- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written from the perspective of developing countries, this book discusses the development process from a spatial perspective, focussing particularly on the evoltuion of the intra-national space-economy. With emphasis on African nations, this book offers a distinctive interpretation of the current situation and policy prescriptions differing significantly from previous literature in the area.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

The second half of the twentieth century has been characterized in its opening years by the retreat of colonialism all over the world. Within a space of twenty years between 1945 and 1965, some fifty-seven countries, mainly in Africa and Asia, became politically independent. During the same period, the convention was established that as each country became politically independent it sought and was accorded membership of the United Nations. Thus, the size of the membership of the United Nations came to represent roughly the number of independent political entities in the world. Between 1945 when the organization was established by charter and 1965, membership rose from 51 to 118 nations. By 1971, the number had further risen to 132. Today, membership of the United Nations stands at 142 which is just sixteen short of the total number of territorial entities which presently cover the whole earth surface, apart from the sixty-five dependencies of various European powers which mostly comprise small islands, continental enclaves or portions of the desolate Antarctic continent.

With the issue of overt colonialism largely resolved, the most important global preoccupation, particularly of the last three decades, has been the question of the relatively poor living standards and the degrading quality of life of the vast majority of the population of the world. A close relationship was observed between relative poverty and the status of being an erstwhile colony. This relationship was noticed not only in respect of the newly independent countries of Africa and Asia, but also those countries of Central and South America which became politically independent as far back as the first quarter of the nineteenth century. All of these countries came to be regarded as underdeveloped and their problems of absolute and relative poverty became an overriding international concern. Indeed, at no time in human history has so much intellectual energy and humanitarian concern been directed towards understanding the basis for such poverty and evolving strategies for its eradication.

Not unexpectedly, therefore, the academic community, particularly in the rich and more developed countries of the world, accepted the challenge of this unprecedented situation. Its members sought, on the basis of their understanding of past conditions in their own countries and the prevailing circumstances in the underdeveloped territories, to erect theoretical frameworks and operational models of how the poverty situation could be transformed. The discipline of economics came to dominate the intellectual effort in this direction and tried heroically to adapt the tools of analysis which were developed for the management of the complex economies of the rich countries, to the needs of the underdeveloped ones.

The United Nations took the leadership in focusing world attention on the extent of global poverty and in monitoring changes in the situation through continuous and comprehensive data collection. To give visibility to its effort and to rally all countries of the world to co-operate in tackling this problem, the United Nations declared the 1960s its First Development Decade. The 1970s were in turn declared the Second Development Decade and it was hoped that the unimpressive performance of most of the underdeveloped countries of the world during the first decade would be improved upon in the second. In the closing years of the Second Development Decade the story remains far from inspiring. In many countries, although a minority of the population seems to have prospered almost beyond belief, the miserable conditions in which the majority lives seem to have persisted and in many cases to have worsened.

This negative product resulting from deliberate intervention by governments on the basis of well considered, theoretical prescriptions has led to much soul searching within the academic community. As the present decade has progressed, the volume of literature re-examining the premises and theoretical underpinning of attempts at development in the poor countries of the world has increased. Besides economics, other disciplines in the social sciences, whose possible contributions have not received much attention in the past, now find greater receptivity to their points of view and to the alternative perspectives on the problems of development which they provide.

One of these disciplines is geography with its traditional concern with regions and spatial organization. Initially, the geographical interest in development was conditioned by its regional preoccupation and much of its theoretical contribution was to the emerging field of urban and regional planning.1* Indeed, as long as the subject shied away from confronting the problems of development in their totality, its conceptual contribution came to be limited largely to seeking ways and means of correcting at the urban and regional levels distortions arising from decisions taken at the national level. In the last ten years it has become increasingly obvious that such attempts at correction were either impractical or counter-productive, since they tend to worsen existing distortions. Concepts such as those of growth centre strategies of regional development came to be seen as attempts at, as it were, pouring new wine into old wineskins with all the consequential disastrous effects this entails.

In these circumstances an alternative viewpoint has been evolving within geography which sees development as an attempt by organized human communities to define new spatial relationships among their members and between them and their environment. This viewpoint takes the nation state as its unit of interest, in terms of both its internal social relationships and its external relations with other states. Thus, while it is conscious of regional inequalities in countries at different levels of development, it is even more mindful of the ever widening gap in the opportunities for meaningful human existence between advanced industrial countries and those referred to as underdeveloped.2

The extension of the spatial perspective to problems of underdevelopment is a very recent event. Yet it is already yielding insights into the process of development which need to be given greater attention than hitherto. In the present volume, although this perspective has been largely generalized, some attention has been paid to the variety of forms and levels of spatial organization found among the underdeveloped countries. The existence of such variety must not, however, be allowed to blur the appreciation of the real essence of the problem of underdevelopment. The need constantly to distinguish between the essential character and the differing surface manifestations of underdevelopment is one which remains paramount throughout this book.

