- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, originally published in 1988, examines the Highlands and Islands of Scotland over several centuries and charts their cultural transformation from a separate region into one where the processes of anglicisation have largely succeeded. It analyses the many aspects of change including the policies of successive governments, the decline of the Gaelic language, the depressing of much of the population into peasantry and the clearances.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gaelic Scotland by Charles W J Withers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS AS CULTURE REGION

The Highlands is a very general name for a large tract of the Kingdom, which appears to be best defined by the boundary of the Gaelic language.1

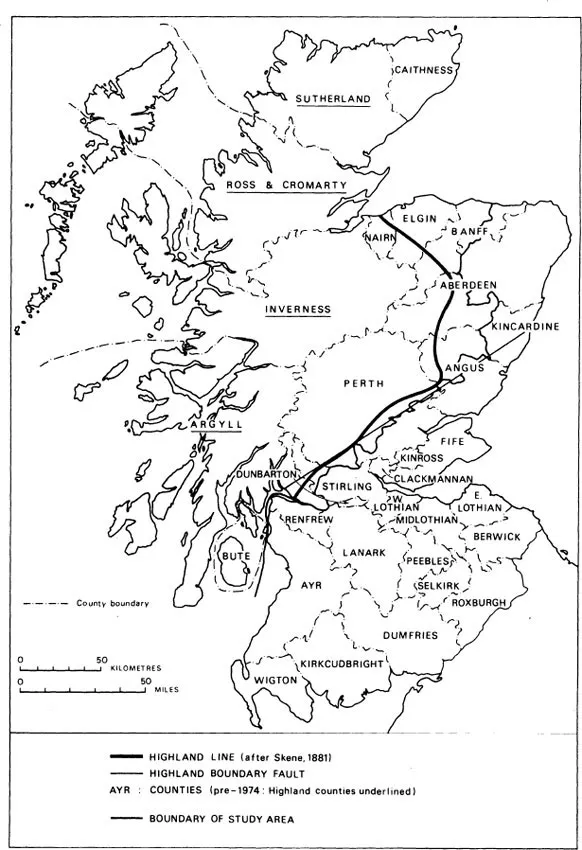

The Highlands of Scotland, together with the outlying western islands, present a region both distinct from the Lowlands and itself characterised by areas of individuality. Geologically, the Highlands are divided from the Lowlands by the Highland Boundary Fault which runs from Stonehaven on the east coast to Helensburgh on the west and divides the Precambrian rocks of the west and north from the younger Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks of the Midland Valley to the south and east.2 To the geographer, this upland massif to the north and west is separated from the Lowlands by the ‘Highland line’ and represented as the ‘Highland counties’ – Argyll, Ross and Cromarty, Sutherland, Inverness – together with parts of northern Perthshire and western Caithness (Figure 1.1). The Highlands region as a whole is seen as one whose climate is cool and wet, whose underlying geology has determined a scanty soil cover and where the incised lochs and mountainous terrain have made communication difficult, human settlement limited, and cultivation of the land an uncertain affair. Compared to the rest of Scotland, the Highlands are ill-provided with natural resources such as coal and iron. The relief, with much of the area over 250m, has limited land use largely to rough pasture and forestry.3 Population is today thinly scattered, concentrating in several towns along the coastal margins. Even in the past when numbers and distribution were different from today, Highland Scotland was never as densely populated as the Lowlands, although shifts in balance between population and resources in the rural Highlands occasioned levels of poverty and hardship more widespread and severe there than in the Lowlands.

Whilst the Highlands and Islands may be considered distinct in a number of ways from Lowland Scotland, the region should neither be seen as uniform in its characteristics nor wholly separate. Not all to the north of the ‘Highland Line’ is typically Highland: the soils are not everywhere thin and unproductive nor the land everywhere dissected by narrow lochs and high ranges. The division between Highlands and Lowlands is not a simple division between north and south but much more one between the ‘farming Highlands’ to the south and east and the ‘crofting Highlands’ to the north and west. The soils of coastal eastern Ross and Cromarty and parts of eastern Sutherland, for example, are closer in type and productive capacity to those of the Lowlands than to soils in the upland west of those counties. The narrow coastal strip around Inverness, in the northern parishes of Moray, Nairn and the eastern upland areas of Aberdeen, has a richness of landscape now and an agrarian economy in the past more Lowland than Highland in nature. Discussion of the geography of Highland Scotland must needs recognise this diversity within unity; in the way people drew a living from the land, in the balance between population and resources, and in the connections different parts of the Highlands had with outside influences.

