![]()

1. Introduction

If the P.E.F. is still thinking of D. Mackenzie may I say you could hardly hope to get a better man? He knows as much about scientific digging as any man alive, and is infinitely careful and trustworthy. He has a very wide reputation abroad. (Letter from David G. Hogarth to the PEF, 3 November 1909)

1.1. Duncan Mackenzie's Life and Work: A Brief Overview1

N. Momigliano

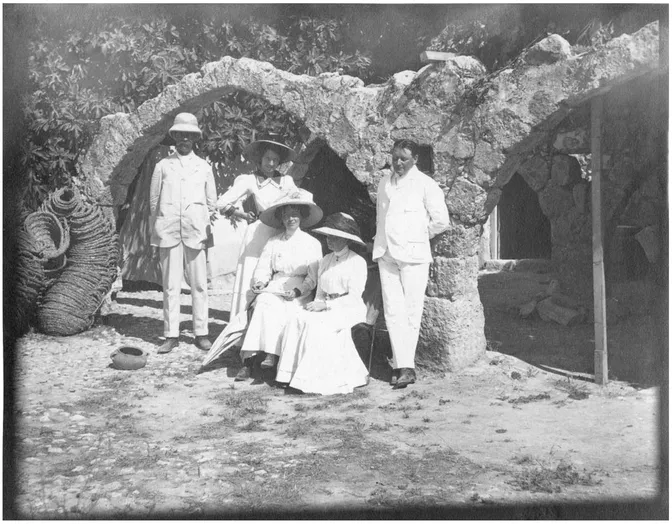

The Scottish archaeologist Duncan Mackenzie (Fig. 1.2) is best known for his work at the Bronze Age site of Phylakopi on the island of Melos (1896–99), and especially for his contribution, as Sir Arthur Evans’s field director, to the famous excavations of the Palace of Minos at Knossos, where he worked from the spring of 1900 until 1929, with some interruptions. Between 1910 and 1912, he was engaged as PEF ‘Explorer’, and directed excavations at Beth Shemesh (Figs 1.1, 1.3 and 1.4); in 1913 he worked for the Wellcome expedition to the Sudan, before returning to his Knossian work until his retirement.

Unlike many of his predecessors and contemporaries, men of independent means with a keen interest in archaeology, such as Heinrich Schliemann, Augustus Henry Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers and even Sir Arthur Evans, Mackenzie earned his living through digging, and was therefore one of the very first and very few professional field archaeologists at a time when archaeology was beginning to develop as an independent discipline. He was a first-rate excavator, totally devoted to his work, and a man capable of great personal loyalty and generosity. But he could also be oversensitive, difficult to pin down to rules and dates, impractical and unbusinesslike about money matters. In addition, he was not a particularly gifted or prolific writer. These weaknesses in his character and work habits often led to clashes with his employers, and especially with the PEF.

Mackenzie was born in 1861, in the Highlands of Scotland, in a poor family living in the small crofting village of Aultgowrie (Ross-shire), which is located about 15 miles from the town of Inverness. He was the fourth of nine children born to Alexander Mackenzie, a gamekeeper. After attending a local school in the nearby village of Marybank and a secondary school in Inverness, in 1882 he enrolled as a student of the Arts Faculty at the University of Edinburgh, where he graduated with an MA in philosophy in 1890. Subsequently, he studied philosophy and classical archaeology at the universities of Munich, Berlin and Vienna. In 1895 he received his doctorate from Vienna, after writing a dissertation on the heroon of Gölbaşı (ancient Trysa) in Lycia, under the supervision of the eminent archaeologist Otto Benndorf.

After completing his doctorate, in December 1895 Mackenzie became a student of the British School at Athens, and in the spring of the following year he took part in the school’s excavations of a site south of the Olympieion and near the Ilissos river, which some have identified with ancient Kynosarges. It is possible that at this time Mackenzie made the acquaintance with Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who had worked with Schliemann at Troy and Tiryns, and was then the director of the German Institute in Athens and had shown an interest in the Kynosarges excavations. Most importantly, in the summer of 1896 Mackenzie started his connection with the British School’s excavations on the island of Melos, especially at the important Bronze Age site of Phylakopi. His contribution here was crucial, as duly acknowledged by Cecil Smith and David Hogarth, who were the directors of the British School at Athens during this period (Hogarth succeeding Smith in 1897), and as recognized also by archaeologists who later worked at this site, such as Colin Renfrew. At Phylakopi, between 1896 and 1899, Mackenzie effectively acted as field director, and was the only archaeologist who was present throughout the dig. In addition, he kept an important excavation record. Mackenzie’s Phylakopi excavation daybooks, like those he later kept at Knossos, Beth Shemesh and in the Sudan, are mines of unpublished information; they also show a precision in the recording and an attention to problems of methodology and interpretation which are remarkable for the period. Suffice here to observe that, in 1963, Renfrew produced an unpublished transcription of Mackenzie’s Phylakopi daybooks, and in his introduction remarked that they

