![]()

Part I

Genesis, historical ties and contemporary relations

![]()

1 The ‘birth’ of Brunei

Early polities of the northwest coast of Borneo and the origins of Brunei, tenth to mid-fourteenth centuries

Stephen Charles Druce

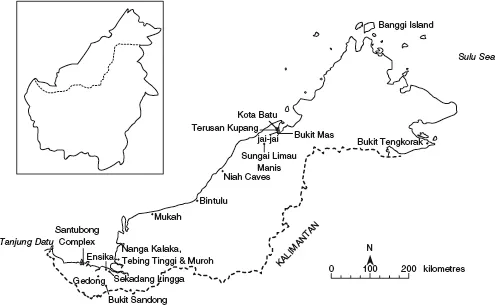

This chapter explores the appearance of early polities and development of complex societies between the tenth and mid-fourteenth centuries along the northwest coast of Borneo, a region encompassing present-day Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah. Archaeological data from this region provides evidence for the existence of a number of coastal or semi-coastal complex societies in the first decade of the second millennium CE on the northwest coast, with the most significant in Brunei and the Limbang, Santubong and Gedong areas of Sarawak. The development of these early polities in this northwest region as well as in the island as a whole remains obscure, and it is fair to surmise that we know more about the prehistory of Borneo than its proto-historical period.1

Several writers have argued that two of the polities that arose along the northwest coast were established by peoples from outside Borneo.2 The focus, then, of this chapter is to examine this possibility within a broad historical and archaeological framework, working on the premise that there are three possibilities for the origin of the said polities. The first possibility is that the polities emerged as a consequence of a gradual development in complexity among indigenous groups located in riverine regions, stimulated by the advent of regular and sustained external trade and the introduction of elite imported goods in exchange for local forest and sea produce. The second is the likelihood that Malay-speaking trading groups from polities in the western part of the Malay Archipelago established trading polities based on political systems similar to theirs, and thereafter developed riverine trading networks with inland indigenous groups, presumably to obtain forest produce for the international market.3 The third possibility is a combination of the first and second, where external Malay-speaking trading groups settled in, or close to, existing indigenous polities that subsequently became the dominant political and cultural force.

Support for advancing these possibilities is drawn from archaeological and linguistic data, recorded oral traditions and indigenous written sources, and information found in Chinese records. This investigation opens with an overview of data relating to before the tenth century, including the problematic associations that some of the source materials have made between the northwest coast of Borneo and early toponyms mentioned in Chinese sources.

The paucity of evidence for pre-tenth-century developments

The earliest evidence of external trade along the northwest coast of Borneo comes from Bukit Tengkorak in northern Sabah, where Bellwood and Koon found evidence of trade in obsidian between early Austronesian settlers of this region and the Bismarck Archipelago dating to about 3,000 years ago.4 Fragments of an approximately 2,000-year old Dong Son drum have also been found in Banggi Island, which lies off the north coast of Sabah – presumably the only such example known in northwest Borneo.5 For the first millennium CE, there is little evidence in northwest Borneo of any external trade or development in political complexity vis-à-vis Java and Sumatra. The region appears to have been marginal. There is evidence, however, of significant Indic influence in the early first millennium, but this is uncovered in the island’s southeast at Kutai, where stood seven stone pillars (yūpa, sacrificial posts) inscribed with the early Pallava script and Sanskrit language that date to about the early or mid-fourth century CE.6 One of the inscriptions, inscribed during the reign of King Mūlawarman (referred to as the ‘lord of kings’) lists the names of three generations of kings. Another ruler called Aśwawarman is attributed as ‘the founder of the dynasty’. The Kutai inscriptions appear to have been written within the context of ‘state formation’ and illustrate the earliest evidence for the development of a complex polity in Borneo, however short-lived, that used Indic Hindu concepts.

