![]()

Chapter One

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT STRESS – A MODEL BASED ON RESEARCH

INTRODUCTION

Everybody experiences stress in their lives, from the rural Scottish crofter, to the suburban mother, to the high-flyer business executive. Throughout history people have experienced stress – it is part and parcel of the human condition as chronicled in art and literature throughout the ages.

The pervasiveness of stress in our society is evident in the variety of ways our language is able to express it; you might say, ‘I feel wound up/under strain/under pressure/tense/panicky/uptight/agitated’. Whatever phrase we may use, stress happens to us all.

The stress of everyday life shows itself in lots of ways: an angry snapped reply to an innocent question, a pounding headache at the end of a hard day at work, the driver drumming their fingers on the steering wheel in a traffic jam. These daily stresses are normal. However, with prolonged and more serious stress people often begin to develop troublesome symptoms which they worry about. It is at this point that they might look for outside help, and often the first port of call is the local general practitioner. In most cases the doctor will offer help, reassurance, and possibly even medication. In some cases where the individual is coping inadequately, they will be referred on to a mental health worker or a community mental health team – usually consisting of such professionals as clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists, counsellors, and community psychiatric nurses. This book is written as a clinical resource and practical guide for those professionals, but will also be useful as a handbook for the clients themselves and any member of the public with an interest in self-help methods of managing stress.

THE SIZE OF THE PROBLEM

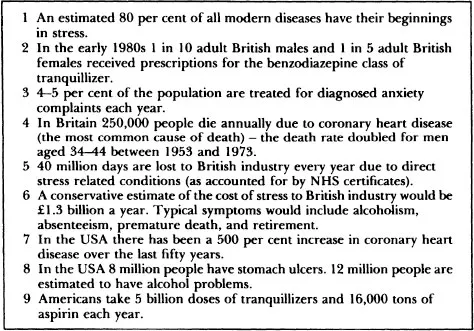

Although people have experienced stress throughout history, there is evidence to suggest that the problems associated with stress have escalated during the twentieth century, particularly in highly developed westernized countries. Let us pause to consider a few statistics which will put the problem of stress in context (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The size of the problem: a few statistics

What is the explanation for the increase in these stress related conditions? A commonly held view is that the ‘pace of life’ has increased. Sociologists might identify factors such as the decline of traditional structures such as community networks and extended families, the decline of commonly held values, beliefs, and rituals incorporated in traditional religions, changing working practices, greater social and geographical mobility, poor diet, lack of exercise, the restrictive medicalization of symptoms, or even the fact that we are now more vigilant record keepers. All these factors have been linked with trying to explain the increase in reported stress related problems. It seems likely that there is some truth in all these arguments. However, although it is important to be aware of these issues, sociological discussion about the causes of stress are beyond the scope of the book.

A WORKING MODEL OF STRESS

Before contemplating any form of therapeutic intervention it is important to have an understanding or a model of stress. This model is very much like a map of the general landscape giving us direction and helping us to see our way forward. All of us carry around in our heads some form of idiosyncratic model of stress; some people’s models or ideas may be more sophisticated, complex, or explicit than others. For the purpose of this book it is important to articulate that model at an early stage as it is the basis for understanding all that follows.

Before examining our model let us first attempt to define the subject of that model, namely the term stress. Lazarus gives us the following formal definition of stress: ‘stress refers to a broad class of problems differentiated from other problem areas because it deals with any demands which tax the system, whatever it is, a physiological system, a social system or a psychological system and the response of that system’ (Lazarus 1971: 53–60). He goes on to say that the ‘reaction depends on how the person interprets or appraises (consciously or unconsciously) the significance of a harmful, threatening or challenging event’ (ibid.).

This definition contains three important components for a model of stress:

1 The idea of demands taxing a system.

2 The idea that there is some form of appraisal or perception of threat.

3 The importance of the response of that system.

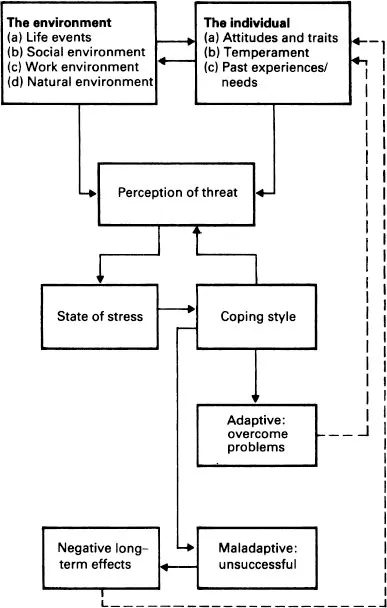

The notion of demands taxing an individual or a system implies a temporary state of unbalance or disequilibrium. These demands are not just a result of external forces acting on a point, as in the case in the engineering definition of stress, rather they are the result of the interaction between external forces and the internal factors which make up an individual or system. Both these external environmental factors and internal individual factors can be further broken down into a number of separate categories. Empirical research has demonstrated that each of these categories have a significant part to play in the process of stress (see Figure 1.2). A circular or transactional relationship exists between the individual and their environment – both influence and effect each other. Out of this transactional relationship develop different states of equilibrium and disequilibrium or imbalance. This process does not go on unnoticed as some form of conscious, or unconscious, judgement is being made continuously. This judgement or perception of threat is largely determined by factors which make up an individual, such as one’s thoughts, attitudes, past experiences, temperament, physical make-up, and factors in the environment. This perception of threat will influence the resultant state of stress, which will manifest itself in different areas of physical, cognitive, and behavioural symptoms. The individual or system will react to this state of stress in an attempt to restore equilibrium. This reaction is important as it directly affects the future abilities and character of the individual. Some reactions can be viewed as adaptive as they move the system on to a further state of equilibrium, reducing overall demands. Other reactions could be viewed as maladaptive as they create further secondary problems which adversely affect the future of the individual.

