It is almost inevitable when introducing a book about maritime networks to recall that more than 90 percent of world trade volumes are still supported by maritime transport. Seas and oceans occupy about 70 percent of the Earth’s surface and coastal areas concentrated 16 and 39 percent of the world’s total and urban populations respectively in the 1990s (Noin, 1999). This overwhelming importance is reflected by the great quantity of cultural, social, political, and scientific research about the sea in all its aspects. Dedicated sub-disciplines such as maritime history, geography, engineering, biology, and economics as well as institutions organize large-scale meetings to discuss the organization and evolution of the sea as an ecosystem, a natural resource, and a vector of exchanges.

But what remains striking is that maritime transport has been much less studied than any other transport mode, especially from a network perspective. Existing research remains rather fragmented and scattered across the academic spectrum, which makes it difficult to review it exhaustively and to define any possible common framework. Five main reasons contribute to explaining such a fact: the dominance of a continental culture favouring studies of populated rather than “empty” spaces (Steinberg, 1999; Lewis and Wigen, 1999); the vague geographic distribution and morphology of maritime flows due to the absence of a track infrastructure (White and Senior, 1983; Rodrigue et al., 2013); the capture of most passenger and information flows by air transport and telecommunications since the second half of the twentieth century; the continuous decline of maritime transport costs compared with other logistics costs; and the reluctance of scholars and experts to access and compile costly and hard to obtain maritime traffic statistics.

The World Seastems project No. 313847, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) over the period 2013–18, is aimed primarily at compiling and analysing untapped historical records of global vessel movements over the contemporary period. Its international workshop held in June 2014 at the Paris Institute for Complex Systems (ISC-PIF), gathered many researchers with a similar focus, namely to provide a quantitative analysis of maritime networks in space and time. In so doing, the 20 chapters of the present book, written by 40 scholars from 12 countries and 10 academic backgrounds, offer a multidisciplinary perspective about one of the most vital pillars of world society.

The maritime network: late emergence of a multifaceted concept

A simple online search via Science Direct provided about 100 results for “maritime network” (as of 16 September 2014) compared with more than 10,000 results for road, global, or transport network, taking into account all scientific disciplines. Airline network scored 261, while trade, logistics, street, river, and railway ranged between 1,000 and 4,000 results each. Among maritime-related terms, “maritime network” scored less than maritime transport, trade, and traffic, shipping, port, or route, whereas “maritime transport” scored far below “road network,” thereby illustrating the paramount importance of roads for daily commuting and trucking. Such a situation echoes the work of Danisch et al. (2014) who in their analysis of word co-occurrences found that “global shipping network” occupied a peculiar, peripheral situation with regard to the graph theory community. As a matter of fact, many scholarly works using the term maritime (or shipping) network make no reference to graph theory per se, in contrast to road, railway, air, and even river transport where network analysis had become a very common approach since the 1960s in the social sciences (Ducruet and Lugo, 2013).

As pointed out by Lemarchand (2000: 1–2), “the literature on networks ignores maritime places [while] port and maritime actors do not refer much to the concept of network.” If the network traditionally describes technical systems made of material infrastructure, maritime routes exist on the map only so that the maritime network remains rather abstract, invisible, and decentralized, especially at the national scale where only a fragment of the network is perceived. The maritime network may refer to various realities according to different disciplines, such as trading linkages by sea organized by merchants in maritime history (Gipouloux, 2011; Tartaron, 2013), tactical or wireless communication networks between vessels in engineering, inter-firm alliances in maritime economics (Caschili et al., 2014), distribution of ocean carriers’ schedules, and physical flows of vessels between ports. With reference to the European Motorways of the Sea initiative, Baird (2010) even proposed to treat the floating deck of vessels just like road and rail infrastructure to favour integrated policies. In geography for instance, the maritime network had long been termed “system” (Bird, 1984: 26): “the ultimate system of maritime transportation is a true freedom of the seas whereby every port node can theoretically be linked to every other port node” (see also Slack, 1993).

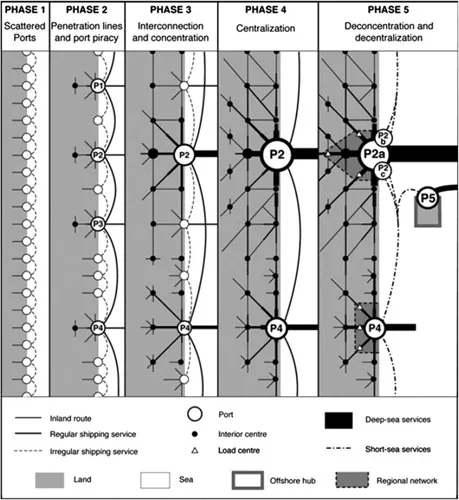

The concept of “port system,” suggesting linkages between ports was found in many works, but “in their preoccupation with the development of land communications (…) the authors neglected the development of maritime space” (Rimmer, 2007: 76). In addition, the port system concept was used interchangeably to describe multiple realities such as port (or maritime) range, region, façade, or seaboard, and mostly at the national scale, leading to confusion. The phased model of port system evolution proposed by Rimmer (1967) initially incorporated maritime linkages contrary to earlier models (see Figure 1.1), but without concrete empirical validation as subsequent works continued focusing on individual port traffics and port hinterlands. The classic distinction between a French school focusing on forelands and a Dutch school more interested in

Figure 1.1 Spatial model of the evolution of a port system including maritime linkages.

hinterlands (Weigend, 1956) led to distinct research pathways. For instance, the “port network” concept was proposed by Van Klink (1998) to describe the inland shift of port activities, but the same concept used in another context could also refer to a set of ports belonging to the portfolio of a given ocean carrier or terminal operator. When it comes to forelands, the French geographer André Vigarié (1979) proposed the concept of “port triptych” to think simultaneously the port itself, the hinterland (inland market area), and the foreland (overseas markets). Yet, out of 399 scientific articles published in major geography journals between 1950 and 2012, only seven mentioned foreland in their title, against 29 for hinterland; 12 mentioned “network” of which only five for maritime networks and seven for barge, hinterland, and other networks (Ng and Ducruet, 2014). Other concepts such as transport chain, logistics chain, commodity chain, and value chain became frequent to describe ports’ place in networks with a qualitative approach (see Robinson, 2002).

The emergence of a dedicated network vocabulary for describing maritime patterns and traffic came long after using more imaginary semantics. The French geographers René Perpillou (1959) and André Vigarié (1968), for instance, mentioned the constellation of ports and compared sea lanes to urban streets delivering flows of life in a city like arteries in a biological organism, respectively. Other concepts taken from other fields were gradually applied to maritime transport, such as corridor, loop, cycle, and hub. Graph-related concepts such as centrality and intermediacy were used about ports (Fleming and Hayuth, 1994) alongside studies of site and situation, carrier choice and selection factors, and port competition to explain the emergence of hubs at certain locations, but without yet applying network analysis to maritime flows, so that “a connectivity index is used for airports (…) but does not exist for seaports” (de Langen et al., 2007: 31). This deficit became a growing issue, especially given that “the structure of [maritime] networks evolves over time [and therefore] the position of ports as nodes in the network also changes over time (…) understanding these changes is crucial for analysing the competitive position and growth prospects of (…) ports” (de Langen et al., 2002: 1). The conceptualization of maritime transport as a network gave birth to many discussions that did not necessarily lead to empirical analyses of actual maritime flows, such as about security issues (Kristiansen, 2004; Angeloudis et al., 2007) or operations research on navigation safety, ship routing and scheduling, and optimization (Christiansen et al., 2013; Windeck, 2013). Maritime economics barely refers to either graphs or networks in its central focus on management, pricing, markets, and finance, which is also true of wider transport economics (Zwier et al., 1994; Brooks et al., 2002; Leggate et al., 2004; Stopford, 2008).

The diversity of maritime data analyses

Before analysing maritime transport as a network, graphical representations of maritime flows long remained broad estimates of amount and geographic distribution (Scarborough, 1908; Siegfried, 1943; Alexandersson and Norström, 1963; Central Intelligence Agency, 1973). Still in 2014, a geophysics paper reported “a lack of knowledge in the actual global distribution of the ships, i.e. vessel density, and its evolution over time due to economics or other causes” (Tournadre, 2014). This situation was already deplored in the 1940s when early economic geographers such as Ullman (1949) provided an innovative cartography of maritime routes connecting the United States, claiming that maritime flows were useful to “take the pulse of world trade and movement” (see also Figure 1.2). Such a call did not, however, have many followers. Foreign trade statistics served to analyze overseas connections or maritime forelands of single ports such as Toronto (Kerr and Spelt, 1956), Genoa (Rodgers, 1958), Hobart (Solomon, 1963), Victoria (Britton, 1965), Clyde (De Sbarats, 1971), Halifax and Saint John (Patton, 1961), Irish Sea ports (Andrews, 1955), and ports in the countries of Norway (Sommers, 1960), England (Bird, 1969; Von Schirach-Szmigiel, 1973), and Sweden (Von Schirach-Szmigiel, 1978). Such studie...