![]()

1

Introduction

Bruno Taut’s Glashaus was an extremely influential example of early modern architecture. As such, it is widely discussed in architectural history and extensively referenced (Ching, Jarzombek and Prakash, 2007; Colquhoun, 2002; Curtis, 1996; Frampton, 2007; James Chakraborty, 2000; Richards and Gilbert, 2006; Sharp, 1966; Sharp, Scheerbart and Taut, 1972; Thiekotter, 1993; Watkin, 2005; Whyte, 1982). Constructed for the Werkbund Exhibition in 1914, the Glashaus is generally classified as Expressionist in its style. Although the purpose of the building was to showcase the products of the glass industries, the deeper ‘theoretical’ intentions of the building encompassed a complex mix of cosmic mysticism and utopian ideals.

But given the passage of time, why should anybody care about Bruno Taut’s Glashaus? After all, it was only a small exhibition building at a relatively obscure exhibition, which existed as a physical object for a few short weeks during the summer of 1914. To answer this question, one needs to view the Glashaus as a powerful and seductive metaphor. With the story of the Glashaus, architectural history has been written, contested and reinvented numerous times. Even at its 100th year anniversary, the Glashaus still taunts and disturbs architectural history.

The parameters of debate concerning Taut and the Glashaus have been largely established through the writings of Reyner Banham (1959), Dennis Sharp (1966; 1972) and Iain Boyd-Whyte (1982; 1985). In his 1959 article, ‘The Glass Paradise’, Banham was the first English-language author to expose the unique relationship between Taut and the bohemian poet Paul Scheerbart. Banham (1959) contended that there was a hitherto-overlooked prophetic ancestry of odd personalities, myths, and symbols. He argued that events in Germany immediately before and after World War One demanded further study. To this end, Banham first proposed two key, but previously over-looked, personalities who emerged from this period that needed to be added to the list of key modernist figures: Paul Scheerbart and Bruno Taut. By linking Scheerbart and Taut to the Glashaus, Banham presented an argument that countered the accepted history of the modern movement by introducing a light-mysticism as well as the cultures and practices of the Orient and Gothic Europe, which he believed ultimately, influenced the design of the Glashaus. Banham suggested that it would be appropriate to enquire as to the Glashaus’ origins as the building was both vastly dissimilar from and yet exceeded any of Taut’s previous designs (Banham, 1959: 87). In doing so, Banham (1959) concluded that the history of the modern movement required rewriting because of its narrow linear perspective and thus its exclusion of an important literary influence like Scheerbart.

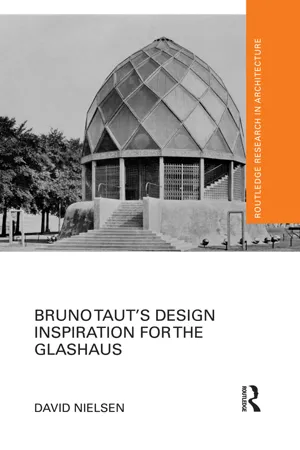

Figure 1.1 Bruno Taut’s Glashaus at the Werkbund Exhibition of 1914 in Cologne. Photo by permission of Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

Although ‘The Glass Paradise’ first appeared in 1959, it is a valuable resource for any study on the Glashaus. Numerous authors have subsequently accepted Banham’s argument, and, through their research, uncovered key facts concerning the Glashaus.

In 1966, Dennis Sharp accepted Banham’s interdisciplinary challenge by documenting the Expressionist origins of modernist architecture in his publication, Modern Architecture and Expressionism. Rosemarie Haag Bletter (1973) published her dissertation, Bruno Taut and Paul Scheerbart’s Vision: Utopian Aspects of German Expressionist Architecture, in which she systematically explored the Taut–Scheerbart relationship. Haag Bletter (1981) further developed her initial argument in, ‘The Interpretation of the Glass Dream: Expressionist Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor’, in which she traced the mystic and historical associations of crystal and glass. In the early 1980s, Iain Boyd Whyte also responded to Banham’s call with two publications: Bruno Taut and the Architecture of Activism (1982) and Crystal Chain Letters: Architectural Fantasies by Bruno Taut and His Circle (1985). As a result of these publications, which formed part of the debate to revise the accepted history of modernism, Scheerbart and Expressionism are now included in most contemporary histories concerning Bruno Taut and the Glashaus (Colquhoun, 2002; Curtis, 1996; Hix, 2005; Thiekotter, 1993).

