Internal meanings

In the opening sequence of Abohoman (The Eternal, 2010), ailing film director Aniket Mazumdar muses, ‘What is a film all about?’ Flanked by distant blue mountains on all sides, he tells his son Apratim about celluloid latitude implying range, scope and tolerance. His drifting mind considers how on digital mode he can erase and record, start anew at any point. Longevity of film and impermanence of the digitised image become metaphors of life, memory and meaning.

A director’s film reflects the director’s personal creative vision – that of the primary author. The auteur expresses his thoughts and feelings about a subject matter and offers a worldview. From the time Truffaut advocated this theory, a director’s distinctive style or consistent themes are considered defined influences, unmistakable in a body of work. An auteur needs a considerable body of work, which can be analysed for themes and concerns and display a distinct style immediately recognisable. ‘Over a group of films a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature’, Andrew Sarris wrote as he further developed the auteur theory.1

A film-maker must offer a group of films with a certain characteristic of style, a body of work that can be analysed, and most importantly offer subtextual or internal meaning in the works. The third premise is considered the ultimate glory of cinema as an art as Andrew Sarris expatiates:2

Internal meaning is the combination of contradictions: the director’s world view combined, meshed with the film’s subject matter and all other contributing factors of the film. A meaning and outcome ultimately derived from the director. It is the director’s attempt to create a whole from significantly disparate and opposing meanings and influences.

Auteur theory has generated debate over the years, particularly with Pauline Kael or Peter Wollen maintaining an oppositional idea that film-making is a collective process. John Caughie, in turn, privileges the critical spectator who reads the ‘directorial subcode’.3 More recently, Janet Staiger reiterates the function of the auteur through ‘the authoring choice’.4 Moreover, Richard Dyer posits that the star actor is also auteur and David Kipen argues that the screenwriter is the true auteur of a film.5

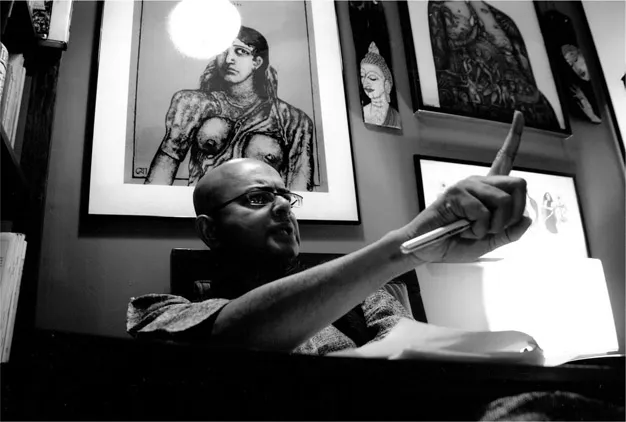

Figure 1.1 Rituparno Ghosh at a script discussion in his study

In the light of theoretical arguments, Rituparno Ghosh’s filmography invites assessment as an auteur’s work. Almost all of Ghosh’s 20 films are

Figure 1.2 Ghosh with the author Sangeeta Datta on the sets of Raincoat

written by him, occasionally co-written (Sob Charitro Kalponik and Arekti Premer Golpo); most of his films are either direct adaptations of or inspired by literary texts. He stars in his last two films (Chitrangada and Jeeban Smriti) as well as in two films by other film-makers (Arekti Premer Golpo and Memories in March). However, the vision informing the work is unmistakably Ghosh’s alone. It is this individual style and treatment he brought to his films that attracted both the stars and his audience. He had the persuasive power to bring back iconic female stars of Bengali cinema: Aparna Sen, Sharmila Tagore, Rakhi, and Madhabi Mukherjee. Popular Tollywood icon Prosenjit Chatterjee delivered impressive performances in his films. From the Hindi film industry, his scripts fetched Kirron Kher, Ajay Devgn, Aishwarya Rai, Jaya Bachchan, Amitabh and Abhishek Bachchan, and Manisha Koirala to work in the poorer conditions of Tollygunge studios. In fact, the commercial Bollywood world held Ghosh in certain regard and this facilitated revolving doors into their mutual worlds. In other words, Ghosh’s films are always star driven.

This chapter will explore Ghosh as an auteur whose work displays repeated themes, narrative patterns and evolving ideas that run through a number of otherwise disparate works. Co-ordinating all stages of production and well abreast of his audience, he possesses a personal style and an ‘interior voice’ or subtext. Ghosh, as writer–director–actor–star, defines the auteur who offers a well coded visual, literary and performance aesthetic. A leading voice in Bengali culture, straddling various media worlds as writer, magazine editor, television host, and fashion icon, Ghosh holds the position of director as star who later inserts himself as actor in his narratives.

This chapter will attempt to search for the auteur vision in Rituparno Ghosh’s 15th feature film Abohoman. It will look at certain themes – the middle class family space, evocation of mythology and language, film within film, film as metaphor of life, and the director’s increasing obsession with death. Holding Abohoman as its core text and transition point, the chapter will allude to Ghosh’s filmography before and after this film: Unishey April, Utsab, Bariwali, Chokher Bali, Raincoat, The Last Lear, Arekti Premer Golpo, Chitrangada, and Jeeban Smriti. Abohoman marks a significant transition point, as the chapter would show, from Ghosh’s early linear narratives towards a more complex auteur vision exploring fluid time, space, artistic/performance identity, and the jagged contradictions of the artistic process. Abohoman demonstrates the convergence of early themes and points to nascent ideas that will evolve more fully in his later work.

