- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1995. The WWW, a global information system which revolutionized the world of information search and browsing via the Internet, was a new phenomenon in the 1990s. This book acted as an authoritative introduction to the concepts and design. It includes a brief history of the origin of the www and information on running pages in HTML as well as specific case studies in projects from academic and commercial projects. A fascinating insight into the early days of widespread internet use, this look at a new communication mechanism showcases the discussions underway at the time about the uses and future of the www.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The World Wide Web by Mark Handley,Jon Crowcroft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Information Highstreet – introduction

The Internet is the Information Superhighway; it has become a cliché to say so. However, before embarking on a drive around the World Wide Web (WWW), it is important to understand how the roads themselves work (and to understand who pays road tax).

The Internet is undergoing a stormy adolescence as it moves from being a playground for academics into a commercial service. With more than 50 per cent of the network being commercially provided, and more than 50 per cent of the subscribers being businesses, the Internet is now a very different place from what it was in the 1980s. Growth has occurred most sharply in Europe, and in the commercial sector in the past two years. This has led to the critical problem of dealing with change. And change must be dealt with. Along with routing and addressing, there is also a crisis in security (or lack of it) and in accountability. These factors have led to the most interesting debate in the history of communications, as political, economic and technical concerns become inextricably intertwined.

There are two aspects of the technology. The first is host software (applications and support), which forms what one might call the “Information Services”. The second is network support, which is the access and transfer technology used to move the information around.

First, a brief history of the Internet will give some clues as to its success, and will give some context to understanding how WWW works and fits together with the rest of the Information Highstreet.

Internet history

The Internet started life as a report written by the Rand Corporation for the US government in the 1960s. This outlined the very modern view of information supplanting material goods as the commodity of the coming century.

The US government agency ARPA, the Advanced Research Project Agency, invested several billion dollars in developing “packet switching networks” through the early 1970s. Initially, the customer for these was the US Department of Defense. However, many of the researchers contracted to carry out the work were academics, who became enamoured of the test systems they built. Initially, the research network was called the ARPANET, later renamed the Internet.

By the very early 1980s, two other important pieces of technology had been developed. First, the workstation/server system was starting to emerge as the way to provide cost effective computing to the desktop. Secondly, the Ethernet local area network was broadly accepted as the way of providing communications between the desktop and server computers in the same organization. The same researchers used all these systems for computing, local and national (US) communications.

A curious footnote to this history was that the US government funded most of the initial implementations of the Internet technology on the basis that it would be made freely available to others. This was in direct contrast to the expensive communications solutions provided by computing and telecommunications companies that conformed to international standards promulgated by the ITU (International Telecommunications Union) and ISO (International Standards Organization).

By the late 1980s, a large proportion of universities and research laboratories in Europe and the USA had access to the Internet through largely government-subsidized network links leased from the public network operators. However, this changed rapidly, so that now many Internet connections are paid for directly by subscribing organizations.

On the standards front, it became obvious that people were “voting with their feet”, but that the Internet protocols (the communications languages used to glue all this together) needed to have a more acceptable status. Hence, the Internet Society, an international not-for-profit professional body formed to allow individuals, government agencies and companies to have a direct say in the direction that the protocols and the technology could move, was formed.

This is now very much the state we are in today and, except for one other thing, would not really explain the recent massive growth in interest in the Internet. That one thing is the World Wide Web, of which more in a moment.

