- 596 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to World Politics

About this book

Originally published in 1922, An Introduction to World Politics, was published at a particularly interesting time in international relations, just a few short years after the first world war. With this in mind, Gibbons has approached this text as a general introduction to world politics, both examining causes of recent events in his lifetime as well as exploring what he refers to as 'the beginning' of World Politics. This study delves into various aspects of world politics throughout history including the colonialism of the British and the French and several wars and treaties with analysis on how this impacted on relations between nations. This title will be of interest to students of Political History and International Relations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to World Politics by Herbert Adams Gibbons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER III

THE RISE OF WORLD POWERS (1848–1878)

AT Paris in January, 1919, plenipotentiaries of twenty-seven states gathered to decide upon conditions of peace to be imposed upon Germany and the allies of Germany. In preliminary private conferences the representatives of France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, and the United States, without so much as “by your leave,” organized the work of drafting the treaties in such a way as to exclude the other states from any real voice in the deliberations. “The Principal Allied and Associated Powers with general interests” allotted themselves two members each on every committee and on the Council, which was to be the final court of decision. “The Secondary Powers with particular interests” were granted no representation on the Council, and were told that they would have to designate five members—to represent them all together—on the committees. Despite vehement protest and sulking, this plan was carried through. The great powers had won the war and would be responsible for enforcing the peace. Therefore, it was argued, they must keep in their hands the right to decide upon the terms of the treaties and the right to interpret them afterwards.

This was not a new idea. It followed the tradition and practice of nineteenth-century diplomacy, begun at the Congress of Vienna and developed at the congresses of Paris (1856) and Berlin (1878). The only change was the exclusion of Germany and Russia and the inclusion of the United States and Japan. Because of the size of their armies and navies, and their success in using them, certain nations have long assumed the privilege of settling questions arising from war according to their own interests and at the expense alike of defeated nations, of weaker allied nations, and of neutrals. During the hundred years between the Napoleonic wars and the World War, this privilege had been gradually extended to cover every question affecting the general welfare of mankind. The world powers were alone capable of waging war; hence the peace of the world could be maintained only through agreement among themselves. The aim of diplomacy was to satisfy the world powers; the destinies of other nations and races, their liberty, their security, their prosperity, their general well-being, were subordinated to the policies and ambitions of the world powers.

The defect in the scheme lay in the inability of the world powers to satisfy one another. They fell out singly, and then sought to form combinations. From coalitions made for particular wars and terminating automatically when peace was signed, they were led into alliances contracted in time of peace to protect and advance their interests in different parts of the world. New causes for friction arose, which had little or nothing to do with the normal relations between nations.

Before 1848 the chief concern of the powers, in their relations with one another, was the preservation of the status quo of the act of Vienna. Monarchs and statesmen were afraid that the democratic movement, if successful in other countries, would react upon the internal situation in their own country. Neither Russia nor Austria could see new states born of the revival of subject races without feeling that the precedents shook the foundations of their own power. The breaking away of Belgium from Holland in 1830 was more than a breach of the act of Vienna. It gave hope to the partitioned Poles, and encouraged the fermentation in the Italian and Balkan peninsulas. The separatist movement in Hungary reacted almost as dangerously upon Russia as upon Austria. But after the failure of the revolutions of 1848 the powers began to realize that their chief danger was from the intrigues of neighboring powers. Revolutionary movements could hardly be successful unless encouraged and supported by an interested outsider. Separatism was doomed to impotence if the nations affected were allowed a free hand to suppress it. The aid given by Russia to Austria against Hungary in 1849 was the last attempt to attain what the Holy Alliance called its main object, i. e., international coöperation against subversive internal political movements.

The revolutions of 1848 were weathered everywhere in Europe except in France, where the Orléans dynasty fell and a republic succeeded in establishing effective administrative control. The French republicans, however, realized that the national interest required continuing the foreign policy of the ousted régime. Principles and ideals, in the industrial era that was just dawning, could not be subordinated to quixotic sympathy with peoples struggling for the same principles and ideals in another country. Accordingly an army was despatched to Italy, which put an end to Garibaldi’s Roman republic in the late spring and early summer of 1849. It was the same test as that of 1830. The ministers of Louis Philippe did not interrupt the expedition begun by the ministers of Charles X in Algeria. Moreover, although they were in power because of a revolution undertaken in the name of liberty, they resisted every effort of generous-minded men to have France intervene in favor of the Poles. The famous response to a question asked in the Chamber of Deputies about Poland, “Order reigns in Warsaw,” has never been forgotten. Convinced of the necessity of a foreign policy based on national interest, the French people thereafter allowed no internal disturbances or changes in government to affect the ministry of foreign affairs. Imperial or republican, clerical or anti-clerical, idealist or realist, the governments of France since 1848 have made moves and taken positions in international politics with one purpose, to protect and increase what were believed to be the commercial interests of France abroad.

