- 116 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethics and Epistemology in Sextus Empircus

About this book

This book defends the consistency, plausibility, and interest of the brand of Ancient Skepticism described in the writings of Sextus Empiricus (c. 150 AD), both through detailed exegesis of the original texts, and through sustained engagement with an array of modern critics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ethics and Epistemology in Sextus Empircus by Tad Brennan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The aim of this thesis is to present an interpretation of the brand of skepticism represented in the writings of Sextus Empiricus. Currently, there is fairly broad agreement on how we should understand this form of skepticism (Sextan skepticism, as I shall call it); in the following chapters, I attempt to articulate an alternative view. The inspiration for this alternative view comes from some of Michael Frede’s writings on Sextus, but I do not know what further relation there is between his views and the views I have arrived at in the course of this project. Its most succinct description, however, might be that it is an attempt to follow out the consequences of my interpretation of his interpretation of Sextus.1

In particular, it takes as its starting point such passages as PH 11.246 and AM XI. 165, in which Sextus claims to live like other people, and to suspend judgment only about matters of abstract and technical philosophical debate.

For it is, I think, sufficient to conduct one’s life empirically and undogmatically in accordance with the rules and beliefs that are commonly accepted, suspending judgment regarding the statements derived from dogmatic subtlety and furthest removed from the usage of life.(PH II. 246)2…the Skeptic does not live according to philosophical argument (for so far as that goes we are inactive), but is able to choose some things and avoid others. (AM XI. 165)

Generally such passages as this are taken as evidence that Sextus had a very complicated stance towards practical activities and the cognitive processes involved in them. For it is taken as a given that the skeptic cannot have the full range of ordinary beliefs; and yet beliefs that are limited to how things appear to one do not seem adequate for most practical activities. So the challenge, as most interpreters see it, is to articulate a middle course between ordinary belief and mere reports of sense-data—an attenuated and weakened sort of cognitive attitude that could nevertheless underpin a life in some way described as “in accordance with” normal beliefs.

But it seemed to me worthwhile to make the experiment of supposing that the skeptic’s cognitive attitudes are really no different from ordinary beliefs at all. This heterodox supposition then brings in its train other divergences from the standard view. For changing our view about the skeptic’s beliefs naturally requires us to review other connected areas, such as suspension, ataraxia, and so on, and to make adjustments in our view of them.

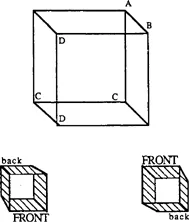

Although the alternative that I shall present differs from the standard view at a number of crucial points, it is, in another sense, nearly isomorphic to it in its overall structure. Indeed, the similarity of structure arises exactly because the disagreements are systematic;3 and this creates peculiar difficulties of exposition. The case might be compared to the familiar phenomenon of the skeletal cube, which may be visually interpreted in two coherent but incompatible ways:

The point of the comparison is this: if someone, through habit or preconception, could only readily interpret the skeletal drawing as a representation of one sort of cube, then the task of helping them to see the other possibility would not have the format of a demonstration. One could not start from some uncontroversial point, and then show that since that was so, some other things followed. For it is not the case that, in the left-hand interpretation, point A is behind point B because line CC is behind line DD. Both are true, and inter-entailing; but neither has logical priority. No more can one fully see line CC as behind line DD, before at least in part seeing point A as behind point B.

Demonstration, in the sense of establishing certain points on the basis of other, accepted points, is not really of use in this sort of case.4 What is needed, rather, is a wholesale change of perspective. Of course, the question of how, if at all, this change may be brought about in a given individual is not a question for logic, but for psychology. In the case of an essay, the question belongs to that branch of psychology called “rhetoric”; and it is my judgment as an amateur student of rhetoric that the method most likely to attain success is simply to present the alternative view, as a whole, at the very beginning of the exercise, in the hope that at least some of my readers will be able to make the shift with only that aid. Thus my second chapter contains almost no argument, and simply puts forward the outline of an interpretation.

But of course logic does have some connection to rhetoric; people are generally resistant to believing things that they concurrently believe to be incoherent. And so those who feel that the picture put forward in the first chapter is inconsistent will not accept it as an interpretation of anything. In particular, there is one sort of charge of inconsistency that I must answer if my interpretation is to receive any lasting credence, even among those favorably disposed towards it by the second chapter. Thus the third chapter will be an extended defense of the consistency of the alternative interpretation, against some very skilled and sophisticated attacks launched on it by Myles Burnyeat and Jonathan Barnes.

In the fourth and fifth chapters, I elaborate the details of my interpretation, first in regard to some of the crucial epistemological issues of Sextan skepticism, and then in regard to their ethical consequences. I shall take it that by then the main outlines of the new view have been established, and that its possibility is no longer under scrutiny. Instead, the extended examination will serve the purpose of making its finer points more familiar.

