance between the two nations in the 2000s. The division of the study-abroad movement into four waves therefore offers a fresh, nuanced and historical study of not just post-reform Chinese student migration but also Chinese society and US–China relations, illustrating the constant and dramatic changes even in a short time period of three and a half decades.

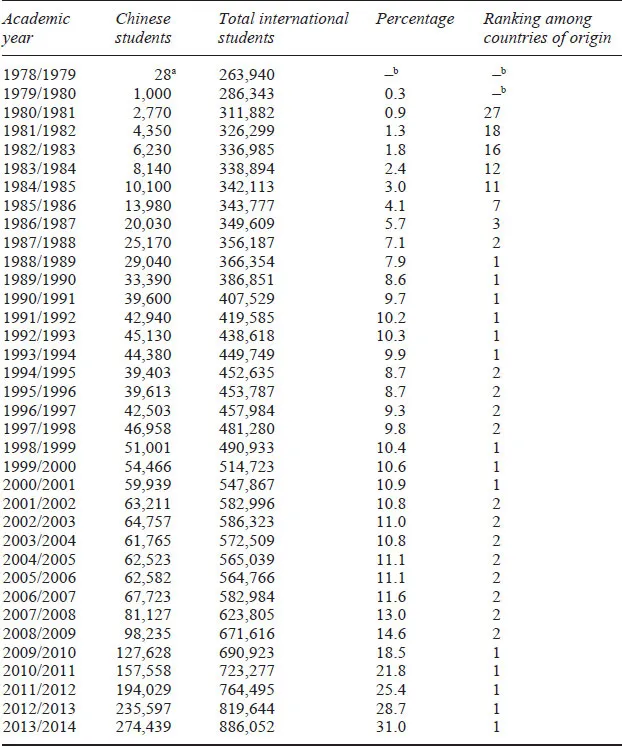

Table 1.1 Mainland Chinese students in the United States, 1978–2014

Notes

Data is compiled based on the annual report (1978–2014) of the Institute of International Education (IIE) entitled Open Doors: Report on International Educational Exchange.

a | This was a “base number” rather than an “extrapolated count” used in the other years. The “base number” is the actual count of students reported by country of citizenship on the survey form sent by the IIE to educational institutions. The “extrapolated count” of total international students includes the sum of the base numbers of each country and the number of international students reported by those institutions that did not specify country of origin. For countries with a base number higher than a certain number (which varied each year, such as 90 for 1978/1979 and 140 for 1980/1981), their base numbers will be modified to determine their extrapolated share of the total student count. Mainland Chinese students started coming to the United States in 1978/1979 after US–China relations were normalized in 1979 and the number of students in this first year was too small to be extrapolated. |

b | The percentage of Chinese students among total international students in 1978/1979 was too low (0.01) to be listed. The rankings of China among all countries sending students to the United States during the academic years of 1978/1979 and 1979/1980 were too low to be indicated in the IIE reports. |

Figure 1.1 Mainland Chinese students in the United States, 1978–2014.

Moreover, this chapter examines and highlights the changing image of the United States among Chinese students and the reinvention of the “American dream” in Chinese society after 1978. Studies of the Chinese image of the United States (and mutual images) have been rich. Some scholars point out the duality of that image: Chinese often viewed the United States with both love and suspicion. As Tu Weiming states, there have been two dimensions of the Chinese perception of the United States, including both admiration (America as the model of modernization) and ambivalence (America as part of the imperialist powers discriminating against China and Chinese), compounded by the persisting cultural divide.3 In their edited volume of Chinese impressions of the United States, R. David Arkush and Leo O. Lee vividly illustrate this historical pattern of mixed and contradictory images of America among Chinese, seen from the titles they use for the different sections of the book such as “Menacing America” and “Model America.”4 China-based scholars also point out this pattern of duality. Zhang Jishun argues that nationalism and modernization have constituted each other, which has been a major contradictory theme in Chinese intellectuals’ self-consciousness and identity. This was reflected in the dual image of the United States historically as both admirable (the America in America) and resentful (the America in China).5

Scholars have also analyzed the mutual imagery in the context of shifting US–China relations. Political scientist David Shambaugh argues that the “love–hate syndrome” generally parallels and underlies the repetitive cycle of US–China relations from mutual enchantment to raised expectations, to unfulfilled expectations, to disillusionment and disenchantment, to recrimination and fallout, to separation and hostility, and then to re-embracing and re-enchantment.6 Adopting the perceptual-psychological approach in the studies of international relations, Jianwei Wang further unravels the various dimensions (cognitive, affective and evaluative orientations) of the mutual images, and he suggests that it is not simply a pattern of recycling but an upward linear model that entails increasing sophistication and maturity: each nation comes to see the other as a multifaceted society (i.e., there are many different “Americas” and “Chinas”).7