The heterogeneity of underdeveloped countries

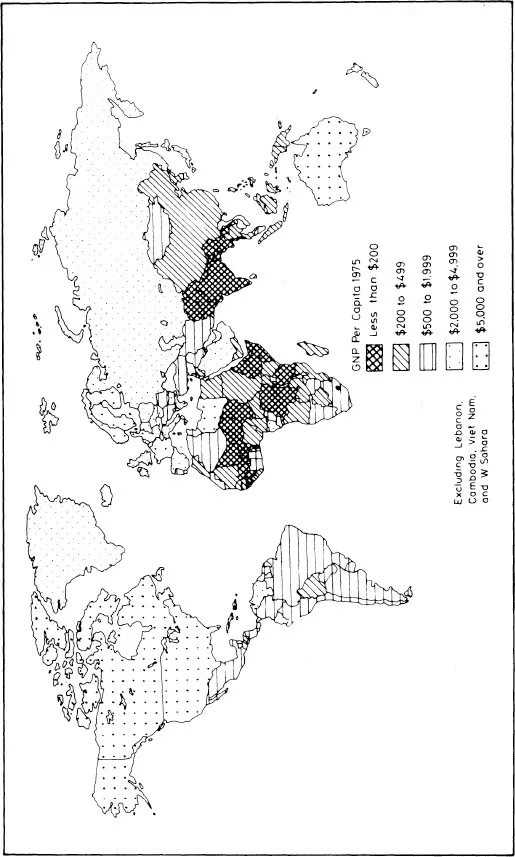

As of 1975, some 108 countries (excluding China) were regarded, according to Abdalla,3 as constituting the Third World (see Figure 1). The term ‘Third World’ is often used as synonymous with underdeveloped countries and together these countries accounted for some 1958 million people or 63 per cent of world population, excluding China. The most significant fact about all of these countries is their integration into a global economy where their major role has been that of producers of industrial raw materials. This integration has been largely the product of an industrial revolution which began in England in the eighteenth century and had become well established in Western Europe and North America by the second half of the nineteenth century.4 This revolution brought about an international division of labour whereby the countries of Western Europe and North America came to concentrate on production and activities which benefited most from technological progress, as well as from the fuller and more rational utilization of the abundant resources of labour and land found particularly in other areas of the world. The increased overall global activity was accompanied by the accentuation of interdependence among all the countries of the world. Within the framework of this interdependence, two patterns of development emerged. The first was in those countries of early industrialization whose economies came to be based on technological progress and a rapid accumulation of capital. These countries constituted the core or centre from where the volume and trend in global economic activities came to be determined and directed. Their development entailed increasingly complicated production processes which constantly required not only a change in the relative quantities of production factors, particularly an increasing amount of capital per unit of labour, but also a qualitative transformation of these factors through a progressive improvement in the characteristics of human labour.

Figure 1 The distribution of underdeveloped countries

The second emerging pattern of development took place in countries peripheral to the central industrial region in response to changes in overall demand emanating from and usually effected through agencies based in the core. This second type of development was characterized by its essential dependence on circumstances at the centre. In general, it gave rise to economies which were always extensive in character and whose productivity could be increased without significant changes in the focus or mode of production. Thus, the replacement of a subsistence crop such as yam by an export crop such as cocoa brought about an increase in overall output but required no major changes in production organization or techniques. In other instances, such as mining, this peripheral development took the form of assimilating modern techniques and intensifying the input of capital in a production sector which lacked the capacity to transmit its growth to the economy as a whole and was strictly geared to export. In either case, peripheral development had little capacity to transform traditional techniques and organization of production. Nevertheless, by requiring the modernization of infrastructures and some part of the state apparatus, this type of development set in motion an historical process which opened up important new possibilities in countries of the periphery.

The peripheral and dependent nature of their economies is perhaps the single most important factor influencing conditions and events in underdeveloped countries today. However, among themselves, these countries are so heterogeneous that the surface manifestations of these influences give the appearance of tremendous variation. The heterogeneity of underdeveloped countries can be examined under three broad headings: population, natural resources and current levels of development.

Population

With regard to population, the most significant factor differentiating underdeveloped countries from one another is to what extent their peoples are indigenous. In virtually all the countries, the initiation of the current pattern of dependent development followed from the migration of substantial numbers of people from the central industrial countries. In the countries of Africa and Asia, the size of this foreign population was never considerable and the prospect of their complete assimilation into the local population was limited. Even where, as in southern Africa, they formed a settler community, they remained a distinct minority whose survival within the country was based on the exercise of brute force. By contrast, in Central and South America, the immigrant groups came to dominate the local population so thoroughly that the latter became the minority struggling to preserve its cultural identity. In development terms, the significance of this distinction has been, at least until recently, a greater ease of penetration of the countries of Central and South America by forces from the central industrial region. Such penetration, either by individuals or enterprises, does not present serious problems of racial and cultural differences such as are noticeable in the case of Asia and Africa. In consequence, one notices a higher level of foreign investment and development in this group of countries.

