![]()

1 Introduction

Peeling wallpaper

One of the main strengths of the arts is an ability to provide new perspectives on the lived world, often leading to a ‘startling defamiliarisation with the ordinary’ (Greene 2000, p. 4). Employed in the research process, the arts enable an examination of the everyday in imaginative ways that draw attention to the cruelties and contradictions inherent in neoliberal society. It is too easy to become inured to our surroundings, to forget how much we do know (however partial or limited this knowledge may be) and what our own day-to-day realities tell us about the wider world:

I put a picture up on a wall. Then I forget there is a wall. I no longer know what there is behind this wall, I no longer know there is a wall, I no longer know this wall is a wall, I no longer know what a wall is. I no longer know that if there weren’t any walls, there would be no apartment. The wall is no longer what delimits and defines the place where I live, that which separates it from the other places where other people live, it is nothing more than a support for the picture. But I also forget the picture, I no longer look at it, I no longer know how to look at it. I have put the picture on the wall so as to forget there was a wall, but in forgetting the wall, I forget the picture too …

(Perec 1974/2008, p. 39)

This habituation acts as a barrier in terms of understanding the profound inequalities of the social world and in acting to make positive changes. The minutiae of our lives, even down to our very feelings about them, are continuously being shaped by powerful socio-economic structures. Whilst we remain unquestioning, the ‘infinitesimal practices’ that ‘hegemonic or global forms of power rely on’ (Foucault 1980, p. 99) remain unnoticed.

Everyday life is ‘marked by difference’ (Highmore 2002a, p. 11). There are complex, interconnected ways in which ‘discrimination reaches into everyday lives providing a pecking order based on class, “race”, gender, age, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, “dis”ability or any other form of difference’ (Ledwith and Springett 2010, p. 27). Arts-based research methods enable a diversity of experiences to be communicated in ways that disrupt ‘common sense’ understandings and act as a reminder that there are possibilities for things to be otherwise. It is here that there are possibilities for small but significant acts of resistance and this enables Susan Finley (2008, p. 72) to proclaim, ‘At the heart of arts-based inquiry is a radical, politically grounded statement about social justice’.

The arts also lend themselves to collaborative working and the control participants have over the research process is central to the transformative potential of this methodology. Elliott Eisner (2008a, p. 10), a leading protagonist of arts-based research, describes his vision of a practice that is ‘considerably more collaborative, cooperative, multidisciplinary, and multimodal in character’. He continues: ‘Knowledge creation is a social affair. The solo producer will no longer be salient’. A collaborative research process offers opportunities to raise critical consciousness, highlight social relations and to promote deeper understanding among participants, facilitators and audiences. This understanding is built on ‘emotive, affective experiences, senses, bodies, and imagination and emotion as well as intellect’ (Finley 2008, p. 72).

This book explores alternative ways of working with marginalised people to produce knowledge about their lives; knowledge that can draw attention to their lived experience of inequality or stigma and be used to make positive transformations. It advocates a range of arts-based methods to collect, analyse and disseminate data. These methods draw on the literary, visual and performing arts and include storytelling, poetry, crafts, photography, digital technology, collage, short-film making and performance. Such eclectic devices offer ways of ‘knowing the self and exploring the world’ (Knowles and Thomas 2002, p. 131) in ways that make research accessible outside the academy. This chapter employs a variety of arts-based examples to make a case for the importance of this approach to social inquiry. It then provides a summary of the book and an outline of the forthcoming chapters. The section ‘Resistance buried in the everyday’ discusses how the everyday, the habitual, can be understood as a source of oppression and also of resistance. A provocative art work provides an illustrative example. The next section, ‘Listening with our eyes’, explores the need for research practice to attend to the unspoken elements of people’s experiences. The arts might enable a move away from a focus on the verbal and the textual, but there is also a requirement to make connections between these personal experiences and wider social relations. The third section, ‘Imagining freedom’, considers the role of the imagination in research that attempts to promote social justice, and argues that this is intricately entwined with our everyday realities. The act of creatively and collectively exploring our lives enables an acknowledgement that ‘Walls protect and walls limit’ (Winterson 1985). We need to look beyond them, and doing this in imaginative ways can be subtle, illuminating or even profound. It can ‘help us to see the actual world to visualise a fantastic one’ (Warner 1995, p. xvi).

Resistance buried in the everyday

There is a significant and fascinating history of studying the everyday (Highmore 2002a; Highmore 2002b; Sheringham 2006). Much of this centres on the French movement of la vie quotidienne, which includes the work of sociologists Henri Lefèbvre and Michel de Certeau, the writer Georges Perec and surrealists such as André Breton. Through surrealism, which Highmore (2002a, p. 46) reads as ‘a form of social research into everyday life’, there is a potential to tap in to ‘the unrealized possibilities harboured by the ordinary life we lead rather than rejecting it’ (Sheringham 2006, p. 66). Bizarre poetic encounters and strange juxtapositions of everyday objects become ‘important artistic strategies that destabilise and cast doubt on the objectivity and conventions of “reality”’ (Schulz 2011, p. 14).

