eBook - ePub

Freshwater Recreational Fishing

The National Benefits of Water Pollution Control

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Freshwater Recreational Fishing

The National Benefits of Water Pollution Control

About this book

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act, signed into law in 1972, dramatically redirected the nation's water pollution control efforts and set out ambitious national goals, expressed both in terms of discharge controls and of resulting water quality. Originally published in 1982, this title examines the benefits that a reduction in the discharge of water pollutants has for recreational fisherman including an increase in the total availability of fishable natural water bodies and an improvement in the aesthetic quality of the fishing experience. It is a valuable resource for students interested in environmental studies and public policy making.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Freshwater Recreational Fishing by William J. Vaughan,Clifford S. Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Problem and the Approach

Background

One of the most important pieces of national environmental legislation created during the 1970s was the comprehensive amendment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA(A)). These amendments, signed into law in 1972, in reality constituted a major piece of legislation in their own right, dramatically redirecting the nation's water pollution control efforts and setting out ambitious national goals, expressed both in terms of discharge controls and of resulting water quality. The earlier version of FWPCA (encoded in PL 87-88 of 1961) and the Water Quality Act of 1964 (PL 89-234) set up a system of ambient water quality standards chosen by the states with federal guidance. In contrast to this legislation, the 1972 amendments stressed discharge control (Davies and Davies, 1975). The key elements in this new attack on pollution were a series of general control technology definitions with deadlines for their application.1

Effluent limitations based on best practicable control technology currently available (BPCTCA or BPT for short) were to be applied to all private point sources of waterborne waste discharge by July 1, 1977.

Effluent limitations based on best available technology economically achievable (BATEA or BAT for short) were to be applied to all private point sources of waterborne waste discharge by July 1, 1983.

Effluent limitations based on "secondary treatment" as defined by the administrator (of EPA) were to be applied to publicly owned treatment plants by July 1, 1977. Further, by July 1983, application of "the best practicable waste treatment technology over the life of the works" was to be required.

The ultimate goal of the national policy was to be the elimination of all pollution discharges to navigable waters by 1985. (This, for obvious reasons, became known as the zero-discharge goal.)

This concentration on requiring discharge controls based on "practicable," "available," and "economically achievable" technologies was meant to avoid problems of translating ambient water quality standards into legally enforceable requirements on particular polluters. But the makers of the 1972 amendments did not entirely abandon direct concern for the ambient environment. In particular, they allowed for interaction between existing state ambient water quality standards and the technology-based treatment standards by requiring more severe discharge reductions than those of BPT if the BPT-based reductions failed to achieve the existing ambient water quality standards (Section 301(b)(1)(C)). In addition, the Congress inserted its own ambient water quality standard in the so-called "fishable-swimmable" goal of Section 101(a)(2): "...it is the national goal that whenever attainable, an interim goal of water quality which provides for the protection and propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water be achieved by July 1, 1983." If it will not be met by the application of BAT-based effluent standards, the administrator is to establish stricter effluent limitations that would give the desired result (Section 302).2

This piece of legislation covers a great deal more than the definitions and requirements mentioned above. For example, it establishes a mechanism for encouraging regional planning and coordination of pollution control efforts; contains provisions about dredge and fill operations and the protection of wetlands; and defines the design and construction subsidy system for municipal sewage treatment plants—the massive incentive to encourage compliance by unhappy local governments faced with very large costs. However, technology-based treatment requirements and the very aims for ambient water quality, not to mention the zero-discharge goal, have dominated most discussions of the amendments.

Criticisms of the amendments and debate over their goals and requirements began during the legislative process and has continued to the present. The critical positions are that the goals are too ambitious and that the treatment requirements designed to reach the goals are severely flawed, being both highly inefficient in the short run and inimical to technological improvements over the long run. By "too ambitious" the critics mean, and often explicitly say, that the benefits to be expected from meeting the goals (and related requirements) are not large enough to justify the cost of compliance.3 This line of criticism may be said to have been vindicated, at least to some limited extent, by further amendment of national water pollution control policy in 1977. This legislation relaxed some of the treatment definitions and compliance dates of the 1972 amendments.4 (It also changed the name of the much-amended law to the Clean Water Act.)

Nevertheless, the debate continues, the relaxations being insufficient to persuade all interested parties that the benefits now clearly outweigh the costs. It is this continuing uncertainty about and disagreement over benefits that may be said to have given rise to the work reported in the following pages, for it is our intention to help inform the debate between critics and defenders of the amendments. In particular, we aim to present both an improved estimate of one part of the full set of benefits attributable to implementation of the legislation, and a method potentially applicable to other parts of the set. In the process we must ignore the other major line of critical argument—the failings of the technology-based standards approach.5

The beginning of the decade of the 1980s seems an especially propitious time for this effort because the rhetoric, at least, of the public debate over government action currently stresses the importance of measuring and comparing the benefits and costs of all forms of intervention.6 In the past, it has appeared that benefit-cost analysis was more a matter of assertion than of analysis. Those who favored the amendments (and other environmental legislation for that matter) often referred to the benefits as "incalculable." Their opponents denied the existence of some categories of benefits and suggested that total benefits, far from being incalculable, were obviously too small to justify the costs implied by the new policies. Neither side had any persuasive and comprehensive estimates to back up their assertions.

Some Preliminary Evidence: Aggregates and Categories

We do not wish to exaggerate the current poverty of knowledge of the costs and benefits of water pollution control. There are routine, ongoing efforts to measure costs. While more sporadic, efforts to obtain values for benefits have certainly not been completely lacking. In order to provide some perspective on the importance of this legislation to the economy, a very rough idea of the relative magnitudes of benefits and costs, and guidance about the significance of particular benefit categories, it is worth considering some of the existing evidence. First, however, a few cautionary notes are in order.

