- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Amply illustrated with pen & ink drawings, and including a glossary of key terms, this volume, originally published in 1955, traces the history of firearms and the pioneers who made that history, step by step, to the fringe of a complex modern science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Firearms by W. Y. Carman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

THE USE OF FIRE IN WAR

1. EARLY EXPERIMENTS

THE modern use of the word ‘firearm’ brings to mind a I weapon which expels a projectile by means of a sudden explosion; the ‘fire’ part of the word suggests the result of the exploded gunpowder. But long before gunpowder was invented fire and methods of using it had been employed in warfare.

It is true that the first application would be a direct method, such as when a raider applied a flaming torch to the wooden home of a helpless victim or to the inflammable portions of a fortress. The Assyrians and Ancient Greeks knew well how to use fire for both attack and defence, as may be learnt from bas-reliefs and the tales of Homer. The wielder of fire seeking personal protection used various means of projecting the fire. Throwing a torch was elementary, but vessels or pots with inflammable mixtures, and a burning firehead to an arrow were soon developed. Even these had their defects. A Roman historian of the fourth century urges that such arrows must be shot gently, for a rapidly flying arrow would be extinguished by the displaced air.

It may be recollected that the Bible furnishes an early example of fire being conveyed by animals, on the occasion when Samson ‘went and caught three hundred foxes and took firebrands and turned tail to tail, and put a firebrand in the midst between two tails. And when he had set the brands on fire, he let them go into the standing corn of the Philistines and burnt up the shocks, and also the standing corn, with the vineyards and olives.’ In true Old Testament tradition, the Philistines retaliated also with fire and burnt the wife of Samson and his father-in-law.

An unusual means of producing fire was attributed to Archimedes—that at the siege of Syracuse, he successfully used large burning glasses to destroy the Roman ships. The Pharos at Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was also said to have had a large mirror at the top, which could be used to concentrate the rays of the sun and direct them to burn enemy rigging, even up to the distance of a hundred miles at sea, according to the exaggerated legends. In the Artillery Museum at Stockholm is an ancient burning mirror which may have been intended for something of the same ambitious purpose.

Experiments with such materials as oil, pitch, sulphur and other ingredients were all steps on the road to discover gunpowder, as will be seen later. Even the early crude mixtures added much to the terrors and difficulties of a besieged town. These wildfires were of a sticky nature which not only adhered to any object they hit, but spread and were difficult to put out, especially with water.

At the siege of Plataea in 429 B.C., the Plataeans were forced to put hides and skins over the woodwork of their fortifications to lessen the effect of the flaming missiles of the Pelopponesian attackers. The Spartans on the same occasion used the combustible material in another way. They piled large bundles of wood against the city walls and after saturating them with a mixture of sulphur and pitch, set them on fire. This concoction could have hardly been the far-famed ‘Greek fire’, that could not be extinguished, for a sudden rainstorm put out the flames and saved the walls.

An invention for throwing liquid fire was used by the Boeotians at the siege of Delium in 424 B.C. Thucydides in his fourth book describes a hollowed tree trunk covered with iron. ‘They sawed in two and scooped out a great beam from end to end and fitting it nicely together again like a pipe, hung by chains at one end, a cauldron. Now the beam was plated with iron and an iron tube joined it to the cauldron. This they brought up from a distance upon carts to the part of the wall principally composed of vines and timber and when it was near, inserted large bellows into the end of the beam and blew with them. The blast passing closely confined into the cauldron, which was filled with lighted coals, sulphur and pitch, made a great blaze and set fire to the wall. The defenders could not hold it and fled. In this way the fort was taken.’ Fire from machines was also thrown at the siege of Syracuse 413 B.C. and at the siege of Rhodes 304 B.C.

New mixtures were being made to improve the qualities of the fire, and Æneas the tactician who lived about 350 B.C. has written down his recipe, where he tells us to ‘take some pitch, sulphur, tow, manna, incense, and the parings of those gummy woods of which torches are made; set fire to the mixture and throw it against the object which you wish to reduce to ashes.’ He also advocates egg-shaped containers which when lighted were to be thrown into enemy ships.