Figure 1.1 Scotland and the Highland Line

In the past the Highlands as a whole, both the hill country proper and the coastal plains, have been considered as the area within which the Gaelic language was spoken or the clan was the predominant social system. Definition of the Highlands by language, the Gaelic-speaking culture area or Gaidhealtachd is particularly important. But although it is common today to separate Highlands from Lowlands on the basis of agrarian economy, geology or even topography and climate, and, for the geography of the past more proper to distinguish between the two areas on the basis of social system and language, the terms ‘Highlands’ and ‘Lowlands’ describing two cultural provinces within Scotland have not always been in existence. Neither the terms themselves nor the division within Scottish culture and geography they denote had any meaning before the end of the fourteenth century.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE HIGHLANDS

Several reasons may be advanced to explain the social and geographical emergence of the Highlands as a distinct region within Scotland by the late 1300s. Firstly, those changes in society and on the land attendance upon the extension of feudalism in medieval Scotland were felt less in those parts north of the Forth and Clyde than in the Lothians or the Scottish borders. In the upland north and west, such changes – the expansion of burgh economies, the role of justiciars, baronies and other feudal controls on land and society – were hardly felt. Secondly, the simple fact of distance and the remoteness from authority allowed the population in the Highlands to exist largely unaffected by events in the south. In addition the Gaelic language underwent a major decline in social and political status during the medieval period. In the eleventh century, Gaelic, known as the Scottish language by virtue of its political prestige and nationalist associations was predominant throughout Scotland and in use, to varying degrees, from the Tweed to the Pentland Firth. But by the late fourteenth century Gaelic had retreated into its Highland habitat and had lost its connotations as the Scottish language.4 At the same time as it was retreating from the Lowlands, Gaelic, was being replaced by English as the language of civility and status. As a result of its rise up the social scale and the connotations of Gaelic with geographical and social inferiority, the English language in use throughout Lowland Scotland became known as ‘Scottis’ or Scots; Gaelic, in losing its nationalist and political associations, became known as ‘Irish’ or ‘Erse’ in reference to its Irish origins. This paralleled the emergence of the Highlands-Lowlands division in the then Scottish consciousness. The result of these changes was, by about 1400, the appearance of a dualism in Scotland’s geography between the Gaelic Highlands and the Scots or English-speaking Lowlands. The Highland-Lowland boundary line is thus a construction from a particular period in Scottish history. The terms ‘Highlands’ and ‘Lowlands’ have no place in the historical sources surviving from the period before about 1300: ‘they had simply not entered the minds of men’.5

This division is, to one author, apparent throughout Scotland’s literary history: ‘as far back as the literature of Scotland goes, the Lowlanders regarded the Highlanders with the feelings of contempt and dislike which the representative of a higher form of civilisation (as he conceives it to be) cherishes toward the representative of a lower’.6 But it is a distinction that would not have been articulated before the 1400s, and is not one shared exactly by the Gaelic historical and literary tradition. MacInnes notes, ‘although Gaels recognise more or less the same division of the country into Highland and Lowland, there are certain subtle differences in that division we are perhaps prone to ignore … Gaidhealtachd and Galltachd (the Lowlands) are abstract terms, not ordinary placenames, and the areas they designate are not drawn with precise boundaries’.7 Several Gaelic tradition-bearers and poets extend the idea of the Gaidhealtachd beyond the Highland line, to encompass those areas of Scotland once Gaelic but now Lowland, and to claim for Gaelic an historical heritage greater in the past and lost through outside agency. Alexander MacDonald, the eighteenth-century Gaelic poet, writing of the ‘Miorun mor nan Gall’ – the ‘great ill-will of the Lowlanders’ – pointed to the need to re-affirm Gaelic literary tradition as the bearer of a more truly Scottish culture. Assessment of literary evidence must, of course, bear in mind the selectivity of the writer and the historical context of the work, but it is nonetheless true that such evidence ‘from within’ – Gaelic poetry and historical tradition, native expressions of sentiment or protest – has been too often ignored by geographers and historians of Highland Scotland. As MacInnes further notes, Gaelic tradition has regarded the Highland Line not as a fixed border line between two cultures but as reflection of the earlier decline of a greater Gaelic Scotland. But to the Lowlander, when that region now known as the Highlands entered history and literature, Gaelic cultural forms and value systems no longer carried with them any sense of a lost Scottishness or even of contemporary status. Gaelic had become the language, and, in wider terms the symbol of a geographical region whose cultural forms and social order were anathema to the standards of civilised,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 INTRODUCTION: THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS AS CULTURE REGION

- 2 CIVILISATION AND THE MOVE TO IMPROVEMENT

- 3 ANGLICISATION AND THE IDEOLOGY OF TRANSFORMATION 1609–1872

- 4 POPULATION GROWTH AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF HIGHLAND AGRICULTURE 1650–1891

- 5 INDUSTRIOUSNESS AND THE FAILURE OF INDUSTRY

- 6 THE GAELIC REACTION TO CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION

- 7 CONCLUSION: THE TRANSFORMATION OF A CULTURAL REGION

- Bibliography

- Index