![]()

Part I The Historical Foundations of Soviet Psychology

The defining characteristics of Soviet psychology are placed in a historical context in terms of the emergence and evolution of a number of basic principles generated in the course of the evolution of Russian social and political institutions.

In this section, a concise summary of this development is provided. An attempt is made to pinpoint the specific differences between the origins of psychology in Russia and parallel, but relatively earlier, movements in West European thought.

The significance of the views of Lomonosov, Radishchev, Belinsky, Chernishevski, and other thinkers discussed in this part will become clear in the light of later developments. In turn, these earlier views will throw light on the later Soviet developments and the controversies about scientific method in the analysis of human behaviour.

Soviet psychology originated and developed within a context of continuing social and political controversies. Its general theoretical principles emerged from a head-on collision between revolutionary, extremist ideas and an entrenched, ultra-conservative set of dogmas about human nature, about the social environment, and about the possibility of change.

![]()

Chapter 1 Social and Political Context

The origins of scientific psychology can be understood only in the context of social and political developments. Russian society under the Autocrat is almost a perfect example of social equilibrium. Tsarism, as a form of government, was the integral product of evolution within, and diffusion across, a territory of vast expanse, inhabited by millions of illiterate peasants, capable of only a low level of agricultural technique. A type of oriental despotism fitted the objective needs of this situation for long periods, at least as far as the vast bulk of the population was concerned. Had it been possible for the Russian Empire to remain an autarchy, isolated from all other human society, its characteristic institutions – autocratic government; Orthodox religion accepted by, or imposed on, all citizens; serfdom for the great majority; and a bureaucratic routine which maintained the administrative machine as a going concern – could have persisted until the last judgement. But this could not be. A succession of ‘Westernizers’ – the first being a reigning Tsar, Peter I – opened up avenues for the diffusion of external, exotic materials and productive processes, innovations in government and religion, aspirations towards a different way of life. Among these exotic materials were ideas about what constitutes ‘the good life’ and about human nature in general.

(i) The Social Background: Narodnost’

A discussion of centuries-long standing continues inside and outside the Russian lands. The question is whether these territories, and the peoples who inhabit them, have a special history and destiny or whether they belong to Europe by virtue of common origins and a shared culture. Geographically, the Urals divided the Empire of the Tsars (and now the Soviet Union) into one portion designated ‘European Russia’, and another designated ‘Asiatic Russia’. But the fact is that the schism which tore apart the Christian Church in the eleventh century is of considerably more importance: it gave rise to two distinct ecclesiastical and social cultures which evolved without much interrelation for many centuries. It is true, of course, that the schism itself was a recognition of basic differences which ran deeper than religion.

At a later period, Russia survived the Mongol invasion, only to be subjected to another form of oriental despotism (Tsarism), which survived into the twentieth century. Long after other European nations had abandoned medieval forms of economic and social organization, a retrograde system of military feudalism survived, with the vast majority living as serfs, operating a stagnant economic system. The mass of the population was illiterate and subject to a reactionary Church, which strongly supported other Departments of State in persecuting unorthodox opinions – these including any expression of a modern viewpoint.

Lenin, in his study of the development of capitalism in Russia, points to an essential difference between the Russian system of ‘natural’ economy and West European capitalism:

The law of pre-capitalist modes of production is the repetition of the process on the previous scale, on the previous basis…. Under the old modes of production, economic units could exist for centuries without undergoing any change either in character or in size…. Capitalist enterprise, on the contrary, inevitably outgrows the bounds of the village community, the local market, the region, and then the State.1

The relentless and all-powerful influences of custom, the dominant role of conservative social forces like religion, the patriarchal and extended family, the unanimity principle in village government, the communal land relationships and arrangements, the absence of a literate population – these characteristics of Russia under the Tsars all bear the hallmark of the static mode of production referred to by Lenin. Any variation in the seasonal routine carries with it the possibility of a dangerous, perhaps total, breakdown in the process of production, on which survival depends. Likewise, any variation in the thought and behaviour-pattern of the individual is believed to endanger the whole community. It is clear that the economic self-sufficiency of the village, based on the ‘natural’ system of economy, with its repetitious cycles and the dependence of each subsystem on the proper functioning of the total apparatus of production, is directly related to the subordination of the individual to the family, to the community, and to the State. The ideology of peasant society reflects in detail the static mode of production: it is a kind of analogue model. This is because it is a product of, and, at the same time, a strong support of the prevailing social and economic relationships and systems.