One notable interdisciplinary way that this can be seen is through the Mass-Observation project that began in the 1930s in the UK. Founded by Charles Madge, Tom Harrison and Humphrey Jennings, it produced an ‘unlikely and disquieting marriage of surrealism and social anthropology’ (Highmore 2002a, p. 31). This was an ‘anthropology at home’ in which members of the public were able to take part. They were recruited and sent out to record their domestic cultures through ethnographic methods of observation and diary-keeping in an arguably ‘radically democratic project’ (Highmore 2002a, p. 87) that let people ‘speak for themselves’ (Highmore 2002b, p. 145) and provide a commentary on everyday life with the potential of making changes to it (2002a, p. 111).

In its original manifesto, Mass-Observation produced a list of topics for investigation (Harrison et al. 1937, p. 155, cited in Mengham 2001, p. 28):

Behaviour at war memorials; Shouts and gestures of motorists; The aspidistra cult; Anthropology of football pools; Bathroom behaviour; Beards, armpits, eyebrows; Anti-semitism; Distribution, diffusion and significance of the dirty joke; Funerals and undertakers; Female taboos about eating; The private lives of midwives.

The ‘sheer daftness’ of the list is ‘in perfect accord with the more facile subversions of surrealist humour’ (Mengham 2001, p. 28) but remarkably the idiosyncratic project grew into a well respected enterprise (ibid., p. 27). Through the continuation of the avant-garde practice of making the familiar strange, emerged a ‘popular poetry of everyday life’ (Highmore 2002a, p. 111) which anticipated the later concerns of reflexive ethnography (Clifford 1988, p. 143) in terms of its preoccupation with multivocality and poetic representations.

In order to attend to issues of social justice there remains a pressing need to view the everyday from an alternative angle, and to ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant’ (Emily Dickinson, in Franklin 1998, p. 506). It is through the everyday that the ‘endless “quiet” reproduction’ of social norms takes place. It is in the everyday that the ‘most trenchant ideological beliefs, the most hard-to-fight bigotries’ lurk (Highmore 2005, p. 6). Perec’s work on the ‘infra-ordinary’, as well as attending marvellously to the peculiarities of la vie quotidienne, highlights the political importance of questioning the habitual:

But that’s just it, we’re habituated to it. We don’t question it, it doesn’t question us, it doesn’t seem to pose a problem, we live it without thinking, as if it carried within it neither question nor answers, as if it weren’t the bearer of any information.… In our haste to measure the historic, significant and revelatory, let’s not leave aside the essential: the truly intolerable, the truly inadmissible. What is scandalous isn’t the pit explosion, it’s working in coalmines. ‘Social problems’ aren’t ‘a matter of concern’ when there’s a strike, they are intolerable twenty-four hours out of twenty-four, three hundred and sixty-five days a year.

(Perec 2008, p. 209)

Ideology, or the ‘stories a culture tells about itself’ (Lather 1991, p. 2), permeate our everyday experiences. These stories are interwoven through our social and cultural lives, their transmittance often unconscious and inarticulate. Terry Eagleton (2007a, p. 114) poses the question of how we combat a power that is ‘subtly, pervasively diffused throughout habitual daily practices’, power which has become the ‘“common sense” of a whole social order, rather than one which is widely perceived as alien and oppressive’.

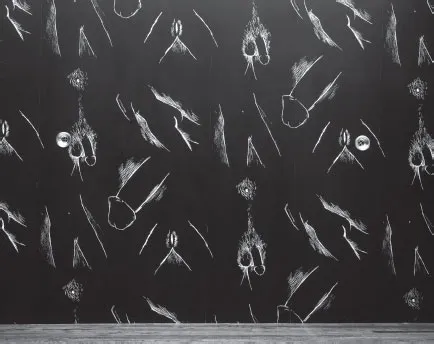

Yet if the everyday is a source of oppression, it is also in the everyday that resistance is embedded, ‘buried in everyday activities’ (Weitz 2001, p. 667). A recent exhibition at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery, ‘Walls Are Talking: Wallpaper, Art and Culture’, provides a series of potent examples of how the everyday domesticity of wallpaper, this ‘“merely” decorative … innocuous backdrop to our lives’ whose ‘very ubiquity renders it invisible’ (Woods 2010, p. 12), can be subverted in order to rupture complacency. The exhibition presents avant-garde work from a range of artists who have produced wallpapers with their own designs, patterns or motifs. Robert Gober’s series of installations consists of wallpapers printed with disturbing, provocative images. Male and Female Genital Wallpaper, as the title would suggest, comprises recurring images of genitalia (Figure 1.1). They are sketchily drawn and would look more in keeping scratched into the door of a public toilet cubicle than on a vast expanse of wall in the rarified gallery setting. Yet it is precisely this disturbing of context that communicates Gober’s message concerning the ways that sex and sexual identity are kept hidden and private. The work was first produced in 1989, at the peak of the AIDS crisis, a time when sexual practices did begin to be discussed more publicly. However, a downside to this was an increased and blatant discrimination of gay men (Saunders 2010, p. 34). The very way that wallpaper envelops the room, and is a constant background to daily life, is an important factor in Gober’s work. The use of those troubling images, repeated over and over again draws attention to the ways in which ‘social, sexual and political attitudes and codes of behaviour become ingrained by a process of repetition and familiarization so insidious and stealthy that we neither notice nor question them’ (Saunders 2010, p. 33).