In fact, all the above discussions reveal that Chinese perceptions of the United States have been based on the condition and identity of Chinese society itself. As Tu articulates,

the Chinese have been struggling to develop a new identity and to survive as a sovereign nation. Such a struggle … must be seen as a trauma at all levels of Chinese life. In this sense the United States played distinctive roles in initiating and defining that trauma, sometimes as a model of changes and sometimes as a military and cultural threat.8

As Yang Yushen mentions in his historical study of Chinese understanding of the United States, “in the end, Chinese intellectuals perceived the United States mainly based on the needs of finding the ways for their homeland to develop and progress.”9 The basis on one’s own needs in the construction of the image of others is most vividly explicated in sociologist Richard Madsen’s study entitled China and the American Dream, which was published in the wake of the Tiananmen Square Incident. While Madsen uses this analytical framework mainly to unravel the American imagination of China (the “American dream” held by Americans concerning how China could and should follow the model of American society) from the rapprochement in the 1970s to the Tiananmen Square Incident in 1989, the framework can also be applied to the construction of the “American dream” among Chinese based on their political, economic and social needs, and on the realities of Chinese society.10

This chapter adopts Madsen’s analytical framework to analyze the “American dream” in China as a myth constructed based on China’s own identity and reality. Focusing on Chinese students’ imaginations and understandings of the United States in recent decades, it makes three arguments. First, the fever of Chinese studying (and staying) in the United States has not faded but instead has heightened in the decades after China started its reform in 1978, as seen in the four continuing waves of student migration and particularly the recent surge of younger students along with professionals leaving China for the United States. Second, the myth of the “American dream” has been constructed based on the particular social, political and economic contexts of each of the four waves of student migration. Some observers summarize the early waves of students and scholars going abroad as “tao-huang” (escaping poverty) and “tao-nan” (escaping persecution), i.e., leaving China for basic economic and political wellbeing.11 The more recent wave of students and professionals going abroad shows a new pattern of a lesser emphasis on life opportunity (economic and social opportunities that are now accessible in China) and a greater emphasis on life quality (such as food safety, air quality and public morality), which constitutes the new “American dream” in contemporary Chinese society. Third, the current surge of student and professional migration reveals the dilemma of the “Chinese dream”: an increasingly wealthy and powerful China ironically can’t retain its own citizens or convince migrants to reclaim it as their home. The rise of China, bolstered by its remarkable economic growth but overshadowed by its inadequate political reform and deteriorating environmental conditions, has not negated the deeply rooted “American dream.”

The first wave: from 1978 to the mid-1980s

The first wave of post-reform Chinese student migration was from 1978 to the mid-1980s. With the normalization of US–China relations in 1979, China sent 19,000 students and scholars to the United States between 1978 and 1983, about half of all Chinese students and scholars sent abroad at that time.12 The majority of them studied science and technology, revealing the traditional emphasis of the Chinese state on these subjects as the key to modernization. More than half of Chinese students and scholars came from three urban areas (Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong), revealing the concentration of China’s “human investment” in a few metropolitan and coastal centers. More than 60 percent came with J-1 exchange scholar visas, and around half of them were more than 40 years old, though the age of exchange scholars became younger later. Women comprised only 23 percent of these students and scholars, and the ratio was even lower (19 percent) among J-1 exchange scholars, reflecting the common pattern of male-dominance in the academic fields of science and technology. Mainly sent by the state and leaving families in China, most Chinese students and scholars at this time returned after their training in the United States.13

The quick development of the first wave of Chinese students studying in the United States could be attributed to the global geopolitical context in the 1970s, and illustrated the active and earnest participation of both nations in educational exchanges after three decades of separation and hostility. The rapprochement between the United States and China, epitomized by Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972, was based on the geopolitical needs of both countries: The United States was in desperate need of getting out of the Vietnam War and thwarting the increasingly aggressive Soviet Union, while China sought to avoid the dreadful fate of being threatened by two superpowers at the same time.14 American perceptions of China had also changed since the 1970s. While earlier China was viewed primarily as a Marxist-Leninist state with fundamental ideological conflict with the West, now it was received as a society committed to reform and in need of assistance.15 Aligned with American national interests and public opinion was the active participation on the part of American educational institutions, and the rapid reestablishment of US–China educational exchanges revealed the deep historical root of American educational engagement with China that reached far back to the nineteenth century.16 As for China, the fast growth of its study-abroad program was based on the historical tradition since the mid-nineteenth century of learning from the West and Japan to modernize the nation. As David Lampton and his associates succinctly summarized in 1986, the educational exchange between the United States and China after 1978 was not a new invention but a renewal of historical ties between the two countries, and it displayed similar patterns, such as the Chinese government’s active role in the study-abroad program and China’s emphasis on science and technology as the key to its modernization.17

There were also significant challenges at this time. In a congressional research report in 1976 on US–China scientific exchanges since the rapprochement in the early 1970s, Leo Orleans was quite pessimistic, claiming that the interactions were mainly symbolic (for political reasons) rather than substantial, that China was mainly concerned with its national pride and insecurity and therefore restricted foreigners’ access to the dark side of Chinese society, and that the exchanges might just benefit China but not the United States, considering Ameri...