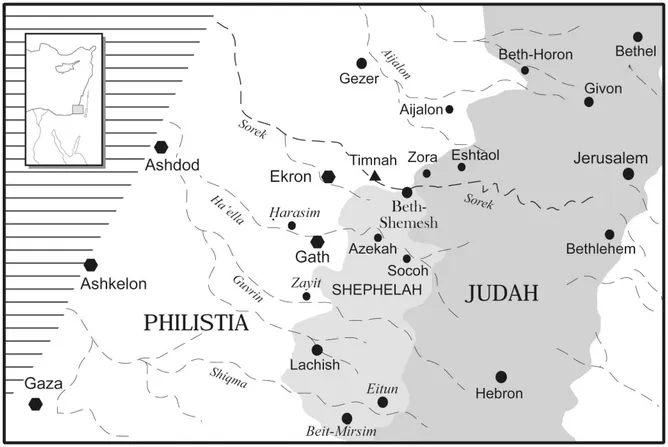

FIGURE 1.1. Map showing location of Beth Shemesh.

are outstanding examples of systematic archaeological reasoning, produced at a time when scientific principles of excavation had not yet been established. Duncan Mackenzie was one of the very first scientific workers in the Aegean, and his Daybooks have therefore a considerable historical value.2

The same applies to the daybooks he kept while working on his subsequent excavations. As mentioned above, Mackenzie was not a very prolific or gifted writer. He did publish a few seminal papers, such as his chapter on the ‘successive settlements’ or ‘cities’ of Phylakopi (perhaps modelled on Dörpfeld’s Trojan ‘cities’), or the articles he wrote on the Minoan pottery of Knossos, in addition, of course, to his valuable volumes on Beth Shemesh. But his various excavation daybooks are arguably his greatest contribution to archaeology. These daybooks, quoted extensively and sometimes without acknowledgement, formed the basis for important publications by others. Although some of Mackenzie’s own conclusions and interpretations concerning the various sites that he excavated have been challenged by subsequent scholars, these challenges have largely been made possible by the detail and precision of his own records — and this is, in itself, further testimony to their usefulness and importance.3

FIGURE 1.2. Duncan Mackenzie at Beth Shemesh (1911), far left, wearing pith-helmet, with visitors (Dr Masterman, Miss Douse, Miss Dickinson and Fraulein Beck) (PEF/P/MACK59).

After Phylakopi, in the early months of 1900 Mackenzie moved to Rome, with his sister Christina, and the Italian capital became his home for the next decade, whenever he was not engaged in fieldwork. In mid-March 1900, on the advice of Hogarth, Evans sent Mackenzie a telegram, offering him the job of superintending the planned excavations at Knossos. Mackenzie replied immediately, and on 23 March 1900 he started the first of his many daybooks recording the excavations of this most famous site.

From 1900 until 1910, Evans and Mackenzie excavated at Knossos every spring, with the exception of 1906, a year in which no archaeological work took place for lack of funds, and also because Evans, unsatisfied with the accommodation available near Knossos, was involved in the completion of his Villa Ariadne, which subsequently became his Knossian home and excavation headquarters. During this decade, Mackenzie usually spent three or four months on Crete every year and, in addition to his work for Evans, in the mid-1900s he travelled widely in Europe, the Mediterranean and the Near East, thanks to a Carnegie Fellowship in History. Furthermore, he conducted archaeological explorations in Sardinia, in collaboration with the then director of the British School in Rome, Thomas Ashby, and the architect Francis G. Newton, focusing on nuraghi and other megalithic structures, as attested by some of his publications (see bibliography of Mackenzie, below).

FIGURE 1.3. Beth Shemesh looking south-east (Photo courtesy of Albatross Aerial Photography Ltd).

After a decade of work at Knossos, Evans began thinking about a pause in the excavations, so that he could embark on a large monograph presenting his spectacular discoveries. It is likely that he intended to involve Mackenzie in this work, but Mackenzie’s collaboration with Evans and his Sardinian explorations were interrupted by his unexpected appointment by the PEF.

