![]()

1 Real estate, construction and economic development

Context, concepts and (inter) connections

Raymond T. Abdulai, Franklin Obeng-Odoom, Edward Ochieng and Vida Maliene

1. Background

Existing studies in the fields of real estate (RE) and construction have typically had more pragmatic concerns [see, for example, volume 29(3) of Property Management (2011)]. Such studies have also tended to approach RE and construction issues as though they were in watertight compartments. Part of the reason for this emphasis is historical. Since its beginning in the twentieth century, RE economics has traced its roots to mainstream economics and hence has tended to regard construction as necessary but not integral to its epistemology (Weimer, 1966). More recently, disciplinary subdivisions and specialisms (Malpezzi, 2009), the teaching of RE and construction courses (Boydell, 2007) and the focus of academic journals (Emerald Built Environment Newsletter, 2012) have perpetuated this schism.

The few respectable exceptions that tend to examine housing and economic development (ED), include Tibaijuka’s (2009) well-known book, Building Prosperity: Housing and Economic Development and the work of Canadian-based housing scholar Godwin Arku and his team (e.g., Harris and Arku, 2006; Arku, 2006) and a few others (Anaman and Osei-Amponsah, 2007). Within this cohort of studies, there is a strand that considers housing remittances and urban economic development (e.g., Obeng-Odoom, 2010) or housing, migration, and economic development (e.g., Firang, 2011). Another strand (see for instance, Dujardin and Goffette-Nagot, 2009) tends to focus exclusively on housing provision and its social and economic impacts. Admittedly, the Journal of International Real Estate and Construction Studies has tried to fuse together the two sub-disciplines, but it will take more time to widen the breadth of the scholarship it publishes.

These exceptions offer a substantial advance on mainstream areas in RE and construction studies, but not even these studies sufficiently address the inter-related issues of (a) the role of RE brokerage in improving the living standards of people; (b) the effect of mineral boom on construction cycles, RE and the socio-economic conditions of people in boom towns and cities; (c) corporate RE and facilities management practices and how they affect economic growth; and (d) the synergies between RE and construction and how they, in turn, affect ED.

This edited volume, therefore, attempts to fill the noted lacunae by focusing on “non-traditional” themes in emerging market economies (EMEs). The dual aim of the book is to first examine the relationships between RE and construction sectors, and secondly to explore how each sector and the relationship between the sectors affects ED in EMEs. ED in this collection refers to the sustained, concerted actions of communities and policymakers that improve the general standard of living and economic health of a specific geographical location; it is, therefore, about the quantitative and qualitative changes in an existing economy, which involves development of human capital; increasing the literacy ratio; and improvement in important infrastructure, health and safety and others areas that generally aim at increasing the general welfare of the citizenry (Todaro, 2014). The book’s emphasis is on the whole RE and construction services processes, the relationships between the sectors and how all these contribute to ED in EMEs.

The importance of concentrating on EMEs cannot be overemphasised since such nations normally receive aid and guidance from international donor community institutions such as Bretton Woods and also provide an outlet for expansion for foreign investors from the developed world.

The rest of the chapter is organised as follows. The next section gives an overview of EMEs stressing why it is a useful focus for this book. Following that section is a section that looks at the role of institutional arrangements in RE and construction markets. Section four describes the demographics and economic indicators of the case study countries whilst the last section distills and evaluates what the authors have covered in their respective chapters.

2. An overview of EMEs

EME is a term that was first used in 1981 by Antoine, an economist at the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank. As explained by Antoine, EMEs are countries that are progressing towards becoming more advanced, usually by means of rapid growth and industrialisation, and such countries experience an expanding role both in the world economy and in global politics – they tend to have lower per-capita incomes, above-average socio-political instability, higher unemployment and lower levels of business or industrial activity in comparison with the well-established economies with mature markets such as the USA, Canada, Japan and the United Kingdom. EMEs constitute approximately 80% of the global population, represent about 20% of the world’s economies and are considered to be fast-growing economies (Heakal, 2009).

