![]()

1 The impact of the redistribution of Partition’s evacuee property on the patterns of land ownership and power in Pakistani Punjab in the 1950s

Ilyas Chattha

The mass displacement created by the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 was phenomenal in its scale and impact. Around 20 million people were displaced by Partition, with Hindus and Sikhs migrating to India and Muslims migrating to Pakistan. Despite the scale of this refugee crisis, historians have only just begun to gauge its larger socio-economic and political impacts. This chapter looks at the history of the key province of the Punjab in Pakistan in the early post-independence period. It examines how the redistribution of evacuee land – the land abandoned by departing Hindu and Sikh landlords – impacted on patterns of land ownership and power in post-Partition West Punjab. A number of important points emerge, namely that the process further entrenched the larger landowners’ power and that the aftermath of Partition could be as disruptive for indigenous populations as for refugees. Evidence of the disruption is clear in the case of local tenantry who faced hardship and dislocation because of the migration of their former Hindu and Sikh patrons when their holdings were allocated to resettle incoming Muslim refugees. The chapter sheds light also on the lengthy process of rural resettlement, the land grab situation, and on the factionalism which undermined the Punjab Muslim League. Finally, the chapter identifies the quest for a more egalitarian society raised by Mian Iftikaharuddin (1907–62), the first Minister for Refugee Rehabilitation (1947–8), through his proposals for land reforms. Their rejection was to have long-term consequences for political and socio-economic development in the Punjab, the core province of Pakistan.

Recent historiography has highlighted the profound impact of the mass influx of refugees on state formation and its legacies for ethnic and religious nationalism in South Asia’s politics and culture.1 One of the striking features of the studies is the consideration of the variety of ways in which refugees were assimilated into local communities and the contrasting ways in which they collectively emerged as a distinct political group.2 But focusing solely on the urban experience overlooks the experience of rural residents who made up the vast majority of the population. Moreover, research on rural resettlement has largely focused on the Indian experience.3 Most historians now acknowledge that one of the most significant consequences of the refugee crisis was that it fundamentally unbalanced the entire substructure on which Pakistan had been built. Early work of Ayesha Jalal and Ian Talbot, and more recently Farzana Sheikh, has persuasively suggested how the institutional balance of power quickly shifted in favour of the better-educated migrant bureaucracy and the well-entrenched military establishment in the early years of Pakistan’s history.4 Hamza Alavi’s influential article on the state in post-colonial societies focussed on Pakistan and Bangladesh and pointed out that the new state inherited a strong military and bureacrative administrative apparatus. The ‘centrality’ of the post-colonial state, which evidently follows from these propositions, implies the ‘centrality’ of the state bureaucracy, which Alavi dubbed an ‘oligarchy’.5

Partition changed everything. Remarkably, historians have yet to appreciate the extent to which the reallocation of refugees impacted landholding and political power. Land, which in Punjab’s agrarian society was a major source of income, power, and status, was concentrated in a few hands. Both the pattern of ownership and the size of holdings varied from locality to locality. How strongly entrenched the big landowners were in the Punjab at the time of Partition is shown by the fact that they owned more than 50 per cent of the cultivable land. In some instances, the ownership concentration extended over hundreds of hectares.6 However, landowners’ role in politics and economic policy was much broader than the mere possession of land. Colonial rule in the Punjab sought ways to reinforce the rule of the ‘landed gentry’ in pursuit of political stability by granting large jagirs (land grants) to them from the late-nineteenth century onward.7 Members of this group dominated the cross-communal Unionist Party, founded in 1923, that had governed the province since the 1920s.8 Despite tremendous socio-economic and political change, they reproduced their power.9 In the mid-1940s, many of this party’s landlord leaders shifted their allegiance to the All-India Muslim League, founded in 1906, considering it a better vehicle for their interests.10

Despite many detailed studies of the ways in which the Punjab’s traditional landowners controlled provincial politics, relatively few historical studies reach beyond the 1940s. Yet, the legacy of Partition for democratic practices arising from landlord retrenchment, the mishandling of evacuee property, factionalism, centre-province relations, and the increasing links between the refugee sections of the bureaucracy and migrant landlords, deserves special attention. This chapter suggests some of the ways in which the refugee crisis and the land grab situation in the Punjab undermined the attempt to establish democratic norms in early post-independence Pakistan. This has not been previously considered at length. Conventional accounts in nationalist historiography ignore local developments in their focus on personalities. However, the tension between the centre and the provinces, and the capture of the state by the bureaucracy and its landlord allies can only be fully comprehended through reference to studies of the local areas. Moreover, an assessment of the larger consequences of Partition is essential for historians to get down to the grass-roots level, not only as a study of agrarian history, but for a better understanding of the nature of socio-economic and political developments in Pakistan’s early history. While the focus is on West Punjab, this will be done through addressing major themes arising from the impact of mass displacements. It also represents a useful contribution to understanding the Indian refugee experience by highlighting how the failure to introduce tenancy and land reforms in the early years ensured that the Punjab followed a vastly different socio-economic and political trajectory from its Indian neighbour.