This new attitude, which is the inciting motive in world politics, entered into the aftermath of the Revolution of 1848 in Germany. The preliminary parliament in Frankfort decided to call a national German assembly for the purpose of making a constitution for a new German Empire. The troops of the German Confederation were loyal to the principle of unity. We can not understand the involved struggle in the German states, and the influences at work in the parliaments of Erfurt and Frankfort in 1850, by the sole factor of the rivalry of Prussia and Austria for hegemony. Nor can we consider the failure of the revolutionists, most of whom emigrated to the United States, as due to the single cause to which they attributed it. The triumph of reaction was temporary. The great mass of the German people did not abandon the revolution and frown upon republicanism merely because of an inherent conservatism. The new industrialism, and the vistas of opportunity opened up by the development of railroads and ocean commerce, made the Germans think of unity as the summum bonum. It is the commonly accepted idea that in the generation following the Revolution of 1848 a ruthless Prussia, under the direction of Bismarck, stamped out her own liberties and those of her neighbors for the glorification of a dynasty and a caste. But this does not take into account the irresistible economic current that influenced the political evolution of central Europe during the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

Unless the Germanic peoples were willing to see themselves doomed to permanent inferiority in the new Europe, they too had to unite and become a world power. Railroad construction required capital and continuity. There must be free access to coal and iron, common protection against foreign goods for the development of industries, and a united effort to bring into the country raw materials, and to find, all over the world, markets for manufactured articles. The Germans, the peoples of the Danube, and the Italians were faced with entirely new economic conditions in the struggle for existence. There was no alternative to the formation of large political organisms.

The unification of Germany and Italy and the reorganization of the Hapsburg dominions in a dual monarchy were events beyond the power of statesmen to cause or prevent, or even greatly to control. While it is far from our intention to attribute the unifying processes in the three central European countries to conscious world policy, it is none the less true that when European powers became world powers it was inevitable that there should be a Germany, an Italy, and an Austria-Hungary. Although it is doubtful whether statesmen or people appreciated the full extent of their handicap in a world so completely transformed since 1815, they did appreciate the handicap of lack of unity upon the development of industry and transportation facilities within their own borders and with neighbors of the same blood, language, and culture. In the process of erecting political organisms that would enable the peoples of central Europe to hold their own with those of western and eastern Europe in the new era of extra-European expansion, Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, and Italians fought one another with the aid of the already unified powers. And during the same period the inhabitants of the United States were engaged in a deadly civil war for the same purpose of unification. The conflict between states’ rights and federalism came to a head in the New World, in South America as well as in North America, during the decade when the Old World was successfully forming centralized states. The same struggle for centralization was going on contemporaneously in Japan.

Great Britain, France, and Russia were ready to meet the new conditions, and their rise as world powers was not marked by internal or external convulsions. They were ahead of the other nations, and this advantage they kept. Ultimately they formed a natural alliance to defend against the later claimants the privileged position won through their geographical position and their earlier achievement of political unity.

The significant events in the preparation of the other great states to rise to world power may be briefly reviewed.

The German Empire was created through the activities of Prussia, who took these successive steps: (1) foundation, in 1828 and 1833, of the German customs union (Zollverein), which Prussia had been advocating since 1818; (2) reëstablishment of the German Confederation of 1815 at Dresden in 1851; (3) war, along with Austria, against Denmark, resulting in the termination of Denmark’s rights over Schleswig and Holstein in 1864; (4) alliance with the smaller north German states and Italy against Austria and the south German states, which were defeated in the war of 1866; (5) expulsion of Austria from the Germanic Confederation, followed by the incorporation of some small German territories in Prussia; (6) establishment, under Prussian leadership, of the North German Confederation, including all except four south German states; (7) war, with the aid of these south German states, against France, resulting in the seizure of Alsace-Lorraine and the creation of the German Empire in 1871.

