![]()

1 Origins of the Project

As with many feminist projects, this study of women who combine Christianity and Goddess Spirituality began with my own experience. Raised in a religious evangelical Protestant family, I was taught that God was a father-figure, a powerful king on a heavenly throne, with a son, Jesus Christ, who, while more approachable, also partook in his father’s royal and potent attributes. Unlike Catholic girls of my generation, I had no image of Mary or other women saints as quasi-divine female figures to relate to or venerate. The minister and all the church elders and deacons were men; women were permitted to sing in the choir, play the piano, teach children in Sunday School and provide food for church social events, not to lead, preach or teach adult members of the community. "Man," according to the King James Version of the Bible used in church, was made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1: 27). Whether or not women reflected the divine image was not discussed, although Eve’s sin, and the resultant fall of “man” into a chronically sinful state, made women’s status before God problematic from the start, to my youthful mind.

Like many other adolescents, I drifted away from the church for a time in my teens, only to return to the familiar support of Christianity as a university student. However, the churches I was drawn to were more liberal than the Baptist community of my childhood, and my studies in religion introduced me to other religions and forms of Christianity. In my early twenties, I converted to Catholicism, which, in the late 1970s, seemed ripe with post-Vatican II possibilities. My graduate studies in the 1980s included courses in feminist theology and biblical studies that not only opened up new roles for women and new insights into women’s roles in the Bible but also the notion of the female divine as expressed in the emergent Goddess movement,1 and even in the Christian tradition itself.

As someone whose family tradition and personal history is Christian, feminist theology has been a key aspect both of my spiritual and academic formation. Although I am not a theologian but a biblical scholar, I am a feminist biblical scholar, and these traditions of feminist scholarship have made Christianity a (sometimes barely) viable religious option for me. However, as a scholar of religion, and as a Christian-identified feminist, I have also been attracted to Goddess Spirituality, which, as I shall discuss in chapter 2, is a movement that developed in tandem with feminist theology as parallel religious expressions of Second Wave Feminism. However, despite their common origins, Christian feminist theology and Goddess Spirituality have sometimes coexisted in an uneasy relationship,2 at least in academic circles.

As daughters of the same mother (see chapter 2), Goddess Spirituality and feminist theology are bound to share some family resemblances. Melissa Raphael notes that if Goddess religion is post-Christian, “it means that post-Christian women and men are still in varying degrees of serious and sharply critical engagement with the Christian tradition to which they may have once belonged.”3 Raphael has also noted that as spiritualities, the differences between thealogy (discourse on the Goddess) and Christian feminist theology may be more of “emphasis or degree” than of kind, citing Linda Woodhead:

not only is there considerable overlap between feminist theology and much contemporary Christian theology and spirituality that is not explicitly feminist, there is also considerable overlap with thealogical [Goddess] spirituality.4

Woodhead, a sociologist, finds the distinction between post-Christian feminist spirituality (which is mostly Goddess-oriented), on the one hand, and liberal Christian feminist theology, on the other, to be overdrawn:

I believe that the only difference. . . is that reformist feminist theologians are happier than post-Christian ones to use the Jewish and Christian traditions as a fruitful source of symbols and stories, and sometimes they are prepared to remain within the church. Beyond this, their spiritualities seem to me identical and equally post-Christian.5

For Woodhead, the feminist theology of Rosemary Radford Ruether is indistinguishable from the Goddess thealogy of her spiritual feminist colleagues, citing “Ruether’s emphasis on women’s experience, her discarding most of Christian tradition bar the prophetic one, the use of non-Christian traditions in her work of the mid-1980s, her description of the divine as ‘Primal Matrix,’ and her foundational ecofeminism.”6 As Raphael notes, Woodhead’s assertion that Christian feminism and Goddess Spirituality are virtually identical is an overstatement, but the “foundational impetus” of the two movements is the same:

Both aim to retrieve female authenticity and history; both believe that one can be both religious and a feminist and that, indeed, religion, within a feminist paradigm, is politically as well as spiritually liberative. Reformist and radical religious feminists share much of the same leftwing ecological, anti-militarist and nurturant emphases.7

As I shall discuss in more detail in chapter 6, another feature shared by Goddess and feminist Christian spiritualities, thealogy and feminist theology is a focus on female images of divinity, for thealogians, the Goddess/es, for Christian feminist theologians, Sophia and other female personifications of the divine.