Certain points emerge. The refugee crisis opened up new opportunities for big landowners in West Punjab as they further tightened their grip over rural society and provincial politics through refugee resettlement. Some benefited by grabbing additional land, either by purchasing it at nominal prices from departing or incoming refugees or unlawfully occupying evacuee property; while some replaced the migrating Hindu banias (moneylenders) as the main source of rural and agricultural credit. According to one report, out of a total of 6 million vacated acres, over 1.8 million in West Punjab alone were ‘illegally occupied by local residents’.11 Hundreds of thousands of existing tenants faced economic hardship and dislocation as their holdings were allocated to incoming refugee cultivators. The latter were smallholders compared to the migrating Hindu and Sikh landlords. The possibility of land reform was raised by Mian Iftikaharuddin, who came from a wealthy and politically prominent Punjab family, and owned the Pakistan Times. Calls for land reform were not only met with stiff resistance by the ruling landowning politicians, but they also used their political clout to focus the state’s attention on ‘nationalisation’ of the private estates of powerful ‘rival’ politicians, most notably the last Premier of colonial Punjab, Sir Khizr Hayat Tiwana (1900–75, Premier 1942–7). This was to have corrosive consequences for the democratic system.

Agricultural refugees’ dispersal and resettlement

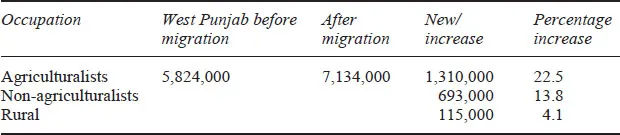

In April 1948, the West Punjab authorities completed a refugee census and revealed that 5.5 million Muslim refugees had arrived in the province, representing over 28 per cent of the population.12 The exchange of population increased the rural population of West Punjab from 5,841,000 to 7,134,000, an increase of no less than 22 per cent, as Table 1.1 illustrates.13 Over 75 per cent of them were ‘agriculturalists’ or ‘rural’.

This presented an unprecedented and unanticipated problem for the new government. Initially, an ad hoc ‘Guzara Scheme’ (a temporary allotment) for the redistribution of land for the first two rabi (spring) and kharif (autumn) harvests was drawn up. The idea was that pushing refugees from camps to villages would not only save the government huge amounts of money but would assimilate them into the economic life of the villages. The authorities were particularly anxious that abandoned fields should not lie uncultivated during its incoming rabi crop and that the labour of refugee cultivators would avoid a food shortage. Another concern was the fear of illegal occupation of evacuee land. The temporary allotment, therefore, was based on ‘an equal distribution of land’, regardless of the land left by an individual in India. A fixed area of land was allotted to each family of five. The average unit was fixed at between six and eight acres in irrigated areas and up to 12.5 acres in non-irrigated areas. In this way, by the end of 1948, an official survey claimed that about 3.95 million refugees (90 per cent) had been dispersed on 3.39 million acres of evacuees’ land in West Punjab.14 While the refugee cultivators were quickly dispersed to villages, in actuality the process of settlement was much more difficult and lasted a lot longer.

Table 1.1 Exchange of population in rural West Punjab

An official survey in 1948 calculated that nearly six million acres of ‘cultivable’ or ‘revenue paying’ land was abandoned in West Punjab.15 A major part of the land was, however, under Muslim tenant cultivation. As Table 1.2 indicates, more than 50 per cent of the vacated land was under cultivation by ‘tenants-at-will’ who had no security of tenure or legal and heritable rights.

Although the payment of rent varied from area to area and even from locality to locality, sharecropping was the most common method of payment of rent: landlords and tenants shared the crop on a 50–50 basis, although tenants were also required to render services of various kinds.16 Without any formal contract tenants were liable to eviction without compensation, although many families had been cultivating the same land for generations on customary arrangements. As a result, they did not abandon their holdings willingly.

Impact of refugee settlement on local tenantry

The impact of Partition could be as profound for those who did not migrate as those who were uprooted, as Joya Chatterji’s recent work shows with respect to the impact on Bengali Muslims who did not cross to East Bengal.17 In West Punjab, a large number of local tenants had to pay a heavy price as their holdings were either greatly reduced, or they were forced to abandon them completely in favour of peasant refugees. The resulting economic and social deprivation experienced by tenant families forced many younger male members to look for seasonal or permanent employment in nearby cities.18 Many others were compelled to become casual labourers. A large number of them, however, turned to local landlords for employment. Hundreds of thousands became internally displaced, while a large number migrated to kacha alaqa (uncultivated areas); about one million people were relocated to unused state lands in southwest Punjab.19

Table 1.2 Land ownership and cultivation patterns in West Punjab in 1947

Land owned/cultivated | Total acreage |

Revenue paying land vacated by evacuees | 6 million |

Owned and cultivated by non-Muslims | 2.7 million |

Owned by non-Muslims, but cultivated by Muslims | 3.1 million |

As Table 1.2 shows, with such a large concentration of holdings in the hands of existing tenants, the state was in no position to eject them completely. Attempts to do so would spark both an economic and a political crisis. Against this background, local tenants were initially directed by revenue officers to pay their rent to the ‘new refugee allottee landlords’, instead of abandoning the land. This was not as simple as it sounds. In many instances tenants refused to pay the refugees, seeing it as the first step to their eviction. In 1950, in Lyallpur district 1,267 tenants were ejected from the land due to non-payment of rent. By early the following year tenant protests had spun out of control and hundreds were arrested in various parts of the province. Intelligence reports recorded that further evictions and arrests could lead to violent large-scale protests and mass protests aimed at the government. Assessing the consequences of the growing peasant movement, the au...