Italy was created through the expansion of the kingdom of Sardinia and the unofficial activities (sometimes disavowed) of the revolutionist Garibaldi, involving these successive steps: (1) Sardinia, with France, fought Austria and annexed Lombardy in 1859, paying France by giving up Savoy and Nice; (2) Modena, Parma, and Tuscany, expelling their rulers, united with Sardinia in 1860; (3) Garibaldi invaded Sicily, passed to the mainland, and overthrew the kingdom of Naples, which voted to join the kingdom of Sardinia, also in 1860; (4) the kingdom of Italy was proclaimed at Turin on March 17, 1861; (5) Italy, with Prussia, fought Austria, and won Venetia by the peace settlement in 1866; (6) the Italian government seized Rome and the papal states in 1870, when the defeat of France by Germany forced the withdrawal of French troops which had been protecting the temporal power of the papacy during all the progress of Italian unification.

Austria-Hungary was created through the expulsion of Austria from the Germanic Confederation by Prussia in the war of 1866. Austria had been greatly weakened by the revolutions in Bohemia, Hungary, and her Italian possessions. The Hungarian revolution was crushed with the help of Russia in 1849, but Lombardy and Venetia were lost in the wars of 1859 and 1866. When Austria lost her position in the Germanic Confederation, she was no longer strong enough to cope with the different nationalities of the Hapsburg empire. Consequently the German element had to choose between the dwindling of the empire and division of power with other races. In 1867 a compromise was made with the Hungarians, by which the empire was changed into a dual monarchy. Hungary and Austria henceforth had the same ruler, but were largely independent of each other in internal affairs. The two equal partners, in turn, were left to make what compromises or arrangements they saw fit with other racial elements within their borders. The Austrians oppressed the Czechs and Italians, but gave virtual autonomy to the Poles, abandoning to them the Ruthenians (Ukrainians). The Hungarians granted a separate diet to the Croatians at Agram, but held down the Rumanians. This unique political organism could not be called a nation in the sense that Germany and Italy were nations. Its political existence seemed dependent upon the strength of Germany and the weakness of the Balkan States. But, although torn by nationalist movements, which each decade became more threatening, the polyglot dual monarchy managed to survive because of common economic interests and the advantage to the various peoples of belonging to a strong political organism able to face the competition of other world powers and to provide industrial and transportation necessities.

When she won her independence from Great Britain, the United States was a small country along the Atlantic coast, containing less than three million population. From the point of view of political unity and of development of national sentiment, the new republic was fortunate in its cultural and linguistic unity. The earlier immigration was mostly English-speaking, and the non-British portion was of the same north European stock as the original settlers. There were no serious problems of racial and religious antagonism. But the Union was formed on the basis of a voluntary confederation of states that had retained their boundaries and had surrendered only part of their governing powers to the federal government. Chiefly because of the slavery question the states of the North and the South gradually drifted apart. Because it was not profitable, slavery disappeared in the North. In the South it seemed indispensable to agricultural development. As the country grew by penetration and settlement westward, and new states were added, in most of which the holding of slaves was against public sentiment, the South fell more and more into the minority in the confederation. Fearing being overwhelmed and being deprived of their slaves, eleven of the Southern States attempted to secede from the Union. The Northern States denied the alleged right of secession, and a war of four years followed. Great Britain and France sympathized with the South, but did not intervene. The North won, and the unity and perpetuity of the United States were finally assured in 1865.

Japan was opened to foreign intercourse and trade by the intervention of the United States. From 1854 to 1858 the United States, Great Britain, France, and Russia succeeded in negotiating treaties of commerce with the “shogun,” whom the powers presumed to be the ruler of Japan. He was indeed the holder of secular authority, but the shogunate was a usurped position, in the hands of feudal lords. It had been held by one family for more than two hundred and fifty years, and other feudal families, who were dissatisfied, took advantage of the resentment against the shogun aroused by his yielding to foreigners to conspire against him. The result of the ratification of treaties extorted by the foreign powers was the resignation of the last shogun in 1867, and the resumption of government by the lawful sovereign, the mikado, in 1868. Civil war followed, in which the imperialists were successful. In 1871 feudalism was abolished, and Japan started upon a united political life. National self-consciousness was born of the instinct of self-preservation, and Japan began to imitate Occidental civilization in order to become a world power.