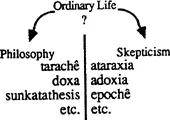

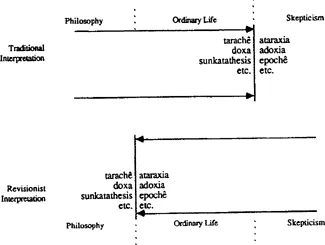

But now I should say a few more words about the sort of isomorphism I mentioned in the beginning, which suggested the cubical analogy. Both interpretations have in common a series of oppositions, between, e.g., belief and lack of belief, disturbance and lack of disturbance, assent and lack of assent, and so on. And both agree about which members of each pair go with which—e.g., both agree that belief, assent and disturbance go together, as do their contrasting privations. Because of this simple binary structure, each interpretation can be depicted by a vertical line, dividing the members of the pairs into two groups. Both interpretations also agree about which side the skeptic belongs on, and which side the professional philosopher belongs on. So much for agreement.

The disagreement between the interpretations involves a third party, peopled by those who are neither avowed skeptics nor avowed members of any other school. These are the ordinary people, or as Sextus refers to them, “those from life”.The point at issue is this: on which side of the line ought we to put the ordinary people?

Should we put them among those who have beliefs, or among those who lack them? Among those who assent, and have disturbances, or among those who do not assent and are not disturbed? Should we assimilate them, that is, to the skeptics, or to the professional philosophers? (That they must go on one side or the other is a further point of agreement between the two views).

If each of the rival views may be drawn as a pair of columns, divided by a vertical line, then the critical dispute may be envisioned synoptically by considering three columns, with philosophy and skepticism on the flanks, and life in the middle.

The interpretive contest is thus a struggle for life: on which side of Life shall we draw our dividing line? If we follow the traditional interpretation, we shall push the dividing line far to the right of ordinary life, isolating the skeptic. On this view, philosophers are really only one variety of common folk, whose beliefs are at root those of the general gender, although perhaps clarified and systematized. The skeptic, accordingly, is the odd man out; someone engaged in a very peculiar and very unordinary undertaking.

Following the interpretation that I advocate, we should push the line to the left, so as to isolate the conscious adherents of selected schools of antiquity. It is they, I shall argue, who are deeply unlike the ordinary person, while the skeptic is the one correctly allied with those from life. Or rather I should say: I shall argue that this is what Sextus means to claim. For that, in the end, is the task that I set for myself: to provide an interpretation of what Sextus Empiricus says about his own brand of skepticism and the life one leads in accordance with it.

Notes

1. I have allo found views of Sextus that are congenial to my outlook, and roughly opposed to the critical consensus, in Hallie 1985, and in the articles of Robert Fogelin, as well as in a draft of an unpublished work on Sextus that he was kind enough to let me see. For which now see Fogelin 1994.

2. All translations are based on, and sometimes merely reproduce, those of Bury 1933. I used that as a clumsy but uncontroversial touchstone, wishing to avoid the under-handed importation of tendentious interpretations via idiosyncratic translations. My thought was that if I could make my points merely with the aid of Bury’s English, then no one could accuse me of cutting my translation to suit my views. As it happened, I was pressed by David Sedley, who refereed Brennan 1994, to update and improve Bury to modern standards here and there. But I hope I have still chosen renderings that do not prejudge the important issues.

3. The phenomenon is just a consequence of the fact that any two consistent interpretations of the same set of sentences will be isomorphic.

4. Demonstration’s central role comes in establishing that a rival view is untenable because some of its parts have consequences incompatible with other parts. But in this case I am not disputing the consistency of the rival view; I concede that it may be a tenable interpretation. So in attempting to persuade its tenants to switch residence, I must show them that a more attractive view may be had from my premisses.

CHAPTER TWO

A Positive Presentation of My Interpretation

At the beginning of the dialogue that bears his name, Euthyphro is about to commit the extraordinary act of indicting his own father for murder. Euthyphro says that those who know about it are shocked by his plan, and Socrates himself is shocked. And, one might suspect, Plato has so arranged the case that his readers stand a very good chance of being shocked as well. For the victim of the alleged murder was not anyone of any importance to Euthyphro, a serf in fact, a violent drunkard, and indeed a murderer himself, on Euthyphro’s own account. Furthermore, the father’s deeds seem quite trivial, and although we must accept Euthyphro’s word that they led to the death of the serf, they do not seem to constitute murder. For the father had simply arrested the man for killing a servant while drunk, and then thrown him into a cellar or pit somewhere for safe keeping while he sent to the religious authorities to find out what to do. As it happened, advice was slow in coming, and the serf died of hunger and cold due to the father’s inattention. Even if we take Euthyphro’s word that his father was callously indifferent to the fate of the prisoner (who would likely have been killed for his crime in any case), we may feel that Euthyphro is being rather precipitous in charging him with murder—and this is apparently the opinion of Euthyphro’s contemporaries, including Socrates.

I begin with the Euthyphro, because I think it shows us some of the issues that lead the Sextan skeptic to adopt the position he has. In our lives we come to make all manner of decisions and judgments, and the grounds on which we make them, and the manner in which we make them, do not seem at all systematic or precise. Our initial judgments about Euthyphro’s rightness in prosecuting his father are affected by a strange miscellany of factors; contingencies of family relation and social class, the moral viciousness of the victim himself, the influence of drugs on his actions, the deg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: The Interpretation Presented

- Chapter Three: Its Possibility Defended

- Chapter Four: Its Epistemological Details Elaborated

- Chapter Five: Its Ethical Details Elaborated

- Bibliography

- Index