The model of stress is very similar to the notion of homeostasis in the natural world as elaborated by Cannon (1929). Stated simply: a system or individual when unbalanced will strive to re-establish equilibrium. Sometimes that system or individual may need help and this is the underlying basis of anxiety and stress management counselling. The model offers a comprehensive framework for incorporating and understanding all stress related problems. The rest of this chapter will examine and explain further the different individual components of the model.

THE ENVIRONMENT

Life Events

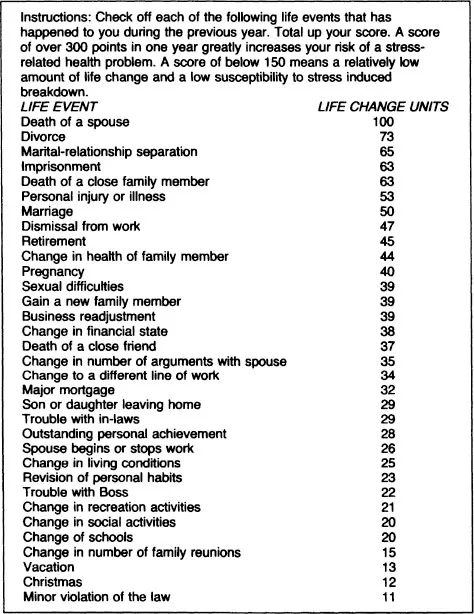

A considerable body of work, originating from the research of Holmes and Rahe (1967), suggests that certain life events that cause change, increase an individual’s susceptibility to stress-related illness. In a number of studies, they weighted particular life events on a scale from 0 to 100 and looked at a selected heterogeneous population sample, both prospectively and retrospectively (see Figure 1.3). These life events involved change of some kind, including changes in health, family relationships, economic and living conditions, education, religion, and social affairs. They ranged in severity from major life crises, such as death of a spouse, to relatively minor events, like going on holiday or receiving a parking ticket. Each individual was given a total life change score for a given period of time. They found that individuals with high life change scores were more likely to have a stress related illness during the following two year period.

Figure 1.2 A working model of stress

Source: Adapted from Cooper (1981)

Figure 1.3 The Holmes–Rahe Life Stress Inventory

Correlational studies suggest a relationship between life change scores and the onset of tuberculosis, heart disease, skin diseases, a general deterioration in health, and poorer academic performance. Further studies found a relationship with psychiatric symptomatology; a net increase in life events was associated with worsening of symptoms and a net decrease with improvement. These researchers contend that it is the nature of change itself which is stressful, regardless of whether it is perceived as favourable or unfavourable.

In another study looking at changing lifestyle Syme (1966) concluded that men and women whose life situation is significantly different from that in which they grew up have an increased risk of heart attacks. For a farm boy who moves to a large city and takes a ‘white collar’ job there is an increased risk of 300 per cent. If he takes a ‘blue collar’ job the risk is considerably less.

Social Environment

Many researchers (Cassel 1976, Ganster and Victor 1988) have argued that people who are part of an extensive social network are less negatively affected by stressful life events and are less likely to experience stress related health problems. It is also widely maintained that naturally existing support systems, such as extended families, work groups, and communities, facilitate better coping, rehabilitation, and recovery. It has been hypothesized that social support serves as a buffer or mediator between life stresses and poor health.

The term social support refers to personal contact available to an individual from other individuals or groups. This contact produces a number of obvious benefits:

1 The individual is provided with a means of expressing his or her feelings.

2 Feedback from others is important in helping to develop an appropriate appraisal of a situation and realistic goals, also helping the person establish a sense of meaning.

3 Social contacts can also provide useful information and practical help.

A number of studies have suggested that people who live alone and who are not involved with other people or organizations are more vulnerable to a variety of stress related chronic illnesses. Lynch (1977) argued that the socially isolated die prematurely. He compared mortality figures indicating that married people experience a lower mortality rate (from all diseases) than unmarried people. Research studies have shown that members of certain religious groups have lower incidence of stress-related health problems, attributed to their tightly knit and cohesive communities. In many cases it is not the quantity of contacts but the quality or relationship. One study, Brown and Harris (1978), showed that women who had one important confiding relationship with a husband, lover, or friend, were 90 per cent less likely to become depressed than women who had no such relationship to rely on.

Work Environment

An aspect of life that has received much attention from researchers is work. Apart from providing financial income, work can satisfy a number of basic human needs – mental and physical exercise, social contact, feelings of self worth, confidence, and competence. However, work can also be a major source of stress. Cooper (1981) outlines a number of stress factors at work (see Figure 1.4).

Working Conditions

There is ample evidence that physical and mental health is adversely affected by unpleasant working conditions, such as excessive noise, too much or too little lighting, high temperatures, and excessive or inconvenient hours.

Work Overload

Quantitative overload refers to having too much to do. You may be competent at your job but time pressure, long hours, unrealistic deadlines, frequent interruptions, and lack of appropriate rest intervals can all elicit a stress reaction.

Qualitative overload means the work is too difficult and the job exceeds the technical and intellectual competence of the individual. The job may involve continuous concentration, high level decision-making and dealing with sophisticated information and the individual may lack the ability to cope with it.

Work Underload

The job fails to provide meaningful psychological stimulation. The individual may feel bored because of the job’s repetitive nature, or frustrated because there is no opportunity for self-expression.

Role Ambiguity

The individual has inadequate information about their work role: there is a lack of clarity about work objectives, respons...