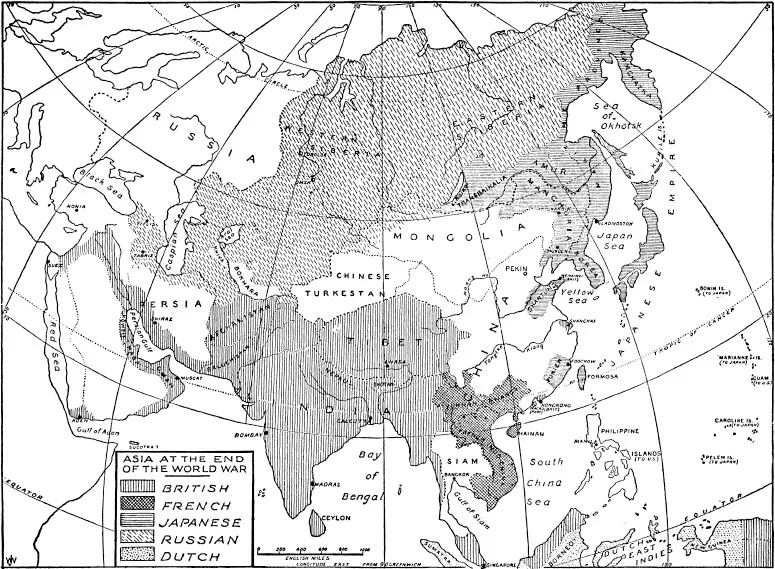

While the Germans and Italians were accomplishing their unification, and the Austrians and Hungarians were wrestling with the problem of forming a state, capable of maintaining itself as an equal among the world powers, in which the majority of the population was of other races, Great Britain, France, and Russia laid the foundations of their political influence, according to the new conception of that term, in the Far East and the Near East.

Great Britain began the policy, followed later by the other powers, of compelling China to cede territory and commercial privileges by force of arms. In 1834 Emperor Taukwang, alarmed at the evil effects of opium introduced into China by British traders from India, attempted to revive an edict prohibiting the opium trade. The moment was opportune, and no international agreement was violated, for the exclusive privilege of the East India Company had just expired. But the trade had become too profitable to lose. After several years of negotiations, the British declared war on China. The immediate cause was the refusal of the Chinese government to reimburse British merchants for the destruction of more than twenty thousand chests of opium landed on Chinese soil in defiance of the prohibition. Great Britain demanded also that the imperial edict be revoked and that trade be continued and protected. In 1842 China was compelled to sign the treaty of Nanking, by which the island of Hong-Kong was ceded to Great Britain; five ports were opened to British trade; and an indemnity was exacted. A supplementary treaty, signed the next year, established the five per cent. ad valorem tariff, and forced China to admit the principle of extraterritoriality.

In 1844 the United States and France succeeded also in making commercial treaties with the unwilling Chinese. There was a scramble for trade, into which Russia, beginning to penetrate from Siberia, entered. In 1856 a small Chinese sailing-vessel, owned by a Chinese but flying the British flag, was boarded by Chinese officers hunting for pirates. Some of the crew were arrested and the flag was pulled down. This incident led to a new declaration of war by Great Britain against China, in which France joined. The Chinese fleet was destroyed in May, 1857, and Canton was captured at the end of the year. Therefore, in 1858, the Chinese signed treaties with Great Britain, France, the United States, and Russia, promising a measure of protection to traders and ships, which the authority of the Peking government was unable to assure. By the treaties of Tientsin in June, 1858, the number of treaty ports was increased, French sovereignty in Indo-China was recognized, and the Amur Province was ceded to Russia. When a British ambassador attempted to go to Peking in 1859, and was fired at, Great Britain and France renewed t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Contents

