1 SOUNDING OFF: AIMS AND APPROACHES

Our Margit declared if hoo’d clo’es to put on,

Hoo’d go up to London to see the great mon,

And if things wur not altered when there she had been,

Hoo swears hoo would fight wi’ blood up to the een.

Hoo’s nowt agen th’ king but hoo likes a fair thing,

An’ hoo says hoo can tell when hoo’s hurt.

We’re all sick of the public spending cuts.

Public spending cuts, public spending cuts …

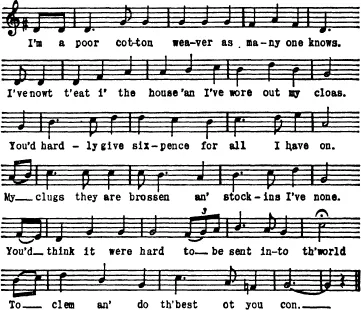

These two extracts seem worlds apart. The first, from the trauma of the first 40 years of the nineteenth century and perhaps written by an Old-ham weaver like the one whose story the song tells, records the demise of a pre-industrial group, albeit a militant, articulate and (for its time) politically sophisticated one. The second extract is of our own time (which some sociologists have already begun to call ‘post-industrial’) and is also anonymous, but could have been written by a welder, student, housewife or postal worker. In the first song an individual (if typical) fate is unfolded; the second rejoices in collective struggle. Poor Cotton Weaver is written in the traditional mode of English folk song and its singability has survived a century and a half; Public Spending Cuts is sung to a 1960s pop tune and makes no claims to survive the campaign for which it was written. In form and content the songs appear alien to one another, yet this book is an attempt to trace the thread linking them in a tradition of song written in, around and for the working class and the fight for democracy in Britain since industrialisation.

Song and Democratic Culture is an attempt to combine cultural theory, cultural history, literary criticism (in its application to song) and the cultural praxis of social movements. One primary scholarly task is to link up with the growing debate in Britain on cultural studies, and especially working-class culture, and to offer a fresh theoretical approach to the relationship between ideology and culture (as the formal artistic, institutional, etc. expression of ideology) as well as to the writings of Antonio Gramsci, re-discovered a decade ago as a central contribution to ideological and cultural studies.

Song as a continuing but changing cultural force is the book’s paradigm – a typical example from which to draw general conclusions. The historical dimension of the study spans two centuries – from the merging of the rural folk culture into the new conditions of industrial Britain through to the pockets of songwriting to be found today. The central question of what has happened to songwriting by members of the working class since the boom of industrial folk song in the middle of the last century is coupled with the problems which weld cultural theory and history. Did – as Martha Vicinus claims – workers’ culture drift from a ‘class culture to a mass culture’ in the wake of the Victorian entertainment industry? What is ‘working-class culture’ in any case? Were the folk song revivals rank-and-file movements – and, in as far as they were not, what relevance did they and can they have for an autonomous, consciously working-class song culture?

The question of cultural tradition is linked to the problem of artistic form. How has a song type which was, after all, the product of the rural working class, a social group superseded in its national cultural importance, survived the double onslaught of urbanisation/industrialisation and commercial mass entertainment – even if only in pockets? Industrial folk song acts here as a springboard. Working out of the folk tradition, the study offers first suggestions, perhaps in part controversial, towards aesthetic criteria (both form and content-orientated) for assessing songs. Song assessment means, firstly, selection from and rediscovery of the existing heritage of song for relevant enjoyment today.

Aesthetic criteria are, secondly, guidelines for writing new songs. On the practical side, the book explores an area in which fruitful artistic work is being carried out on a small scale. Macropolitical songs as well as realistic songs of everyday life, work and the struggle for survival are being written and sung by semi-professional and leisure-time songwriters all over the country, most of them isolated individuals in search of co-ordination, exchange, discussion, yardsticks, encouragement and a common voice – in search of a movement. For these songwriters and for collectors, singers and above all teachers the book offers a first point of reference.

Thus Song and Democratic Culture has, both in theme and presentation, been geared to appeal to and reconcile a variety of readership groups, both scholarly and non-scholarly, who may not always be easy to reconcile. The balance of theory and practice, although essential to the tasks, is hard to keep in style, approach and presentation, so I ask the (practical) ‘song’ reader and the (theoretical) ‘culture’ reader to be tolerant of each other’s needs and of any unevenness which the consideration of both has brought about.

Coming from outside, I make no claims to put the house of the folk club movement in order, yet I know the revival well enough to be able to distinguish trends which I see as detrimental to the healthy conservation and promotion of an important part of the heritage. There is, first of all, the faction in the revival which sees the collection, performance and enjoyment of folk music more and more as an esoteric occupation, with its resultant purism, academicism and snobbery. Then there is ‘folk’ as an elitist branch of pop, geared to a predominantly student market, with new groups or singers enjoying a small cult following. Working-class music has become in many places a middle-class hobby. As a result, a large number of ordinary working-class people are alienated by the cults of dress, behaviour and age from going along to a folk club and enjoying what is, after all, in historical terms, their own music. The repertoire of many folk song performers has been reduced to the purely divertive song: either of the drinking and wife-bashing variety or love songs of the ‘green willow’ type which were the stock-in-trade of the Edwardian collectors. Songs of a political or socio-critical nature are becoming rare in many clubs. Here again, old songs are favoured; despite the work of the post-war collectors, the idea that folk song stopped with industrialisation is still widespread. Against such trends, this book hopes to show that the performance and enjoyment of folk song is the heritage of working people; that folk song is entertaining and linked to the way we still live today; and that it is a living tradition, enriched by the history of the last 150 years. In carrying out these tasks I may step – and without apology – on some folk-scene toes. The hope, however, is to give folk singers a lead and to encourage more of them to sing newer, more political and working-class orientated material, and to reflect on who they wish to reach with traditional folk music and the best of contemporary song writing. In this context it is important to transcend the formalistic mud-flinging which split the folk song revival into sham factions accusing each other of romantic Lud-dism, proletcultism, commercialism or opportunism respectively.