In 1909, R. A. S. Macalister resigned from his post of PEF ‘Explorer’, which he had held since 1901, with responsibility for the excavations at Gezer, to take up a Chair in Celtic Archaeology and Early Irish History at University College Dublin. Thus, Mackenzie was appointed as Macalister’s successor at the beginning of December 1909, at the suggestion of Archibald Dickie (the PEF’s Assistant Secretary at that time), who had met him in Athens in 1896.

The principal objective of his appointment was the excavation of cAin Shems, a site that is located in the Sorek valley, about 20 miles west of Jerusalem,

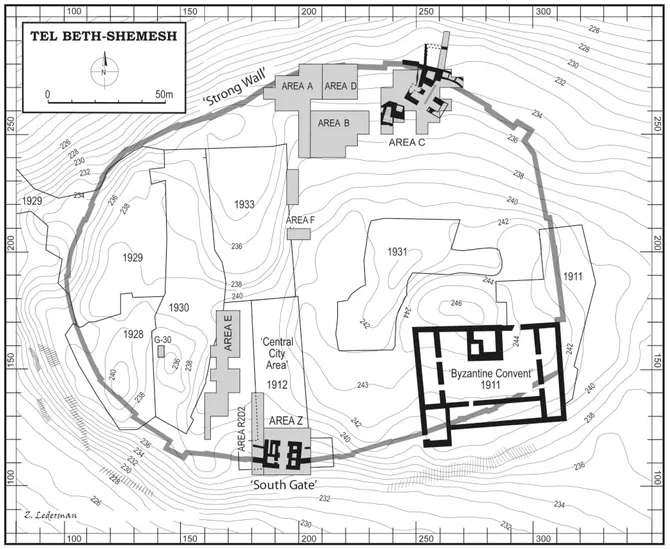

FIGURE 1.4. Beth Shemesh: map of excavation areas, 1911–2012.

where the Sorek stream (Wadi es-Surar) emerges from the hills of Judah, at the crossroads of Canaanite, Philistine and Israelite cultures (Fig. 1.1). cAin Shems had been chosen for exploration by the PEF at Macalister’s suggestion, because of its identification with the biblical Beth Shemesh and the expectation that it would throw some light on the question of the origins of the Philistine culture, which some scholars had connected with the Aegean. Mackenzie had previously travelled in Turkey, Egypt and Palestine (including a visit to Macalister at Gezer), but was not an expert in Near Eastern or biblical archaeology, nor did he know Arabic. His exceptional reputation and experience as an excavator as well as his gift for languages, however, were considered sufficient qualifications to justify his appointment. In addition, it was believed that his great knowledge of Aegean archaeology, and pottery in particular, would come in useful with regard to the Philistine question, a belief that was largely fulfilled, since Mackenzie was the first archaeologist to establish the stratigraphical and chronological context of Philistine pottery, partly due to his understanding of the Aegean ceramic sequence.

Thus, in March 1910 Mackenzie travelled to Jerusalem but, for a variety of reasons, did not start excavations at Beth Shemesh until the spring of 1911, much to the dissatisfaction of his new employers. The causes of this considerable delay can be found in the complexities involved in obtaining first a firman (permit) and, second, a suitable commissaire, that is, the representative of the Ottoman authorities on the excavations.

An excavation permit was eventually granted in June 1910, but by then Mackenzie was back in Crete to complete his obligations to Knossos. He returned to Jerusalem in mid-July to start excavations at cAin Shems, but the appointment of the commissaire proved to be very problematic. Unfortunately, instead of waiting patiently in Jerusalem for a solution and paying attention to bureaucratic niceties, Mackenzie and his colleague Francis G. Newton (who had been appointed as architect of the PEF excavations) in September 1910 decided to go on an expedition to the land of Moab. This was supposed to be a short excursion, but lasted over two months, went as far as Petra and included a visit to Damascus on the return journey. By the time Mackenzie and Newton returned to Jerusalem, the rainy season had arrived (preventing the start of excavations for several months), the permit that had originally been granted in June had elapsed (because no excavations had started within the prescribed time) and, last but not least, Mackenzie had left for Moab without informing the Director of Antiquity, Halil Bey, causing great offence. All this led to considerable friction between Mackenzie and members of the PEF committee, who were also beginning to be rather dissatisfied with his lack of regular written reports and financial accounts.

Eventually, a new permit was issued and a suitable commissaire was appointed. The first campaign of exc...