Heakal (2009) has identified the following to be the main features of EMEs. First, they are characterised as transitional, which means they are in the process of moving from a closed economy to an open market economy while building accountability within the system. Thus, as an EME, the country is embarking on an economic reform program that will lead it to stronger and more responsible economic performance levels, as well as transparency and efficiency in the capital market. An EME reforms its exchange rate system because a stable local currency builds confidence in an economy, thereby reducing the desire for local investors to send their capital abroad (capital flight). EMEs normally receive aid and guidance from large donor countries and/or world organisations such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Secondly, a characteristic of an EME is an increase in both local and foreign investment. A growth in investment in a country often indicates that the country has been able to build confidence in the local economy. Also, foreign investment is a signal that the world has begun to take notice of the EME and when international capital flows are directed towards an EME, the injection of foreign currency into the local economy adds volume to the country’s stock market and long-term investment to the infrastructure. An EME provides an outlet for foreign investors or developed-economy businesses to expand by serving, for example, as a new place for a new factory or for new sources of revenue. Regarding the recipient country, employment levels rise, labour and managerial skills become more refined and a sharing and transfer of technology occurs. Thus, in the long run, the EME’s overall production levels should rise, increasing its gross domestic product and eventually lessening the gap between the emerged and emerging worlds.

Thirdly, in terms of portfolio investment and risks, because EMEs are in transition and hence not stable, they offer an opportunity to investors who are looking to add some risk to their portfolios. The possibility for some economies to fall back into a not-completely-resolved civil war or a revolution sparking a change in government could result in a return to nationalisation, expropriation and the collapse of the capital market. Since the risk of an EME investment is normally higher than an investment in a developed market, panic, speculation, and knee-jerk reactions are more common, as typified by, for example, the 1997 Asian crisis, during which international portfolio flows into these countries actually began to reverse. However, there is a direct relationship between risks and returns: the higher the risk, the higher the reward. Consequently, emerging market investments have become a standard practice among investors who wish to diversify for higher returns while adding risk. BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) are often considered the largest EMEs in the world.

Allied to EMEs is the concept of frontier market economies (FMEs). FME as an economic term was first used in 1992 by the IFC to refer to smaller EMEs experiencing or poised for strong growth. They are considered to have lower market capitalisation, less liquidity and to be less established in comparison to the larger and more mature EMEs, but still to show signs of stability and openness to investors; they can therefore best be described as up-and-coming EMEs for early-stage investors (Kuepper, n.d.; Financial Times, 2014). FMEs are thus a type of EME and, for that matter, a sub-set of EMEs. Generally, FMEs appeal to investors because they offer potential high returns with low correlation to other markets and it is expected that over time they will become more liquid and take on the characteristics of the majority of EMEs (Financial Times, 2014). Table 1.1 shows country classifications of EMEs and FMEs.

Table 1.1 Country classifications of EMEs and FMEs

Source: Dow Jones Indexes (2011); MSCI FactSet (2012), cited in Schroders (2012); Economist Intelligence (2013).

As these EMEs and FMEs currently generate the most global attention and debate, they help enhance an understanding of real estate, construction and the economy.

3. RE, construction and the economy

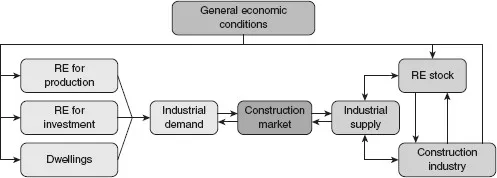

The construction and RE industries play a critical role in the economies of nations. Raftery (1991) aptly notes that the construction industry exists because people and firms need shelter or RE to carry out various activities. The construction industry supplies RE as space to three categories of clients as identified by Raftery (1991). First, individuals, public institutions and private companies who need building space as part of their production processes – production in this case covers both manufacturing and services and other non-manufacturing processes. Second, investors who demand RE space as part of their investment portfolio and therefore do not wish to use the space for the production of any particular goods and services other than supplying the building space itself. Third, individuals and families who demand housing as largely, but not entirely, a consumer commodity. Therefore in an economy the two industries are inextricably linked. This relationship is diagrammatically represented in Figure 1.1.