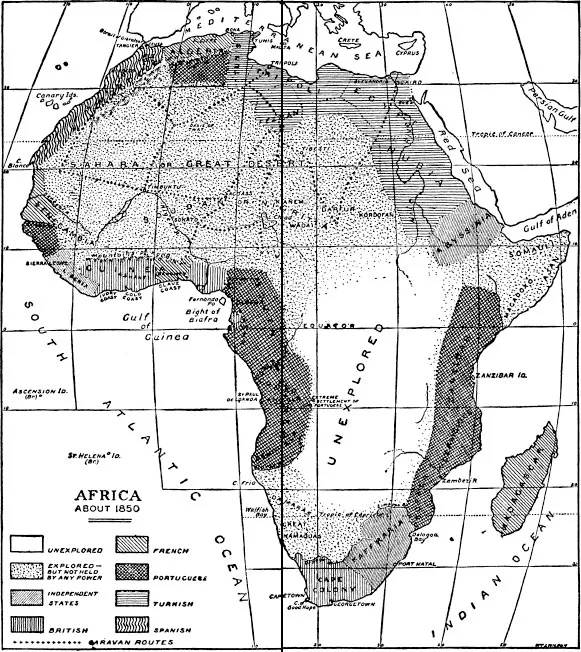

- Maps

- I The Beginnings of World Politics

- II Nationalism and Steam Power (1789–1848)

- III The Rise of World Powers (1848–1878)

- IV French Colonial Expansion (1830–1900)

- V British Colonial Expansion (1815–1878)

- VI Consolidation of British Power in the Near East (1878–1885)

- VII The Near Eastern Question (1879–1908)

- VIII Russian Colonial Expansion (1829–1878)

- IX Consolidation of Russian Power in the Far East (1879–1903)

- X Japan's First Challenge to Europe: The War with China (1894–1895)

- XI The Attempt to Partition China (1895–1902)

- XII Japan's Second Challenge to Europe: The War with Russia (1904–1905)

- XIII The Revival of British Imperialism (1895–1902)

- XIV Persia and the Anglo-Russian Agreement of 1907

- XV Egypt, Morocco, and the Anglo-French Agreement of 1904

- XVI The Development of the German Weltpolitik (1883–1905)

- XVII The Franco-German Dispute Over Morocco (1905–1911)

- XVIII The Young Turk Revolution and its Reactions (1908–1911)

- XIX Italian Expansion in Africa (1882–1911)

- XX The Reopening of the Near Eastern Question by Italy (1911–1912)

- XXI Intrigues of the Great Powers in the Balkans (1903–1912)

- XXII The Balkan War Against Turkey (1912–1913)

- XXIII The Balkan Tangle (1913–1914)

- XXIV The Triple Entente Against the Central Empires (1914)

- XXV Italy's Entrance into the Triple Entente (1915)

- XXVI The Alinement of the Balkan States in the European War (1914–1917)

- XXVII China as a Republic (1906–1917)

- XXVIII Japan's Third Challenge to Europe: The War with Germany and the Twenty-One Demands on China (1914–1916)

- XXIX The United States in World Politics (1893–1917)

- XXX The United States and the Latin-American Republics (1893–1917)

- XXXI The United States in the Coalition Against the Central Empires (1917–1918)

- XXXII The Disintegration of the Romanoff, Hapsburg, and Ottoman Empires Through Self-Determination Propaganda (1917–1918)

- XXXIII The Attempt to Create a League of Nations at Paris after the Defeat of Germany (1919)

- XXXIV The Refusal of the United States to Ratify the Treaties and Enter the League (1919–1921)

- XXXV World Politics and the Treaty of Versailles (1919–1922)

- XXXVI World Politics and the Treaty of St. Germain (1919–1922)

- XXXVII World Politics and the Treaty of Trianon (1919–1922)

- XXXVIII World Politics and the Treaty of Neuilly (1919–1922)

- XXXIX World Politics and the Treaty of Sèvres (1919–1922)

- XL The Reëstablishment of Peace Prevented by Unsatisfied Nationalist Aspirations and Divergent Policies of the Victors (1918–1922)

- XLI The Russian Revolution and its Aftermath (1917–1922)

- XLII Overseas Possessions of “Secondary States” (1815–1922)

- XLIII French Colonial Problems (1901–1922)

- XLIV British Imperial Problems (1903–1922)

- XLV The Foreign Policy of Post-Bellum Japan (1919–1922)

- XLVI The Place of the United States in the World (1920–1922)

- XLVII Bases of Solidarity Among English-Speaking Nations (1922)

- XLVIII The Continuation Conferences: From London to Genoa (1919–1922)

- XLIX The Washington Conference and the Limitation of Armaments (1921–1922)

- Bibliography

- Index