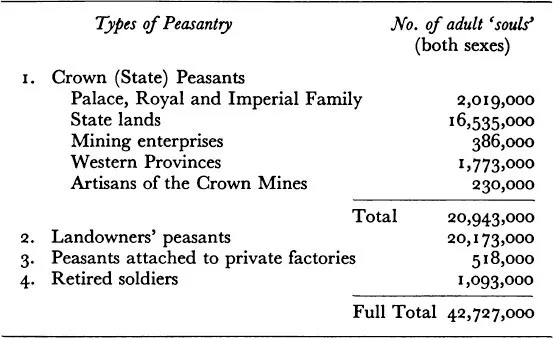

According to the Russian Imperial Census of 1858, the rural population consisted of 51,516,000 adults. The majority of these were serfs; only about nine million being free peasants. The serf population could be classified as shown in the following table:2

TABLE 1. Classification of the Russian Serf Population, 1858

It is clear from these figures that Tsardom was a principal beneficiary and the main support of this system of human enslavement. The landlords, of whom there were 30,000, controlled the lives and destinies of over forty million serfs, settled on twenty million desyatins of land. The ownership of the land was a matter of dispute between the ideologists of the peasantry and the landlords. The peasant theory was that while the landlords owned the peasants, the peasant owned the land. In actual fact, the land was largely mortgaged to the banks, the landlords having contracted a debt of 395 million roubles, more than 53 per cent of the total value of the land.

As far as cultivation was concerned, there was a division into land, which was cultivated by the peasant community, and land cultivated for the landlord in payment for the use of the former. However, in many cases the payment in labour (barshchina) was replaced by a quit-rent (obrok) or money-payment. The amount of labour-time, required from the peasant by the landlord, varied according to the district and the quality of the land. Normally it amounted to two or three days in each working week. The landlords had naturally an interest in increasing their income. This could be done by arbitrarily increasing the amounts of barshchina, or obrok, or by selling their freedom to those serfs who had been able to enrich themselves within the system of serfdom. This they could do by trading on their own account, or by working on contract, or by other means.

Because of the feudal relations between master and serf in the sphere of agricultural production; because of the tribute the landlords exacted from industry in the form of quit-rents paid by their proletarianized peasants, forced to take seasonal town employment to accumulate obrok payments; because of the corrupt bureaucracy and backward-looking aristocracy, the Russian economy remained at a low level. A form of protected capitalism had been introduced by Peter in the shape of State monopolies and subsidized industries necessary for his military enterprises. Foreign capital and investment had been attracted to Russia by a succession of Autocrats, especially French and British capital. But there was no social or economic basis for that ‘constant transformation of the mode of production, the limitless growth of the scale of production’ which Lenin describes as of the essence of capitalism.

The system of taxation, which exempted the great landowners, tended to kill all initiative at the lower levels. The productivity of labour remained low. The population was almost wholly illiterate; the peasantry lacked the basic skills and attitudes necessary for capitalist enterprise. There were certainly changes within the system – for example, the division of labour, which signals and accompanies the breaking-up of the system of natural economy, had been quickened by the Tsarist conquests of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Population changes also occurred. For example, between 1722, when the first census of serfs was taken, and the tenth revision of 1858, the population increased six times. The natural increment in this period was four times; double the original number had been added by conquest. However, about 70 per cent of the Imperial population were serfs of one kind or another; less than 6 per cent of the population lived in towns.

The economic backwardness of Russia dates from the end of the eighteenth century. The political reaction to the French Revolution of 1789, following on Pugachev’s revolt of 1773–75, entrenched the system of serfdom and autocratic government in Russia. One result of this was that English and continental capitalism left Russian capitalism far behind during the nineteenth century in terms of growth and diversification. The centre of capitalist development was Tsarist Poland rather than Russia itself.

Serf agriculture was characterized by a permanent and ineradicable crisis. The landlords’ interest in intensive farming, derived from English developments in this area, disappeared by about 1840. Even after the Emancipation of the Serfs (1861), and in spite of the growth in population and territory, Russian agriculture showed a stationary yield (1801–70), punctuated by crop failures and widespread famines throughout the nineteenth century. The fact seems to be that there was no possibility of establishing a rational system of agricultural production under serfdom since there was no method of establishing the costs of production with any accuracy. Serfdom concealed the existence of agricultural underemployment on a massive scale. Labour productivity was inevitably low, as under any system of slavery: techniques remained at a primitive level. The system of obrok, where the serfs paid rent in lieu of labour-time, had within it the germs of a rational system of capitalism in agriculture. This system gave at least the possibility of a free influx and efflux of labour, a reasonable system of cost-accounting, a basis for credit advances to landlords on a foundation of rational expectations, and a method of primary accumulation necessary for capitalizing farming and industry. But, as late as 1861, 75 per cent of the peasants in the fertile black-earth region (chernozem soils) were still barshchina serfs. This system of cultivation repaid landlord investment many times over. But the system of obrok was typical only of the relatively infertile podsol (or clay soil) regions, where the yield hardly repaid cultivation and where rent provided a stable and profitable source of income to the landowner.