Very different and unrelated Sanskrit inscriptions, dated a century or more later than those of Kutai, have been found in West Kalimantan, near the Kapaus river at Batu Pahat, and in Brunei and Limbang. The Batu Pahat inscription, the most extensive of the three, is on a massive boulder that is inscribed with seven stupas and eight Buddhist inscriptions that relate to rebirth and karma.7 Two brief Buddhist inscriptions written in Sanskrit script and language have also been found in Brunei. Although the context is somewhat different to that of Batu Pahat, they too relate to karma and rebirth. One of the brief Brunei inscriptions is inscribed on one side of a lotus-shaped stone situated in a small Islamic cemetery known as Ujong Tanjong. The other side of the stone is inscribed in Jawi script, informing that Sulaiman bin Abdul Rahman bin Abdullah Nurullah died in the year 821 (1418–19).8Shariffuddin and Nicholl suggested that the Sanskrit and Jawi inscriptions may be contemporaneous with one another, perhaps the ‘work of the same artist’, which appears unlikely.9 The second short Sanskrit inscription found in Brunei, at the Islamic Dagang Cemetery, is inscribed on what may have been a sandstone stupa of slightly over a metre in height; it is again Buddhist, and makes brief reference to karma.10 The ‘stupa’ probably came to be used as a tombstone before being replaced by another stone.11 The Limbang inscription found at Buang Abai is similar to the Dagang ‘stupa’ in that it too refers to karma and is engraved on a similar structure (‘stupa’?) that had become an Islamic gravestone.12 Like the more extensive and permanent inscription of Batu Pahat in West Kalimantan, the three northwest Borneo inscriptions lack archaeological context, and hence are difficult to date. Furthermore, they also appear to have been transported to the locations where they were discovered from other locations in order to be used as Islamic gravestones.

Jan Christie has argued that these Borneo Buddhist inscriptions are related to the various Buddhist inscriptions of the Muda-Merbok estuary of Kedah on the Malay Peninsula that dates from the fifth century. The script and Buddhist content are similar, and the karma formula of the inscriptions appears to have been popular for a brief period then. Christie further argues that the ‘communities or individuals’ who produced these inscriptions were linked in some way to a Buddhist traders’ cult based on a central cult site in Kedah.13

Are the short Brunei and Limbang inscriptions evidence of a link, probably short-lived, to a Buddhist traders’ cult some time in the mid-first millennium? While this is a possibility, the fact that the stones with the inscriptions were brought to their present locations for use as Islamic gravestones makes it problematic to draw such a conclusion without supporting archaeological data and supplementary evidence. What is clear is that the Buddhist inscriptions at Batu Pahat, Brunei and Limbang are wholly dissimilar in nature to the fourth-century Hindu inscriptions of Kutai. Unlike Kutai, they were not created in the context of ‘state formation’, and on their own would provide no evidence of a polity even if the locations for the Brunei and Limbang inscriptions were fixed. Furthermore, given the very specific nature of the inscriptions, they do not appear to be related to other and more substantial evidence of Indic influence found in northwest Borneo dating to the second millennium, mainly in the Santubong and Limbang areas (see below).

That there is no archaeological evidence for the development of any complex societies along the northwest coast of Borneo before the tenth century, or of external trade in the first millennium, is consistent with Wang Gungwu’s detailed account of the Nanhai trade during the Tang (618–907) and earlier periods, which suggests that Borneo, the Philippines and Sulawesi played little or no role in this trade.14 Some writers have, however, attempted to identify pre-tenth-century toponyms mentioned in Chinese sources with parts of Borneo, including the northwest coast. Such identifications are at best speculative, not supported by archaeological data, and the toponyms have, and continue to be, associated with numerous places throughout Island Southeast Asia.15

As Munoz points out, many historians who have attempted to locate early toponyms in Chinese sources have used the highly unreliable method of trying to identify locations by analysing the length of time it took to sail from one place to another. The problem with this method is that journey times contain many variables: different captains, different types and sizes of ship travelling at different speeds, the seasons and ‘meteorological conditions’.16

Poli, which Robert Nicholl attempted to identify as a precursor of Brunei, is a particularly good example of the confusion and controversy surrounding the identification of places in Chinese sources.17 Wolters briefly reviews the numerous identifications that had been made by 1967:

Wolters himself considered that Poli ‘could not have been anywhere but in Java’, and probably east Java.19 Since then, different scholars have continued to make similar ...