In the past fifteen years, I have been intrigued by what Goddess scholar Johanna Stuckey calls “Revolutionary” feminist theology, an approach to Christian feminism where female language and images for the divine are routinely used, and where Goddesses from other religious traditions are sometimes invoked.8 This trend challenges any neat distinction between feminist theology and thealogy. Stuckey notes that one of her students called this emerging tradition “Pagan Christianity”:

A ritual example was reported from a Women-Church group; the ritual begins with a calling down of the spirits of the four directions, a borrowing from Wicca and other traditions; continues with the reading of Bible selections that praise Earth; and ends with worshippers weaving a communal web. . . . Such a ritual certainly pushes Christianity to its limits.9

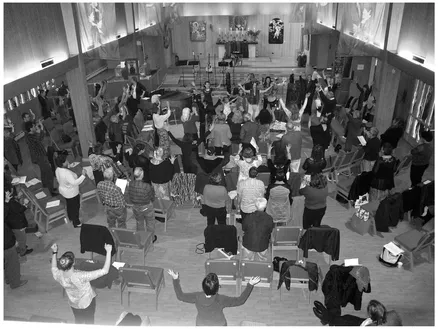

I have personally attended a Croning Ceremony—a Wiccan/Pagan ritual— for an administrator of a Christian seminary and have been surprised by a birthday party with a Croning theme held by Christian women in my honor. A United Church seminarian (now ordained) mentioned to me that she started each day by drawing a Goddess oracle card and reflecting on its meaning for her. A Catholic couple, very involved in their local parish, told me that they had enjoyed a Winter Solstice party organized by a friend. I’ve attended a lecture on ecological theology delivered by a Catholic sister to a Christian feminist organization where she mentioned the “Goddess times” of prehistory, where everyone knew what she was talking about, and nobody took exception. A Facebook friend who is an Anglican priest expressed her excitement about visiting an Italian city with a temple of Minerva that was later dedicated to Mary, like many other Goddess temples. A young Catholic mother of two small sons confided in me that she had come to realize that the Canaanite-Israelite Mother Goddess Asherah had always been her true deity, because Asherah was a Goddess of nurture and motherhood. I have joined numerous listservs and Facebook groups frequented by Goddess Christians, Christo-Pagans, and Christian Witches and Wiccans. I have visited herchurch (Ebenezer Lutheran) in San Francisco,10 a church belonging to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, whose signage proudly proclaims that “God/dess loves all her children,”11 and where a Goddess rosary service is held every Wednesday evening. On my first visit there for a conference, I was surprised to meet three other Canadian Prairie women, one a United Church minister and two who worked in a United Church college, who were drawn there by the Goddess scholar and theologian Carol P. Christ, whose Goddess Pilgrimage to Crete we had all experienced. These kinds of experiences, and my own natural inclination to blur the lines between Christian feminism and Goddess Spirituality, are the origins of the research project reported on in this book.

Figure 1.1 Christ Sophia Mass, herchurch. Photo credit: Alice Heimsoth, www.aliceheimsoth.com/

While some of the people mentioned above may be somewhat aware of developments and debates within academic Goddess studies and feminist theology, as the following pages will show, this is a nonacademic phenomenon, prompted by the individual spiritual, psychological and social needs of people of different ages, classes, professions, ethnicities and religious backgrounds. Some identify strongly as Christian; others, less so, although all self-identify as blending Christianity and Goddess Spirituality as they define them. It is a spirituality dominated by women, although men are also involved. Although the example of a “Pagan Christian” ritual cited above by Johanna Stuckey above dates back before 1992, this phenomenon has received very little academic attention or analysis, but like the references by Carson (see n. 9 above) and Stuckey, it is noted in passing as an interesting peculiarity of some feminist Christian groups.

This study focuses on what I have started to call Christian Goddess Spirituality (CGS), a development that, as Stuckey observes, might be so “Revolutionary” that the religion transformed by it might not still be recognizably Christian,12 at least in the eyes of more conservative Christian observers. Although CGS also has implications for Goddess Spirituality and related traditions (e.g., Neopaganism, Wicca), here, CGS is considered primarily as a phenomenon within Christianity. However, the fusion of Christian and Goddess Spiritualties also has had an impact on non-Christian feminist spirituality, since, as I shall argue later, Goddess-worshipers have often constructed Christianity (with some justice) as the diametrical opposite and enemy of the Goddess, to the point that some refuse to admit the possibility that CGS is a valid spiritual path, or that it is even possible. In addition, Christian and Jewish images of the divine such as Sophia, Shekhinah, the Virgin Mary and even Mary Magdalene have found their way into Pagan Goddess pantheons.

Previous Research

A great deal of research exists on the interrelated phenomena of Goddess Spirituality, Neo-Paganism, Wicca and Witchcraft.13 While such studies often note that, not surprisingly, the majority of members of these movements have Christian or Jewish backgrounds, it is generally assumed that those who belong to these traditions have definitively and permanently rejected Christianity (or Judaism). ...