It is clear from the preceding discourse that construction and RE are derived demand – the demand for space for various uses leads to the demand for construction of buildings or units of RE.

Source: Adapted from Raftery (1991).

According to DiPasquale and Wheaton (1992), the analysis of RE markets presents challenges because space and asset markets are interrelated. As noted by Boshoff (2013), the earliest recording of work that distinguishes between use decisions and investment decisions with respect to RE was probably Weimer (1966), but it is Hendershott and Ling (1984) who were the first to develop a model that integrates space and capital markets into RE. Corcoran (1987) and Fisher (1992) refined the model; Fisher, for example, shows the equilibrium that exists between the short-run and long-run situations of space and capital markets. DiPasquale and Wheaton (1992) and Fisher et al. (1993) refined the model further into what commentators such as Viezer (1999) call a diagrammatic model but which according to Boshoff (2013) has been officialised in a textbook on RE economics by DiPasquale and Wheaton (1992) as the FDW-model.

The FDW-model conceptualises the interrelationships between the market for space, asset valuation, the construction sector and stock adjustment. It is a static quadrant model that traces the relationships between RE market and asset market variables as well as the adjustments that take place to establish equilibrium in the supply of and demand for RE space. Commencing with a given stock of RE space, the authors explain that changes in the macro economy (for example, increases in employment, production or the number of households; that is, market demand and supply forces) increase the demand for RE space and so, given a particular level of RE space, rents rise. This then gets translated into RE prices by the asset market. These asset prices, in turn, generate a new and higher level of construction, which eventually leads to a new and greater level of a stock of RE space.

Archer and Ling (1997) explain that generally the demand for RE space is determined by location, accessibility, level of rent and other economic factors. Regarding capital markets, Fisher et al. (1993) note that RE competes with other assets such as shares for inclusion in an investor’s portfolio. However, one benefit of RE in the case of direct RE investment is its relative low correlation with equities. This low correlation means greater diversification potential, which makes it an attractive asset class for investors who wish to optimise their multi-asset portfolio. The required rate of return (RRR) on a RE investment consists of two principal components, the risk-free rate and a risk premium that reflects the risk profile of the RE’s cash flow (Archer and Ling, 1997). The required risk premium for investments relative to their risk is determined simultaneously in the RE (specific systematic risk) and capital markets (risk-free rate) and thus the capital market (risk-free interest rate and the RE risk premium) affects the space market by altering equilibrium rents (Hendershott, 1995).

The determination of RE specific discount rates, RE values, capitalisation rates and construction feasibility occur in the RE market where in the initial stages the RE specific discount rate is determined by the interaction of the risk-free rate, market risk premium and the risk profile of the specific RE; beyond this, the market value and capitalisation rate of the RE can be assessed by discounting the expected cash flow of the specific RE, taking into consideration any government income tax effects (Archer and Ling, 1997). According to Archer and Ling, developers can assess the current RE market condition using the information on RE values and construction costs to determine the construction feasibility of a specific development. Thus, Archour-Fischer (1999) describes the FDW-model as an elegant metaphor that integrates the different markets in the built environment, with specific reference to the RE market, the capital market and construction activity.

4. Parts, chapters, and structure

This is a three-part book with 16 chapters. Fourteen of the chapters cover substantive topics, while the remaining two constitute a distillation and further analysis of the 14 chapters. Out of the 14 main chapters, 10 chapters relate to specific EMEs whilst the remaining chapters are non-country specific. Table 1.2 summarises the basic statistics of the EMEs considered in the book.

After this chapter, which provides the relevant context, the book is divided int...