While this book is concerned with benefit, not cost, estimation, measuring the costs of the nation's water pollution control program is a far from trivial problem. There are difficulties of definition. For example, there is the question of what costs really are to be attributed to the program and which would have been voluntarily incurred in any case, perhaps to recover a valuable by-product for recycling. On the other side, actual out-of-pocket costs, reflecting public subsidies, must not be confused with real program costs. Beyond definition lies measurement, and here the basic choice is between asking dischargers to report or project their own control costs, and developing "synthetic" costs for hypothetical implementation of the program using engineering-economic estimation of what this would require. Each method has its problems and strengths, but a difficulty facing both is the necessity of having some quite specific idea of how the program, in this case the rather general language of the technology-based standards, will actually be translated into required actions for dischargers.7

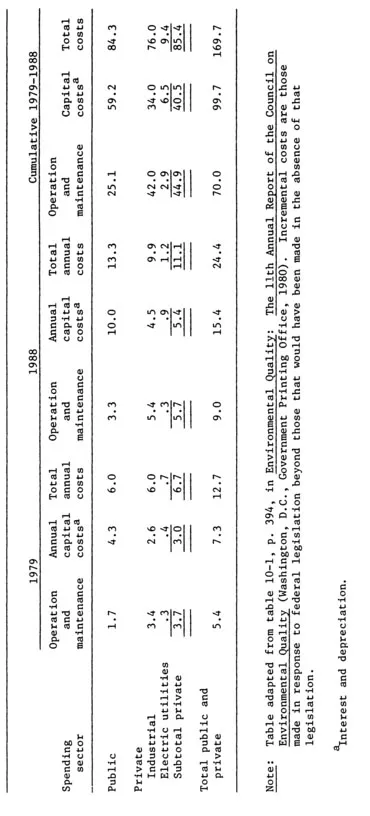

Bearing in mind that cost estimation and projection is not a simple pro forma exercise, we may examine table 1-1 with a view to understanding both the size of the national commitment represented by FWPCA(A)/CWA, and the distribution of that cost over time and major economic sectors. According to the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), total incremental expenditure on water pollution abatement was $12.7 billion in 1979 (1979 dollars). This is roughly the same amount of spending as that devoted to replacement auto parts and about 90 percent of the sales of the health care and hospital supply industry in 1979.8 It was about equally divided between public (we may assume primarily municipal) polluters and industrial sources. Electric utilities are estimated to have spent 5.5 percent of the total.

CEQ estimates that by 1988 incremental expenditures on water pollution abatement will have about doubled (in 1979 dollars) to $24.1 billion per year. This represents an average annual rate of growth in real terms of almost 7 percent, considerably higher than even the most optimistic projections of the GNP growth rate. Therefore, this spending will necessarily increase in relative importance, however measured.9

Table 1-1. Estimated Incremental Water Pollution Abatement Expenditures 1979-88

(billions of 1979 dollars)

(billions of 1979 dollars)

If defining and measuring costs is hard, the production of believable benefit estimates for water pollution control is much harder. A first problem is that for the most part these benefits do not involve marketed goods. (Commercial fishing is an exception, but a fairly lonely one.) This is not a matter of happenstance, of course, but a reflection of the fact that for a combination of technical and traditional or customary reasons, the major relevant service outputs of natural waterways (for example, recreation, contribution to scenic vistas) involve public goods—goods available to all, once provided to any. In addition, for another potentially important category of use—drinking water—some major damages of pollution, and hence the benefits of its control, are tangled in the technical difficulties and economic enigmas surrounding human health effects (morbidity and mortality). To make matters even worse, there are persuasive a priori arguments that some important categories of benefits do not involve human use at all, even in the indirect sense of viewing scenery. For example, it has been asserted (and to some limited extent supported by evidence; see Mitchell and Carson, 1981) that people are willing to pay significant amounts just for the knowledge that a pollution control program is resulting in a comprehensive improvement in national water quality. This is quite independent of use, or indeed of intent to use, those waters.10

Undaunted if not unhindered by this array of problems, researchers, especially over the past decade, have produced a number of estimates of national water pollution control benefits within several categories. These individual pieces have been brought together, with critical comment and professional judgment, by Freeman (1979a); the results of his efforts are summarized in table 1-2.

A first observation based on tables 1-1 and 1-2 is that on this evidence the benefit-cost balance for water pollution control is a very near thing. Thus, Freeman's "most likely point estimate" for aggregate benefits ($13.9 billion per year in 1979 dollars) is only 9.4 percent higher than CEQ's cost estimate for that year. Even this tentative conclusion must further be tempered with caution. Not only do the ranges reported by Freeman suggest very great uncertainty; his interpretive remarks and examination of individual studies raise another issue: that the "pollution control" assumed for the benefit estimates may not be consistent across benefit categories and is certai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Problem and the Approach

- 2. Measuring and Predicting Water Quality in Recreation-Related Terms

- 3. The Probability of Participation in Recreational Fishing

- 4. Participation Choices and Angling Intensity

- 5. Valuing a Fishing Day

- 6. Results and Conclusions

- Appendix A: Valuation in the Context of the Household Production Function Model

- Appendix B: Designing "Almost-Proportional" Samples for Logit Estimation

- Appendix C: Using Case Weights in SAS Regressions

- Appendix D: Methods for Detecting and Correcting for Heteroskedasticity