2. GREEK FIRE

Little advance seems to have been made in this field until the end of the seventh century A.D. Then appears the famous ‘Greek fire’, so long a terror to the enemies of the ancient Byzantine empire. So effective was it, that its composition became a state secret, with the direst penalties for whoever might reveal it. It is said that it was the invention of Kallenikos, an architect from Heliopolis or Baalbec in Syria. His semi-liquid mixture, known at the time as ‘sea-fire’ was exceedingly difficult to extinguish and water only served to make it more dangerous. This formula Kallenikos brought to the Emperor Constantine Pogonatus for him to use against the Arabs who at that time were besieging Constantinople, the chief city of Byzantium.

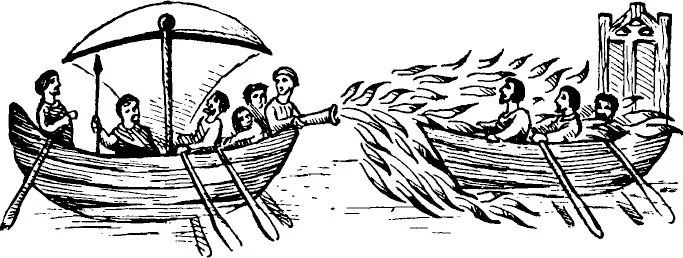

It was used with effect in the following year, A.D. 674 when the Saracenic fleet was destroyed by this new method. The Emperor had projecting tubes fitted to his fast sailing vessels and when the Greek fire was pumped through the tubes on to the woodwork of the enemy’s shipping, it was most difficult to put out; vinegar, wine or sand were suggested as the only means.

Much effort was made to keep this invention a state secret, and it was not written down. The Emperor Constantine the Seventh, Porphyrogenitus, wrote to his son that he should ‘above all things direct your care and attention to the liquid fire, which is thrown by means of a tube; and if the secret is dared to be asked of thee, as it has often been of me, thou must refuse and reject this prayer, stating that this fire had been shown and revealed by an angel to the great and holy Christian Emperor Constantine.’ He made further dire threats to anyone who might reveal the secret to a foreign nation.

Further details of the methods of using this seafire in the late ninth century are given by Emperor Leo the Sixth, also called the Philosopher, who said that the artificial fire was to be discharged by means of siphons. The siphons were made of bronze and, placed in the prow of every war-vessel, were protected by wood. Leo the Sixth, in his Tactics, also tells his officers to use the small hand-tubes which had been lately invented, and when doing so to discharge them from behind iron shields.

It is a daughter of one of these Emperors, Princess Anna Commena who tells us much of these warlike inventions in her book on the life of her father, the Emperor Alexius the First, Commenus. In this work, the Alexiad, she stated that resinous gums from fir and other evergreen trees were to be powdered and mixed with sulphur. When the mixture was blown with powerful and steady breath through hollow canes or tubes and ignited at the tip of the tube, long jets of flame would sear the faces of the enemy like flashes of lightning. But the Princess leaves out important information, thus keeping in part the secret. Various learned men have guessed at the complete solution. Francis Grose in his Military Antiquities says the formula of her day was bitumen, sulphur and naphtha, but Colonel H. W. L. Hime in his Origin of Gunpowder suggests that the missing ingredient is quicklime. He points out that naphtha or anything in the petroleum class was not a normal product of Byzantium and had it been imported, especially from Arab or Saracen countries, its secret use would have soon been guessed. But quicklime could easily be produced in the building craft, without suspicion. And the effect of water upon it would only serve to raise the temperature.

A German writer in 1939, Albert Hauscnstein, said that successful modern experiments had been made with quicklime, sulphur and naphtha, but others in more recent times say that practical experience shows it not to work as the slaking of the quicklime would not be enough to vaporize and ignite the naphtha. The oil in the naphtha would envelope the quicklime particles and prevent them from reacting with water. Direct ignition would, however, be effective. It seems that the secret may never be discovered, which is no great loss as the other developments of modern times leave in the category of playthings what was an epoch-shattering discovery, and prolonged the life of the Byzantine empire for many extra years.