Hosts, networks and routers

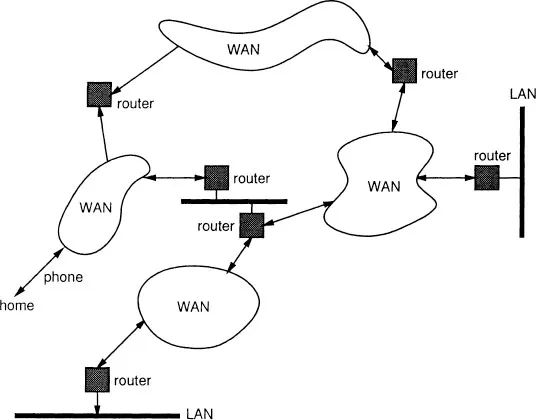

The components that make up the Internet are threefold, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. First, there are hosts, the workstations, PCs, servers, and mainframes on which we run our applications. Then there are networks, the local area networks (Ethernets), point-to-point leased lines, dial-up (telephone, ISDN, X25) links, that carry traffic between one computer and another, and finally there are routers. These glue together all the different network technologies to provide a ubiquitous service to deliver packets (a packet is a small unit of data convenient for computers to bundle up data for sending and receiving). Routers are usually just special purpose computers that are good at talking to network links. Some people use general purpose machines as low performance (low cost) routers, e.g. PCs or Unix boxes with multiple local area network (LAN) cards or serial line cards or modems.

Figure 1.1 A piece of the Internet.

Names, addresses and routes

Every computer (host or router) in a well run part of the Internet has a name. The name is usually given to a device by its owner. Internet names are actually hierarchical, and look rather like postal addresses. Jon’s computer’s name is

waffle.cs.ucl.ac.uk. We allocated it the name “waffle”. The department we work in called itself “CS”. The university it is in called itself “UCL”. The academic community called themselves “ac”, and the Americans called us the “UK”. The name tells me what something is organizationally. The Internet calls this the Domain Name System. Names in this system are “case insensitive”, which means that it makes no difference whether you give them in capitals or not.Everything in any part of the Internet that needs to be reached must have an address. The address tells the computers in the Internet (hosts and routers) where something is topologically. Thus the address is also hierarchical. My computer’s address is 128.16.8.88. We asked the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority) for a network number. We were given the number 128.16.x.y. We could fill in the x and y how we liked, to number the computers on our network. We divided our computers into groups on different LAN segments, and numbered the segments 1–256 (x), and then the hosts 1–256 (y) on each segment. When your organization asks for a number for its net, it will be asked how many computers it has, and assigned a network number big enough to accommodate that number of computers. Nowadays, if you have a large network, you will be given a number of numbers. The task of allocating numbers to sites in the Internet has now become so vast that it is delegated to a number of organizations around the world – ask your Internet provider where they get the numbers from if you are interested.

Everything in the Internet must be reachable. The route to a host will traverse one or more networks. The easiest way to picture a route is by thinking of how a letter gets to a friend in a foreign country. You post the letter in a postbox. It is picked up by a postman (LAN), and taken to a sorting office (router). There, the sorter looks at the address, sees that the letter is for another country and sends it to the sorting office for international mail, where a similar procedure is carried out. And so on, until the letter gets to its destination. If the letter was for the same “network” then it would immediately be delivered locally. Notice the fact that each router (sorting office) does not have to know all the details about everywhere, just about the next hop to make. Notice also that the routers (sorting offices) have to consult tables of where to go next (e.g. international sorting office). Routers chatter to each other all the time figuring out the best (or even just usable) routes to places.

The way to picture this is to imagine a road system with a person who is working for the Road Observance Brigade standing at every intersection. This person (Rob) reads the names of the roads meeting at the intersection, and writes them down on a card, with the number 0 after each name. Every few minutes, Rob holds up the card to any neighbour standing down the road at the next intersection. If the neighbour is doing the same, Rob writes down their list, but adds 1 to each number read off the other card. After a while, Rob is now telling people about the neighbours’ roads several intersections away. Of course, Rob may get the same name from two different neighbours, i.e. two routes to a road. He then crosses out the one with the larger number.