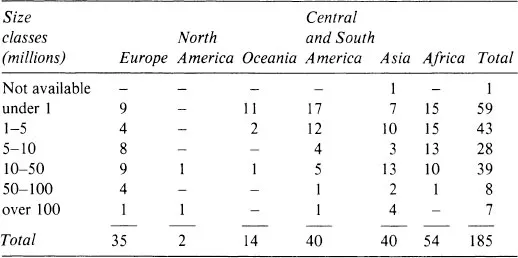

Another important feature of differentiation is the size of the countries. Underdeveloped countries show tremendous variation in size due to the intense struggle for colonies among the countries of the centre during the nineteenth century. As a result, the three continents of Africa, Asia and Central and South America have between them 134 out of the 185 national units (or 73 per cent) making up the world. As Table 1 shows, however, most of these nation states have fewer than five million people. Seventy-six out of 102 of such countries are to be found in the underdeveloped regions of Africa, Asia, Central and South America. At the same time, the Third World has countries such as India with over 600 million, Indonesia with 132 million, Brazil with 107 million and Nigeria with 75 million. This wide variation in population greatly affects the capacity for independent action by many of these countries as they attempt to become more self-reliant in the course of their development.

Table 1 Size distribution of countries, 1975

Source: World Bank Atlas (1977)

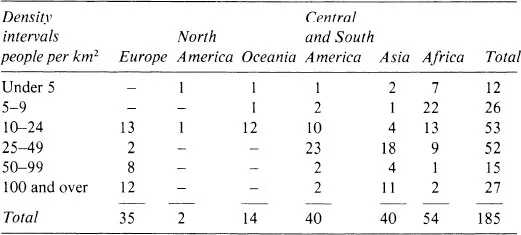

Table 2 Density distribution of countries, 1975

Source: World Bank Atlas (1977)

The density of population is also a major factor of differentiation. Most African countries have densities of less than twenty-five persons per square kilometre, with only the two small countries of Burundi and Ruanda having densities of over 100. By contrast, most countries of Asia have densities of over twenty-five persons per square kilometre and more than a quarter of them have more than 100 persons per square kilometre. Central and South American countries are intermediate between the two with most of the mainland countries having densities of between ten and twenty-four persons while the islands have between twenty-five and forty-nine persons. Again, the fact of density is significant since it provides a crude index of available land resources for future development. This index, it must be emphasized, is particularly crude, since in most of the countries actual cultivable land is limited and density per unit area of cultivated land is considerably higher than depicted.

Natural resources

The heterogeneity of underdeveloped countries is further compounded by variations in their natural resource endowments, especially as viewed from the perspective of the central industrial countries. This perspective is crucial to the extent that it has determined the position of each of the countries within the system of the international division of labour. On this basis, underdeveloped countries fall into three broad groups. The first are the temperate countries of South America whose climatic and vegetal resources made them eminently suitable for the production of those agricultural commodities, notably beef, requiring an extensive use of land. Countries such as Argentina and Uruguay became part of the expanding frontier of the industrializing European economy to which European agricultural techniques were transplanted at an early stage. The very extensiveness of the agriculture practised and the sheer volume of freight involved, necessitated the creation of a widespread transportation network in these countries which indirectly led to the rapid unification of their domestic market, focusing on the major ports of shipment.

The second group comprise countries in the tropical zone whose agricultural exports were needed mainly as industrial raw material. Most of the underdeveloped countries of Asia, Africa and parts of Latin America fall into this category, their role being to supply the central regions with such commodities as sugar, tobacco, coffee, tea, cocoa, groundnuts, palm produce, cotton, rubber, sisal and timber. The rapid expansion of demand for these commodities in countries of the centre during the second half of the nineteenth century was an important factor in their colonization during this period and resulted in the integration of the economies of the tropical underdeveloped countries into the world market system. None the less, tropical commodities were of limited significance as a factor in the development of countries of the centre, although they involved the opening up of large areas for settlement. Consequently, tropical countries did not attract much capital for the creation of a complex infrastructure and production was not infrequently allowed to continue within the framework of traditional organization and techniques.

The third group of c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- Part One: Orientation

- Part Two: Rural Development

- Part Three: Urban Development

- Part Four: National Integration

- Notes and references

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Development Process by Akin Mabogunje in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.