Anna Commena gives useful information about the tubes or siphons when she tells us that ‘in the bow of each vessel the admiral put the heads of lions and other land animals, made of brass and iron, gilt, so as to be frightful to look at; and he arranged that from their mouths, which were open, should issue the fire to be delivered by the soldiers by means of the flexible apparatus.’ The theory of siphons or pumps was well known in Greece and Rome where elementary fire-engines were employed against fires. The siphon on each ship was served by the two foremost rowers, one of whom was called the siphonator and his duty was to ‘lay’ the siphon. The weapon must have been on a swivel because in a sea-battle near the island of Rhodes in 1103, the Pisans were terrified by the apparatus which cast fire at them from all angles, even sideways and downwards. A report of the battle gives us full details. The first encounter of the Byzantine admiral was a fiasco, as he shot his fire too soon and missed the enemy vessel. The next in the fleet rammed a Pisan ship, fired at it and set it on fire. Then the successful attacker disengaged itself and caught three more of the enemy in the deadly blaze; after which the Pisan navy fled from the scene.

The small hand siphons may have been of two types. The first writer tells of a pellet which after being blown from a long hollow tube becomes ignited by a flame at the exit, while the other author describes the charge as projected by air. Bellows, blow-pipes or squirt would all seem to be possible methods of discharging the fire but it is difficult to decide which is meant, and the fanciful pictures of the period showing the fire-ships in action do not help to clarify this point. There is an illustration of a sea battle showing a ship with its blazing tube enveloping the enemy vessel in a mass of flames. This comes from a Greek manuscript of Skylitzes but very little can be learnt, for the fireworker or siphonator leans in the bows with one hand on the tube, while his gaze is directed backwards.

1—Greek fire through syringe.

No other nation seems to have used the Byzantine secret fuel, and thus when the Crusades began in 1097 there were other imitations in the field, mainly based on the old mixture of sulphur, pitch or bitumen, and resin or other gummy substances, with the addition of naphtha or other ingredients. A metrical romance of Richard Cœur-de-Lion written in the reign of Edward the First, tells us that

King Richard oute of hys galye

Caste wylde-fyr into the skye

And fyr Gregeys into the see

And al on fyr were the.

Poetic licence seems to have given the King possession of the secret sea-fire but little evidence supports this.

Incidentally ‘Greek fire’ was not a term in use in either the Greek or Moslem languages and only dates from the time when the Christians came in contact with this liquid fire in the Crusades. No citizen of Byzantium would ever degrade himself or a compatriot by the name of Greek.

But Greek fire was dropping out of use and evidence of its presence after 1200 is lacking. The main reason for its disuse would appear to be that the Byzantines were no longer warlike and had become degenerate. In 1200, the commanding Admiral, Michael Struphnos sold the naval stores in Constantinople and ‘turned into money not only the bolts and anchors of the ships but their sails and rigging and left the navy without a single large vessel.’ The money he appropriated and the secret seems to have disappeared from this time. Four years later when members of the Fourth Crusade attacked their once-allied Christians in Constantinople, the sixteen war-ships had a poor variety of fire which the Venetians soon coped with.

The Saracens were not slow to use fire as a weapon against the Crusaders. At Acre, 1191, the Crusader siege towers were becoming too great a menace, so a Damascus metal worker produced a plan, which went as follows. ‘First in order to deceive the Christians, he cast against one of the towers, pots with naphtha and other materials in an unkindled state, which had no effect whatever. Then the Christians took heart, climbed triumphantly to the highest story of the tower and assailed the faithful with mockeries. Meanwhile the man from Damascus waited until the stuff in the pots was well melted. When the moment had come, he slung anew a pot that was well alight. Straightway the fire laid hold on everything around, and the tower was destroyed. The conflagration was so violent that the infidels had not time to climb down. Men, weapons, everything was burnt up. Both the other towers were destroyed in a like manner.’