Performance

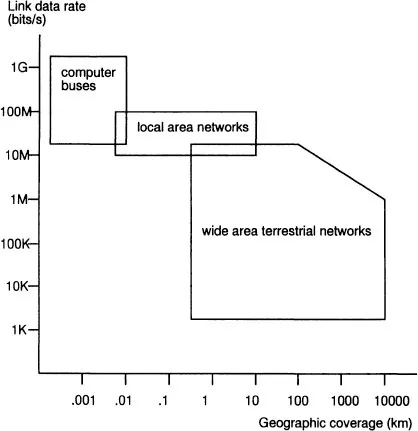

The Internet today moves packets around without due regard to any special priorities. The speed a packet goes, once it starts to be transmitted, is the speed of the wire (LAN, point-to-point link, dial up or what have you) on the next hop. We illustrate the range of communication technology speeds in Figure 1.2. However, if there are a lot of users, packets get held up inside routers (like letters in sorting offices at Christmas). Because the Internet is designed to be interactive, rather than the slow turnaround of mail (even electronic mail), routers generally do not hang on to packets for very long. Instead, they just “drop them on the floor” when things get too busy.

This then means that hosts have to deal with a network that loses packets. Hosts generally have conversations that last a little longer than a single packet – at the least, a packet in each direction, but usually several in each direction.

Figure 1.2 Range of network performance.

In fact, it is worse than that. The network can automatically decide to change the routes it is using because of a problem somewhere. Then it is possible for a new route to appear that is better. Suddenly, all packets will follow the new route. However, if there were already some packets half way along the old route, they may get there after some of the later packets (a bit like people driving to a party and some smart late driver taking a short cut and overtaking those who started earlier).

So a host has to be prepared to put up with out of order packets, as well as lost packets.

Protocols

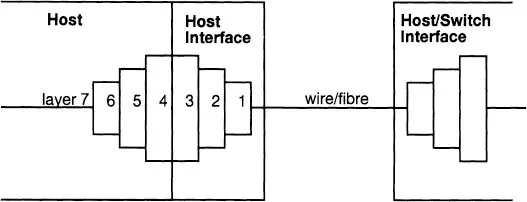

All this communication is done using standard “languages” to exchange blocks of data in packets, simply by putting “envelopes” or wrappers called “headers” around the packet. We try to illustrate how and why this is so in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Protocol “layering”.

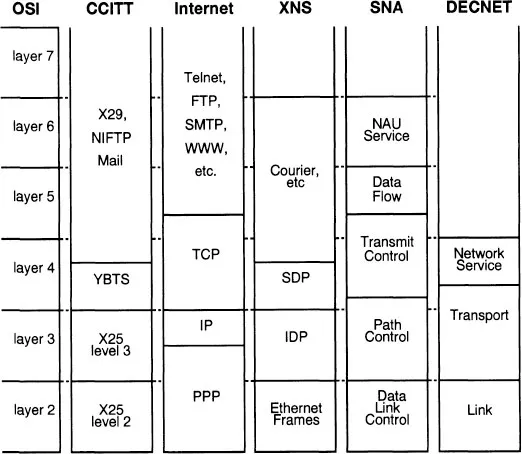

The work of routing and addressing is done by the Internet Protocol (IP) and the work of host communications by the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). TCP/IP is often used as the name for the Internet protocols, including some of the higher level information services that this book is mainly about. TCP does all the work to solve the problems of packet loss, corruption and reordering that the IP layer may have introduced through a number of end to end reliability and error recovery mechanisms. If you like, you can think of IP as a bucket brigade and TCP as drainpipe.

So if we want to send a block of data, we put a TCP header on it to protect it from wayward network events and then we put an IP header on it to get it routed to the right place. There are many different protocols in the world, and we show some of them in all their gory glory in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Comparing protocol stacks.

Host and applications

The emergence of some simple APIs (application programming interfaces) and GUIs (graphical user in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Information Highstreet – introduction

- 2 Information – are you being served?

- 3 The World Wide Web

- 4 Client programs

- 5 Serving information to the Web

- 6 Academic examples of WWW servers

- 7 Commercial Web servers

- 8 Servers galore

- 9 Problems with WWW 147

- 10 Where is WWW heading?

- Appendix A HTML grammar

- Appendix B Uniform resource locators (URLs)

- Appendix C Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

- Appendix D Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME)

- Appendix E URLs cited

- Glossary

- Index