The consciously political, emancipatory knowledge that this book focuses on draws attention to such ‘contradictions distorted or hidden by everyday understandings’ (Lather 1991, p. 52) and to the possibilities for social change. Processes of knowledge production do not stand outside ideology, but they do hold potential for challenging the status quo. Such a challenge requires ‘a different way of making sense of the world’ (Ledwith and Springett 2010, p. 160).

Figure 1.1 Robert Gober, Male and Female Genital Wallpaper, 1989, silkscreen on paper, 15’ × 27”, edition of 100

Source: © Robert Gober, Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Listening with our eyes

Whilst the collaborative approach suggested in this book draws on the experiential knowledge of the subaltern, there is a tension in terms of assuming people are ‘experts in their own lives’. Indeed, Les Back (2007, p. 11) is particularly dismissive of this notion, arguing that the ‘up close worlds that people experience combine insight with blindness of comprehension and social deafness’. In The Art of Listening (2007), Back calls for a sociology that listens much more vigilantly, but also engages critically with what is being said. Although his methodological approach is quite different from the one outlined here, his work holds much resonance for this book. Back’s raw but beautifully nuanced accounts of violence and pain weave together people’s stories and images with sociological rigour. The tattooed man lying in a hospital bed, voiceless, dying, the ink telling the story of his journey around the world as a merchant seaman; the brashly styled, ‘larger than life’ Black woman who calls everyone ‘Honey’ yet whose confident demeanour hides ‘confidential frailties’ (ibid., p. 106). A palpable respect is demonstrated for the subjects of his research, and thoughtful links are made between the ‘traces that they leave’ (ibid., p. 153) and global political forces. Back employs images that are powerful and haunting, images that call for us ‘to listen with our eyes’ (ibid., p. 100).

Listening is certainly a key element of social justice oriented research, and this is not necessarily an undemanding process, as the Italian philosopher Gemme Corradi Fiumara discusses in The Other Side of Language (cited in Kester 2004, p. 107):

We have little familiarity with what it means to listen, because we are … imbued with a logocentric culture in which the bearers of the word are predominately involved in speaking, molding, informing.

Listening with our eyes requires an attention to nuances, silences, embodied feeling, and also making links with wider social injustices. Purabi Basu’s lyrical short story ‘French Leave’ (also sometimes translated as ‘Radha Will Not Cook’) addresses the daily chore of cooking which still largely falls to women across much of the globe. It tells of a woman, Radha, who awakens one morning and decides not to cook that day. Her family is horrified when she refuses to provide any meals. Her mother-in-law’s ever shriller weeping and wailing is loud enough to attract the neighbours’ attention. Rhada’s husband shakes her shoulders ‘violently’ and smashes crockery around her. Radha remains silent and unmoved throughout this cacophony:

Radha went and quietly sat on the steps leading down to the pond, dipping her feet in the water. Behind her the voices were not merely in chorus; they were shouting the house down.

(Basu 1999, pp. 10–11)

Poetic images abound throughout the story. The natural world surrounding Radha is in rhythm with her rebellion. Flowers toss their heads; little waves break upon the edges of the pond ‘in chuckles’. The story closes with Radha gathering her son to her bosom and breastfeeding him. Four-year-old Sadhan is unused to this, as is Radha’s body, but before long ‘bubbling white milk’ is flowing from the child’s ‘busy lips’ and Radha is satisfied with her resolution not to cook.

Swati Ganguly and Sarmistha Dutta Gupta (cited in Singh 2009, p. 2) trace the appeal of the story to ‘the subtle way in which such subversive potentials are teased out in a narrative’. Basu’s light touch belies the simmering layers of injustice that have led to Radha’s subservient position, and the potency of her resistance and transformation. Whilst the body, grounded in everyday life, may be understood as a vehicle for oppression, so can rebellion be seen in Radha’s bodily responses to the novel situation she has created. As Simon Williams (1998, p. 438) argues, ‘Bodies, in short, from their leaky fluids to their overflowing desires and voracious appetites, are first and foremost transgressive: demonstrating their continual resilience to rational control’.

Madhu Singh (2009, p. 8), drawing on Scott’s (1985) work on everyday resistance, acknowledges the power that Radha’s silence conjures. Not only is it a ‘bold step against social convention’, it also highlights the plight of women who are ‘obliged to remain silent and suffer without protest’. Silence can be seen as a form of dissent but there is a paradox here, given that there is much emphasis in social justice orient...