![]() Part I

Part I

Intersection family business and entrepreneurship![]()

1

Partitioning socioemotional wealth to stitch together the effectual family enterprise

Saras Sarasvathy, Ishrat Ali, Joern Block, and Eva Lutz

This chapter seeks to bring together two recent and growing literatures – family business and effectuation. The use of effectual logic by expert entrepreneurs has begun to be empirically validated through a series of recent publications (Dew, Read et al., 2009; Read et al., 2009; Sarasvathy & Venkataraman, 2011; Wiltbank et al., 2009). In light of this consider the scope of family business – for example, Miller and Miller (2005) estimates that between one- and two-thirds of public companies around the world are family controlled and over three-fourths of all jobs in the US are created by them (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 1999; Villalonga & Amit, 2010). Yet, little work has been done on the use of effectual logic by family firms.

To kick start future research at the intersection of family business and entrepreneurial expertise, we begin by summarizing what we have learned empirically about each of them as separate streams of literature. Thereafter we examine the implications of the empirical results for theoretical overlaps and finally push forward with an integrated theoretical specification for future research in this space.

Whereas our first instinct was to seek to analyze the variance between family and nonfamily firms in their use of effectual logic, a deeper examination of both extant literatures suggested a pair of more nuanced approaches. These approaches are also very much in line with how the two separate literatures have been evolving. First, in the case of family firms, although early work focused on patterns of variation between family and nonfamily firms (Anderson & Reeb, 2003, 2004; Dyer & Whetten, 2006; Gallo, Tapies, & Cappuyns, 2004; Harris, Martinez, & Ward, 1994; Lee & Rogoff, 1996), more recently, heterogeneity within family firms has emerged as an interesting phenomenon in itself (Bammens, Voordeckers, & Van Gils, 2008; Chrisman et al., 2007; Dawson, 2011; Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003b; Schulze et al., 2001; Westhead & Howorth, 2007). Second, attempts to measure the use of effectual logic by average (as opposed to expert) entrepreneurs have shown that effectuation may be a formative construct better studied at the level of individual principles and heuristics than as a reflective uni-dimensional one (Chandler et al., 2011). Therefore, in our theoretical specification, we construct propositions around the differential use of individual effectual principles within family firms. This twin focus on the relationship between the deconstruction of effectuation and heterogeneity within the population of family enterprises led us to an unexpected insight. In particular, it led us to undertake a theoretically meaningful partitioning of a construct that has become increasingly important and central to the study of family business – namely, socioemotional wealth (Berrone et al., 2010; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). We separate socioemotional wealth into factors that are focused on and driven by the need for family control and those that result in stewardship behavior toward both family and nonfamily stakeholders. We propose that the former hinder the use of effectual logic, whereas the latter enable and should facilitate it.

The chapter is structured as follows. A brief introduction to effectuation including a summary of recently published work in the area is followed by a more detailed review of the empirical literature on family business, which we then organize, interpret, and analyze in terms of facilitating or hindering the use of individual effectual principles. The propositions arising out of this analysis highlight a contradiction – on the one hand, a major barrier in family firms to the use of the crazy quilt principle and, on the other, a natural facilitation of the same. Consequently, we conclude the chapter outlining the need to partition the notion of socioemotional wealth into issues of family-centered and other-centered components.

A brief introduction to effectuation research

Effectuation is a collection of heuristics induced from a cognitive science based study of expert entrepreneurs. The heuristics are internally consistent and hence form a useful logic that is practically and pedagogically relevant as well. Drawing on well-established rigorous methodology from the field of cognitive expertise (Ericsson & Simon, 1993), the original study developed and used a representative sample of expert entrepreneurs who were asked to think aloud continuously as they solved the exact same set of typical decisions that need to be made in starting new ventures. “Expert” was defined as someone with ten or more years of experience founding multiple ventures including successes and failures with at least one company taken public. Expertise, therefore, is not the same as success (as it includes both successes and failures and every other type of experience involved in a long career in entrepreneurship), yet it is more than experience alone (for it includes considerable proof of superior performance). And the fact that the sample was deliberately varied widely in terms of the industries in which the entrepreneurs had founded firms ensured the likelihood that the protocols extracted would embody “entrepreneurial” as opposed to technical or other types of expertise.

Once the key principles and heuristics involved in effectuation were extracted from the expert entrepreneurs, the original study was directly replicated with novices and corporate managers (Dew, Read et al., 2009; Read et al., 2009). Thereafter, some of the key principles and heuristics were incorporated into other methodological instruments such as a scenario-based survey, a conjoint experiment and meta-analytical constructs with a view to using a multi-method approach to cumulating evidence (Read, Song, & Smit, 2009; Wiltbank et al., 2009).

These were concurrently supplemented with a collection of in-depth case studies and histories as well as new quantitative and qualitative metrics and measures. For example, Brettel et al. (2011) have documented its use in R&D and Fischer and Reuber (2011) have shown how entrepreneurs effectuate using social media. Attempts at developing better measures are also under way (Chandler et al., 2011). The research stream appears to be moving beyond evidencing the use of effectuation toward fleshing out the principles in greater depth (Dew, Sarasvathy et al., 2009; Dew, 2009; Dew, Sarasvathy, & Venkataraman, 2004) and constructing connections to other intellectual streams such as Austrian economics (Chiles, Bluedorn, & Gupta, 2007; Chiles, Gupta, & Bluedorn, 2008; Sarasvathy & Dew, 2008; Sarasvathy & Venkataraman, 2011), evolutionary economics (Endres & Woods, 2010), entrepreneurship education (Harmeling, Sarasvathy, & Freeman, 2009), trust (Goel & Karri, 2006), and resilience (Hayward et al., 2009).