The normative family and dinner table conversations

Strongly influenced by Satyajit Ray’s films (particularly his last films Ganashatru/Enemy of the People, 1989; Shakha Proshakha/Branches of a Tree, 1990; and Agantuk/The Stranger, 1992), Ghosh’s early films are dialogue heavy and largely static. Depicting the reality of middle class lives and interiors and questioning the moral world of the family as an institution, Ghosh often exposed the duplicity implicit in apparent liberal homes of the Bengali bhadralok. Ghosh’s feminist concerns govern the early films with women-centric narratives and the discontent/despair of the normative family. Ghosh’s psychological realism sets characters firmly within the architectural space of the home.

Ghosh’s early works reflect and are products of middle class liberalisation; urban mobility, aspirations and contradictions are reflected in domestic interiors which form the site of chamber dramas. Within these Bengali homes, a central space is the dining table around which characters gather and converse. But the space for warmth, nurture and conversation is often turned into a political space for unlikely confrontation between parents and children or between husband and wife. Often critiqued for his demonstration of middle class6 consumerist aspirations, Ghosh in fact offers the apparent potential comfort of family space only to disrupt/dislodge it with conflict, challenge or confession.

The family home in Abohoman reveals subtle power imbalances. The discreet upper middle class home houses the film-maker Aniket (Dipankar De), his wife Dipti (Mamata Shankar), who has abandoned a potential acting career, and son Aniket (Jishu Sengupta), who is now a digital film-maker. The dining space, in director Aniket’s home, features several times in Abohoman: at first, not as the centrifugal nurturing space but that occupied by the marginal and macabre. Aniket’s senile mother (Shobha Sen), tended by her nurse, has her meal at the table, unaware of her son’s demise. Srimati/Shikha Sarkar (Ananya Chatterjee), who has been instrumental in causing a rift in an otherwise happy family, arrives to pay homage to her departed mentor and is seated at the dining table.

Later, a flashback sets out a perfectly normal dining scene. Aniket reads a book during his meal, wife Dipti and son Apratim converse about the concept of sophistication and the lack of it (Aniket’s wife and lover are polarised on this grid repeatedly). Dipti talks of her faith in the new actress Shikha, who is uneducated but has an arrogant spirit. She reminds Dipti of her younger self, as she proceeds to put her trust in the newcomer.

The lighter mood in this sequence is soon replaced by a rather tense dining table scene when much has changed. Dipti is now aware of her husband’s relationship with Shikha and his regular excuses about coming home late. A phone call disrupts the scene and Aniket retreats to the bathroom to talk. An unnerved Dipti overreacts and lashes out at her mother-in-law while Apratim tries to calm her down. Revelation of lies, deceit and unfaithfulness compel Dipti to confide in her teenage son. In the third scene, the bare dining table is no longer the sustaining family space. Aniket is absent; a lonely Dipti sits quietly at an empty table while her son approaches to comfort her.

Troubled parent–child relationships are explored repeatedly by Ghosh in his films, starting from the Bergman-inspired Unishey April, in which a daughter (Debashree Roy) holds her ambitious mother Sarojini (Aparna Sen) guilty of her father’s death and has to resolve unstated issues. The night Aditi plans to stage her suicide, her mother returns home unexpectedly. Mutual issues are resolved while trying to stir up a meal and discussing recipes across the dining table. One of the key scenes in Asukh is set across father (Soumitra Chatterjee) and daughter Rohini (Debashree Roy) sharing a meal. As Rohini’s father talks about her mother’s recurrent illness, a normative scene is fractured by Rohini’s growing suspicion about her father’s sexual life. The four walls of the dining room become the site of deep-seated suspicion and inarticulate questions. Her dark, airless and claustrophobic room, on the other hand, mirrors her clouded mind and her eye infection prevents clear vision. In both these films, the possibility of young romantic love is threatened/negated/subsumed by more personal issues of family and identity, which need addressal.

In Utsab, in an apparently happy family reunion during festive time invested with mythological overtures (that Goddess Durga leaves her heavenly abode with her family of four children to visit her father’s house on Earth), a dark secret of family incest is revealed. While others seem uncomfortable and unable to deal with Parul’s (Mamata Shankar) breakdown, her teenage son (Ratul Shankar) comes forward to offer sympathy and comfort. The son already demonstrates a forbidden affection for his cousin sister, an excess played out in furtive light and shadows, which the narrative finds difficult to contain. These women-centric interior dramas explore bonding, seclusion, hysteria, and recovery, evoking Pedro Almadovar’s feminine worlds in urban spaces (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, 1988; All About My Mother, 1999).

This everyday space of the dining table is rather volatile in Chitrangada. The first family dinner scene is set in a half-lit room with three characters at the dinner table. Choreographer Rudra (Rituparno Ghosh) invites his mother to his new stage production. He has long given up hope to see his father in the audience, knowing his reluctance to watch him dance. In the next scene, Rudra is more rebellious, openly talking about his intentions of leaving home for a sex reassignment surgery. Facing his mother’s stifled anger, he admits he has been a perennial embarrassment to his parents. While his father sits defeated, his mother struggles to understand Rudra and assures him he need not leave home.

In a later scene, preoccupied parents eat hesitantly, confessing that they should have recognised the truth about their son a long time ago. These scenes of huge upheaval set over the everyday act of family meals, lit in half shadows, link the mythological to the familiar/real. They are archetypal middle class parents, who painfully reconcile to their son’s radical choice. Ghosh brings the political debate of gender and identity directly into a central familial space, first disrupting this site of nurture, then offering possible resolution for the most fraught exclusion. Ghosh’s physiological and psychological treatment follows Almadovar in exploring the contradictions of hospital/clinical spaces (Talk to Her, 2002; The Skin I Live in, 2011).