The class groupings in Tsarist society originated on the basis of their position as beneficiaries from, or as unwilling contributors to, the system of serf proprietorship. The social, political, and economic views of the different social classes and strata clearly reflected their class interest in maintaining, modifying, or abolishing the serf system of economy. Each of these social groupings had their own developed views about human nature, about social organization, about their origins and characteristics.

The Autocrat was at once the leader, and the captive, of the largest landowners. Their interest continued to dominate State action even after it became clear that the State itself must perish in the general ruin, if change was not allowed. The bureaucracy and its interests were tied to the survival of the Autocracy and the continuance of serf conditions in society at large. The landowners had a vested interest in expressing, as in a wine-press, the last ounce of rent and profit from the peasant. This income was necessary to maintain the system in being – an important element of the system being a rather vacuous social life in the metropolis and an accustomed standard of luxury in the country.

The Orthodox Church operated as an extension and support of the State system. It was a kind of religious ‘reflection’ of the autocracy and bureaucracy. As far as their social interventions are concerned, Lenin may be quoted to the effect that the priests of the Orthodox Church acted always to safeguard the interests of the oppressing classes. They supported the most conservative State policies, persecuted dissenters and radicals, and fostered anti-semitism. When the need arose the priests acted as unpaid agents of the secret police. If they participated on the side of reform, it was as agents provocateurs (like the notorious Father Gapon).

The peasants’ economic interest was directly opposed to that of the landlords. It was their purpose to seek to reduce the amount of barshchina and obrok exacted from them, and to increase the share of the peasant community (the Mir) of the land available for cultivation. Although the peasants themselves were lacking a voice and political knowledge, there were many who set themselves up as self-appointed spokesmen for their interests.

The intellectuals had no direct stake in the economic system, nor any recognized function or place in the social system. The Russian word ‘raznochintzi’ refers to them as falling ‘between the social ranks’, that is, as ‘classless’. They tended to group themselves all along the length of the political spectrum. As individuals, they were ready to place their talents at the service of whichever class interest they could make their own, without doing permanent damage to their moral convictions or ideals.

The merchants were interested in supporting the prevailing autocratic and theocratic system but only in so far as it facilitated their activities in the social and economic spheres. Their inclination was to adapt the system in diverse ways, so as to make possible an extension of their financial operations. In general, they were liberals in their social and political views.

The industrial workers had no independent voice or political influence until the late 70s or 80s. Their interests were largely identical with those of the peasants. To this class they remained attached, physically as well as psychologically, until a late stage in industrial development.

These class divisions constituted the social, political, and economic context within which elaborate theories about psychological processes and functions were developed. As the social classes themselves were, in general, hostile to each other, so their elaborated views about the realities of individual and social psychology were also in violent opposition to each other. The main confrontation was between the conservative, religious, Orthodox, theologically based concepts on the one hand, and the radical, secularist, science-based theories of the progressive intelligentsia on the other hand.

(ii) The Ideology of Conservatism under the Tsars: Autocracy

The policy towards education serves as an index pointing to the reactionary nature of those called to rule the Russian State. The official view, reflected in State action during the greater part of the Tsarist period, was expressed by Shishkov when fourth Minister of Popular Enlightenment. He said in the presence, and with the approval, of the Tsar, ‘Knowledge is of value only when like salt, it is used and offered in small quantities in accordance with the people’s circumstances and needs … To teach the mass of the people or even the majority to read will bring more harm than good.’3 The Tsar and his advisers were hardly conscious of the fact that they were defending their material interests and specially favoured position. They conceived their task to be something much more important: to prevent the dissolution of society into a jungle where justice would perish, where self-interest would reign unchecked, and where men would give way to every evil influence. These conclusions were the outcome of reflection on a long chain of historical events. The fact that these events were perceived through the prism of dynastic interests, Orthodox religion, and class supremacy was, more or less, apparent to other social groups but not to officialdom. For them ...