Perhaps the bulk of the task of promoting a new song movement linked to social movements will prove to be rooted in areas born out of the electronic media, both in terms of their making (rock music) and their distribution (records). Yet up to now, as Dave Harker has pointed out in One for the Money, rock music with a political or even mildly socio-critical potential has, time and again, been defused by the pressures of commercial conformity and by the deification and cocooning of its stars away from their paying public. So this study pleads for a plurality of song types and seeks to show that alongside the mainstream electronic forms there is still room for the sparsely accompanied singer-songwriter whose task is communicating text, and for the small-audience, participatory tradition which is seen as the continuation and further development of the old folk-culture structures. However, faced with the disappointing demise of the folk clubs as a real cultural force, the book attempts to reassess the potential of an older cultural form for new songwriting inside and outside the working class. So by exploring the history and function of the folk-song culture, the book outlines a continuity of certain traits, ideological and aesthetic, which still form a workable basis for songwriting in a changing world.

I am attempting to redress a cultural balance which has long been tipped in favour of those who believed in imposing the artistic creation of the few as the cultural norm and model for the many, who argued that the workers had no artistic culture and needed ‘leadership, contact with the upper classes, and an awareness of art, books and music’.1 I had two scholarly starting-points for this.

In The Real Foundations (1973), David Craig briefly handled songs of the Industrial Revolution and named indices for a rebirth of the tradition, quoting examples from the 1950s. This chapter – written in 1967 – represents a first attempt to categorise the tradition and to link analyses of song with social history, albeit with the emphasis firmly on the nineteenth century.

The great modern classic work is A.L. Lloyd’s Folk Song in England (1967), in the long last chapter of which he defined and assessed industrial folk song by concentrating on the examples of the mining and textile industries. Lloyd’s book is the point of departure for all further studies. The groundbreaking and seminal nature of his chapter has thrown up basic problems and some contradictions which are to be seen as the genesis of the present study.

Lloyd’s work must be coupled with a theoretical treatment of the problems of working-class culture under the conditions of large scale industry, imperialism and monopoly capitalism. In addition, the question of aesthetic evaluation must be reviewed. We need a set of acceptable criteria which will not only allow a more satisfactory selection and assessment of the tradition, but guide the writing of new songs.

Folk song in England was published in 1967; the 1975 edition remained unrevised. It was written at a time of relative calm, mingled indeed with pessimism and resignation, in the British Labour Movement. Since then, the panorama of the British working class -- and its songs – has altered radically. We need to consider the considerable cultural activity of the last decade.

Lloyd has put the bulk of his effort into researching miners’ songs and, within this framework, concentrated on the North-East of England. By concentrating on the most prolific region of the most prolific --because oldest – industry, Lloyd has provided an uneasy yardstick for collecting and assessing songs from other areas and other industries (canals, railways, engineering as well as newer industries like chemicals and electronics). While concern with North-East England has been fostered by Harker, Colls and others, fieldwork in other regions has shown digressions from the picture of industrial song reinforced in the 1960s and 1970s primarily by Lloyd. This has been the case both with songs of the Victorian cities as well as with post-Sharp/Lloyd studies of rural culture, as for example by Vic Gammon. As far as living songwriters are concerned, Lloyd’s published material is restricted to mining.

The best regional study so far is Jon Raven’s The Urban and Industrial Songs of the Black Country and Birmingham, which builds on earlier books. Although, as a result of its specialisation, it has played only an ancillary role for the present study, it is an exemplary model for an overdue comprehensive nationwide recording of industrial song up to 1900. (One particular interest it has for a national project is that it features an area which has a clear regional identity and a large fund of songs from a variety of old and new industries but was almost overlooked by the folk song revival of the 1950s and 1960s.)

Scotland plays an important role in this study. While most song scholarship has been concerned primarily with the English Midlands and North, I have drawn on a small but vital working-class and political culture based around Glasgow which includes song derived from folk and other sources. Not only are our two examples of a worker and a ‘professional’ writer, Jim Brown and Ewan MacColl respectively, Scots, but it is also no coincidence that our model for trade-union support of song in the last chapter is Glaswegian.

Finally, this study differs from Lloyd’s in one central cultural-political aspect, since he restricts his attention to industrial folk song, to ‘vernacular songs made by workers themselves directly out of their own experiences … The kind of songs created from outside by learned writers, on behalf of the working class, is not our concern here.’2 In contrast, the following pages will seek to analyse the relationship between industrial folk song and other song types which have become increasingly relevant to the labour and progressive movement over the last decade: ‘social’ or ‘contemporary’ songs, written for a specific, socially-critical purpose, usually by a (semi-) professional songwriter; and mainly agitational ‘pressure-group’ songs on either community issues or on larger political problems. So the basic cultural-p...