Even though this fire may not have been the genuine article as used by the Byzantines, it was sufficient to throw the Christians into great fear. Jean de Joinville, a later eye-witness of its effects, who wrote a Histoire du Roy Saint Loys, speaks of the terrors it effected among the commanders of St. Louis’ army in 1249 at the siege of Darmetta. It was advised that as often as the fire was thrown, all should prostrate themselves on their elbows and knees and beseech the Lord to deliver them from that danger. But the results of this fire do not seem to have warranted this fear, because some of the attacking towers which had been set on fire were soon rescued from the flames. Joinville describes his experience in the following words. ‘The Saracens brought an engine called a petrary and put Greek fire into the sling of the engine. The fashion of the Greek fire was such that it came front-wise as large as a barrel of verjuice [a thirteenth-century flavouring sauce made from the juice of crab-apples] and the tail of fire that issued from it was as large as a large lance. The noise it made in coming was like Heaven’s thunder. It had the seeming of a dragon flying through the air. It gave so great a light, because of the great poison of fire making the light, that one saw as clearly throughout the camp as if it had been day.’ Mention of a large cross-bow being used four times to cast the fire shows that siphons or squirts were not in use, as they had been for the Byzantine fire. Geoffry de Vinesauf in his Itinerari cum Regis Ricardi (he accompanied King Richard I to the Crusades) says of the fire, the ‘oleum incendiarium, quod vulgo Ignem Graecum nominant’ that ‘with a pernicious stench and livid flame, it consumes even flint and iron, nor could it be extinguished by water; but by sprinkling sand on it, the violence of it may be abated, and vinegar poured on it will put it out.’

The type of machine for throwing these barrels of fire could be of the principle of tension (large bows), torsion (twisted rope) or counterpoise (a weight at the end of a swivelled arm). Constant reference to the use of this artillery in European and Asiatic warfare, especially in the flowery language which spoke of thunder and lightning, may have led to the confusion in more modern writers’ minds, that firearms and cannon were in use much earlier than was actually so.

A use of fire in Europe is recorded by Roger de Hoveden, who notes that it was used by Philip Augustus King of France to burn the English shipping in the harbour of Dieppe during a siege in 1193. This monarch had found a quantity of the inflammable material already prepared when he entered Acre and he did not hesitate to bring it to Europe to use against his fellow Christians. Even Edward the First ordered the employment of fire against the Scots at the siege of Stirling Castle in 1304. Fifteen years later a Flemish engineer, Crab, defended Berwick when besieged by Edward the Second, by means of a fiery mixture containing pitch, tar, fat, brimstone and the refuse of flax.

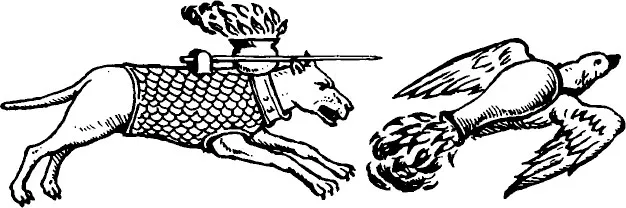

John Ardenne, a surgeon of the time of Edward the Third, proposed that apart from long-bows and cross-bows carrying an incendiary material, birds and animals could carry the fiery composition in iron or brass containers. A manuscript in the Hauslaub Collection in Vienna illustrates a dog in a scaled coat with a spike and a flaming pot on his back pounding forwards to the enemy. A cat and a flying bird are also shown as pressed into this dangerous and uncomfortable service.

2—Fire carried by dog and bird, Middle Ages.

A French manuscript of the fourteenth century shows a large ballista slinging a barrel of flaming material at the enemy while another page of the same manuscript depicts a horseman in armour charging forward with a lance having a blazing head.

On...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- GLOSSARY

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 THE USE OF FIRE IN WAR

- 2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF CANNON

- 3 VARIATIONS OF CANNON

- 4 MACHINE-GUNS

- 5 HANDGUNS, MUSKETS AND RIFLES

- 6 CARBINES

- 7 PISTOLS AND REVOLVERS

- 8 EXPERIMENTS

- 9 AMMUNITION

- 10 GRENADES AND FIRESHIPS

- 11 ROCKETS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX