![]()

1 Pre-histories of mobility and immobility

The Bengal delta and the ‘eastern zone’, 1857–1947

When we met Mohammed Shamsul Huq in 2008, this spry, cheerfully toothless gentleman claimed to be 1081 years old. The son of a railwayman, he was born, he said, in 1901, near the Kidderpore2 docks in Calcutta. Fascinated by the great steamships that were repaired ‘[at] the ghat (jetty) just in front of our house’, as a young man he joined the British merchant marine and travelled the world, from Calcutta to London, taking in Rangoon, Colombo, Singapore, Jeddah, and ‘Africa’ along the way.

Shamsul’s gusti (or clan) was ‘Khan’, a patronymic that he dropped at some point in his life. In all likelihood they were Pathans from Afghanistan, who, in the winter months, plied their wares in upper India.3 Shamsul’s grandfather peddled warm clothing, travelling slowly from Punjab to Noakhali on Bengal’s southeastern seaboard. There, romance blossomed and brought his sojourning to a halt. He fell in love, married, and settled down with his Bengali bride in this humid, riverine tract – very distant, and very different, from the arid uplands of Afghanistan.

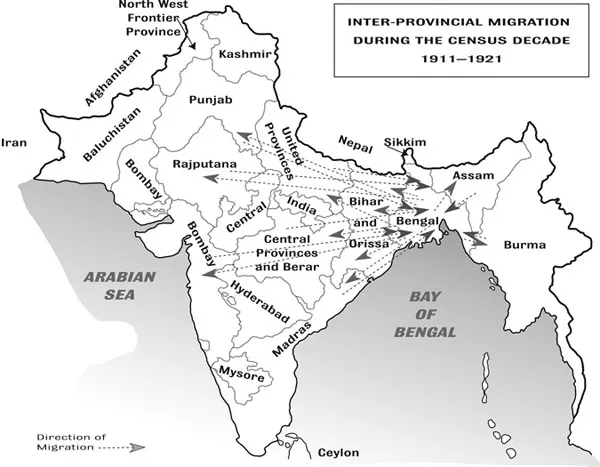

Not all his male children followed in his footsteps. Of six sons, three moved, albeit along different routes and with different purposes. One settled in the neighbouring town of Barisal to the west, and one (Shamsul’s father) moved north to Assam (see Figure 1.1). A third travelled further afield, and ended up ‘over there’, in London, where he married an English woman and set up a wine shop.4 The remaining three sons stayed on in Noakhali. Shamsul did not speak of his aunts, but, presumably, like his sisters and daughters, once married, they moved to their husbands’ homes, within the region itself.

For decades, Shamsul toiled in the sweltering heat of the ship’s boiler room, stoking the glowing furnace deep below deck, where he learned to speak a little English and ‘Laskari’, the pidgin dialect used by Indian crews. But he abruptly gave up his seafaring life during the Second World War, when his ship was bombed by the Japanese. After a spell on a hospital ship recovering from grave injuries, he swore he would never go to sea again. He returned to Kidderpore and set up a small tea stall.

Shamsul settled contentedly into this new life, chattering with his lascar customers by day and going home to his family at night. But the Calcutta riots of 1946 and the partition of India in 1947 tore his comfortable world apart. The aftershocks of these events forced him to move again and again in search of a safe haven. At first he and his family fled to Assam, where they had relatives, and where Shamsul’s father had worked as a railwayman. But they faced troubles there as well because they were Muslims, and Assam – now part of India – was not welcoming to Muslim migrants. In the 1960s the family was ‘pushed out’, Shamsul told us, and ‘told to go to Arabia’. Finally Shamsul found shelter of sorts in a small village in the district of Dinajpur in present-day Bangladesh, where the government of East Pakistan gave him a tiny plot of land as part of its measures to rehabilitate refugees. All five of his sons live in Bangladesh. His three daughters live nearby with their husbands, or with him, at the modest home where we met him.

Figure 1.1 Interprovincial migration during the census decade, 1911–1921.

What are we to make of Shamsul’s complex and peripatetic history? We will return to him again later in this book to tease out the many intricate processes that his life story illuminates. But here we must discuss the one bold theme at its centre, which must be the starting point of this chapter and, indeed, of this book: the widespread mobility in eastern India before the partition of 1947. To understand the scale and contours of the Bengal diaspora in the later 20th century, we must give up our nostalgic belief that partition ripped through a comfortably settled society.

Our arguments depart from existing scholarship on South Asian mobility in other significant ways. That scholarship is preoccupied, ever more overwhelmingly, with diasporas overseas. When scholars in the 1970s, many of them influenced by Marxism, began to write the history of the ‘taming’ of the ‘coolie beast’,5 a particular focus was indentured labour, famously described as ‘a new system of slavery’.6 Dominated, on the one hand, by labour historians7 and, on the other, by sociologists of labour diasporas,8 this has remained a powerful focus of study. In the 1990s, coinciding with the coming of age of the second and third generations in Asian diasporas in the West, anthropologists generated a lively body of work on ‘the cultural dimensions of globalisation’.9 Yet another, more recent, tradition has grown out of the fin-de-siècle historical fascination with ‘the Indian ocean world’, which has produced rich studies of merchant diasporas10 and the cosmopolitan port cities of the European empires. While each of these approaches has yielded important (and different) insights, they are united by their focus on diasporas overseas.

Where scholars have considered mobility within the subcontinent, a second characteristic reveals itself: the influence of compelling accounts of the progressive ‘sedentarization’ and ‘territorialization’ of South Asia in the colonial period.11 Keen to challenge the colonial shibboleth that Indians were a ‘stay-at-home race’, influential historians have shown that, on the contrary, before 1800, perhaps half the total population of the subcontinent was habitually itinerant for much of their adult lives.12 These patterns of mobility changed dramatically in the colonial era, and it is now widely accepted that British colonial policy settled Indians in place so that they could be more easily taxed, governed, and observed. While the ‘sedenterization’ thesis describes processes in the 18th and early 19th centuries, its influence is perceptible in studies of the century that followed. Even when historians recognize that between 1840 and 1940, the imperial state and economy created both pressures and opportunities for movement,13 they tend to emphasize emigration overseas,14 underlining the imperial state’s capacity to encourage, ‘or even forc[e], millions of Asians to move over long distances’, while ensuring ‘that others stayed firmly in place’.15 We are given a picture of a society in which internal migration had become rare and agrarian colonization an exceptional activity.

This emphasis on emigration overseas is problematic, both empirically and conceptually. Between 1859 and 1945, overseas migrants accounted for only a small proportion of the millions of South Asians on the move. The Imperial Gazetteer suggests that in 1901, at the height of the era of indenture, 1.37 million Indians had gone overseas to Ceylon, Malaya, and Burma, where they were most numerous, and also to the West Indies, Mauritius, Natal (in South Africa), and Fiji.16 Kingsley Davis, the pioneering demographer of the subcontinent, estimates that from 1926 to 1930, when overseas emigration peaked, some 3.2 million Indians travelled abroad, while 2.8 million returned.17 By contrast, the Census of 1921 recorded more than 15 million internal migrants,18 and this figure underestimated the true extent of internal movement for reasons that will be discussed later in this chapter. Moreover, after 1921, as it will show, internal migration grew by leaps and bounds. So the presumption that overseas emigrants are in some way representative of the modern migration process is misleading. To be sure, overseas emigration was a striking feature in some parts of the subcontinent,19 notably peninsular southern India, where internal migrations were indeed relatively rare and overseas migrations, at least before the Depression, were significant.20 Unquestionably, the history of these emigrants is complex and fascinating, richly deserving of the scholarly attention it has attracted. But emigration abroad was always only the most visible tip of the iceberg of human movement in the subcontinent.

This is no arcane statistical point. We raise it not to deny the significance of these journeys to faraway places, but to draw attention to the sheer volume of movement over shorter distances. Scholars have not paid sufficient heed to the scale, complexity, and impact of more local and intraregional migration in late colonial India, and this oversight has distorted our understanding of South Asia’s history of mobility in the late 20th century. This chapter tells the story of a dramatic rise in new forms of internal migration tied to the emergence of a novel economic and political order. It also uncovers the persistence of older patterns of mobility, albeit adapted to the new order.

It faces up, moreover, to the conceptual fallacy that true migration constitutes only movement across the borders of states, preferably across oceans. This fallacy unwittingly reproduces two misconceptions: first, that British India was a single, unified cultural and economic zone, and hence migration within it was not migration in a real sense, its social, economic, and cultural effects being minimal. Second, the emphasis on the crossing of formal political borders is a state- or nation-centred approach that most historians today rightly eschew.21 It implies that migration within a state and migration beyond it are inherently different activities, a proposition which this book will challenge.

Inevitably, then, a central focus of this work is the small journeys, often only from one locality to another within the region, which made up the vast majority of human movement in South Asia. These journeys were profoundly significant. Not only did they add up slowly, sometimes imperceptibly, to large changes in the character of regions, they also left legacies in their wake: connections, memories, and the knowledge, even hope, of potential for future journeys. They are important too for another reason: their links, still imperfectly understood, with cross-border ‘refugee’ movement after independence. This chapter identifies significant streams of movement that cut their criss-crossing channels through the deltaic region before the huge international upheavals of the mid- and late 20th century; and subsequent chapters will aim to illustrate the connections among these apparently distinct migrations.

There is a further point to be made here. Influential historians argue that ‘in the 1930s and 40s, patterns of inter-Asian migration broke down and went into reverse’,22 and they stress that, for migrants, ‘the middle...