It was the generally accepted view that the Glashaus constituted an Expressionist exhibition pavilion, which resulted from the mutual efforts of Paul Scheerbart and Bruno Taut. In the 1990s, there was a resurgent interest in Bruno Taut. During this period, numerous additional German publications became available on Taut. These included Angelika Thiekotter’s 1993 publication Kristallisationen, Splitterungen: Bruno Taut’s Glashaus (Crystallisation, Splintering: Bruno Taut’s Glasshouse), and Leo Ikelaar’s 1996 publication Paul Scheerbart’s Briefe von 1913–1914 an Gottfried Heinersdorff, Bruno Taut und Herwarth Walden (Paul Scheerbart’s 1913–14 Letters to Gottfried Heinersdorff, Bruno Taut and Herwarth Walden). In 2005, Kai Gutschow published his dissertation, The Culture of Criticism: Adolf Behne and the Development of Modern Architecture in Germany, 1910–1914, in which he re-established the importance of art critic Adolf Behne’s contribution to the Glashaus. Manfred Speidel (1995) also called into question Scheerbart’s contribution to the Glashaus’ design, revealing that Scheerbart only met Taut a few months before its construction – after Taut had finished his preliminary sketches. Kurt Junghanns (1983) had earlier asserted that the Glashaus design was complete before Taut and Scheerbart ever met.

Gutschow (2005) proposed that the Glashaus was a collaborative result of Taut, Scheerbart and Behne. He argued each of them played a distinct role: Taut was responsible for the overall design of the Glashaus, including the circulatory experience, the geometry, the reinforced concrete structure of the dome, the water cascade, and the stained-glass artwork; Scheerbart’s role was that of a theorist; and Behne was the official historian of the Glashaus. However, Behne’s inclusion into the official history of the Glashaus was not without significant implications. Gutschow (2005) argued that his inclusion was problematic because he over-emphasised the Expressionist link to the Glashaus. Behne was actively seeking to link Expressionism to architecture, a link that did not exist before the Glashaus. It was through Behne’s involvement with the Glashaus that the enduring link with Expressionism was first forged. It was through Behne’s prolific writings, and not through Taut, that the Glashaus was initially labelled as Expressionist. According to Gutschow (2005), this labelling was particularly troubling considering that nobody contributed more to the original literary record concerning the Glashaus, Bruno Taut, and Expressionism than Behne. As such, Behne’s original writings could be argued as having unduly influenced the secondary sources of Banham (1959), Sharp (1966) and Boyd Whyte (1982; 1985).

Although it is not possible to ‘experience’ the Glashaus anymore, a close interpretation is still feasible due to the existing black-and-white photographs and the technical documentation that was submitted to the Cologne City administration. This is despite the fact that Gutschow concluded his reassessment by stating:

Unlike permanent buildings that are more readily reinterpreted by later generations of viewers, Behne’s reviews, his panegyrics on Scheerbart, and the few remaining photographs, became the lens through which all subsequent interpretations have been made.

(Gutschow, 2005: 270–1)

Following Banham’s initial provocation, all of the authors mentioned above have sought to explain the Glashaus’ origins in a wider cultural context. Yet, if one takes into account the gradual marginalisation of Taut’s own motivations and the influences upon him as the architect of the project, as well as the questions raised over the level of Scheerbart’s and Behne’s input, the outcome reveals that an architectural historical analysis remains as important and pressing as ever. It is still appropriate to question the current understanding of the Glashaus. Has the historical record not been misled into believing that the Glashaus is Expressionist? Furthermore, on the basis of the subsequent research, it is fair to question whether Scheerbart’s role has been overstated. While Taut was responsible for the overall design of the Glashaus, it was Expressionism that provided much of the theoretical basis for the design details of the building. Indicative of this tendency, Regine Prange (1991) credited Scheerbart as having been responsible for the ‘details’ of the glazed floor of the Dome Room, the kaleidoscope, electric lighting and glazed internal partition walls of the Glashaus. Speidel (1995) credited Scheerbart as having been responsible for the ‘details’ of lamp fittings and double-glazing. The Expressionist focus has effectively ignored Taut’s central motives, while concentrating on the contributions of Scheerbart and others in the design of the Glashaus. This book proposes that an alternative explanation for the origins of the Glashaus needs to be formulated that returns to re-examine the sources that influenced the central contribution of Taut.

This task is not as easy as it might sound as Taut left nothing that identified his design motives for the Glashaus. He did however leave certain key writings, that when combined with insight into his life, reveals tantalising clues as to his formulation of the Glashaus. Key amongst these writing are a pamphlet that he prepared for the opining of the Glashaus, ‘Glashaus: Werkbund-Ausstellung Köln 1914, Führer zur Eröffnung des Glashauses’ (‘Glashaus: Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne 1914, A Guide to the opening of the Glasshouse’) and little known film script ‘Die Galoschen des Glucks’ (‘The Lucky Shoes’).

This book addresses these limitations in understanding by revealing some crucial motives and inspirations behind the design of the Glashaus.

Figure 1.2 The interior staircase of the Glashaus that led upward to the Dome Room. Photo by permission of Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

These have not yet been fully accounted for in any previous study. This book will therefore contribute to the re-evaluation of the generally accepted histories of the Glashaus and, in the process, the modern movement. Yet, this work is not a comprehensive account of the careers of Scheerbart, Behne, or Taut – or even the term Expressionism; numerous authors have already undertaken these studies. Equally, this thesis does not totally dismiss the roles played by Behne and Scheerbart in the Glashaus. Instead, this work accepts that they played a role, albeit a more limited one than outlined in various prior studies. What this book establishes...