In the following three-part outline of what we know about effectuation so far, we begin with the overall process, then list and explain the five specific principles, and end with a brief look at what these imply about human behavior in general and business creation, management, and performance in particular.

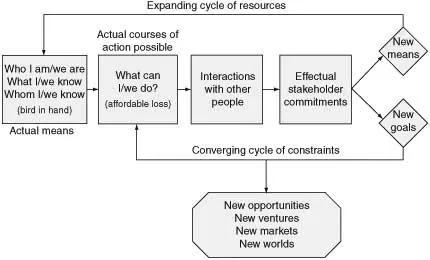

Elements of the effectual process

Expert entrepreneurs begin with who they are, what they know, and whom they know, and immediately start taking action and interacting with other people. They focus on what they can do and do it, without worrying much about what they ought to do. Some of the people they interact with self-select into the process by making commitments to the venture. Each commitment results in new means and new goals for the venture. Note that it is not preset goals that lead to targeted stakeholder selection. Instead, people self-select into the process – and the commitments they may make specify their role and help co-create the goals and vision on the venture and its environment. As resources accumulate in the growing network, constraints begin to accrete. The constraints reduce possible changes in future goals and restrict who may or may not be admitted into the stakeholder network. Assuming the stakeholder accumulation process does not prematurely abort, goals and network concurrently converge into artifacts that may include not only new ventures but also new products, services, markets, opportunities, institutions, and other possibilities.

The process is graphically represented in Figure 1.1 and explicated in greater detail in Sarasvathy and Dew (2005). The process diagram also illustrates how the principles listed below iterate and dynamically drive the process over time.

Five principles of effectuation

At each step of the effectual process, expert entrepreneurs use the following principles, each of which allows them to shape and co-create the venture and its environment without having to predict the future. In short, most conventional approaches to decision making involve trying to predict better. For conceptual clarity we group these predictive approaches under the rubric “causal” – to theoretically contrast it with what expert entrepreneurs do using an “effectual” logic. In the brief descriptions of each effectual principle below, notice the contrasting causal inversion to the same decision problems.

The bird-in-hand principle

This is a principle of means-driven (as opposed to goal-driven) action. The emphasis here is on creating something new with existing means than discovering new ways to achieve given goals. This principle partially overlaps with the notion of bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Whereas bricolage is focused on means-driven strategies as well, bricolage does not require decision makers to be untethered to goals as the bird-in-hand principle does (Baker, Miner, & Eesley, 2003).

Figure 1.1 The stakeholder self-selection process (the dynamics of the crazy quilt principle).

The affordable loss principle

This principle prescribes committing in advance to what one is willing to lose rather than investing in calculations about expected returns to the project. While affordable loss can be used as part of a net present value analysis as well as a real options analysis, effectual entrepreneurs tend to use it without trying to accurately predict the upside (Dew, Sarasvathy et al., 2009). In other words, the emphasis here is to control the downside and seek out non-economic upsides that are worthwhile even if the financial investment is completely lost.

The crazy quilt principle

This principle involves negotiating with any and all stakeholders who are willing to make actual commitments to the project, without worrying about opportunity costs, or carrying out elaborate competitive analyses. Furthermore, who comes on board and what they commit shapes the goals of the enterprise and the roles that they play. Not vice versa. This principle is at the heart of the dynamics of effectual entrepreneurship as we will see throughout the rest of this manuscript.

The lemonade principle

This principle suggests acknowledging and appropriating contingency by leveraging surprises rather than trying to avoid them, overcome them, or adapt to them (Dew, 2009). Conventional wisdom advocates starting with clear goals, making accurate predictions, careful plans, and then, of course, avoiding surprises to the extent possible. Effectuation advocates openness to surprises and a creative stance toward even unpleasant surprises with a view to transforming them into useful inputs into the effectual process.

The pilot-in-the-plane principle

This principle urges relying on and working with human agency as the prime driver of opportunity rather than limiting entrepreneurial efforts to exploiting exogenous factors such as technological trajectories and socio-economic trends. It also acknowledges and embraces the pragmatist view that William James stated with characteristic eloquence: “The trail of the human serpent is thus over everything.” (James, 1948).

In sum, each of the five principles above embodies techniques of non-predictive control – i.e., reducing the use of predictive strategies to control uncertain situations – rather than trying to predict the future more accurately in the hope of being one step ahead of others in exploiting it. The overall worldview of the effectual entrepreneur is one of making, as well as finding opportunities and advantages, co-creating the future with self-selected stakeholders, as well as executing on pre-commitments from them in conjunction with one’s own aspirations and goals.

Effectuation is the inverse of causation. Causal models begin with an effect to be created. They seek either to select between means to achieve those effects or to create new means to achieve pre-selected ends. Effectual models, in contrast, begin with given means and seek to create new ends using non-predictive strategies. In addition to altering conventional relationships between means and ends and between prediction and control, effectuation rearranges many other traditional relationships such as those between organism and environment, par...