![]() Part 1: Framework

Part 1: Framework![]()

Vernacular architecture: A paradigm of the local seismic culture

F. Ferrigni

European University Centre for Cultural Heritage, Ravello, Italy

ABSTRACT: After the Irpinia 1980 Italian earthquake, it turned out that the usual tools of the seismic engineers were not useful enough to analyse the historical retrofitting, following the seismic shocks. In these buildings, damages were mainly caused by the lack of or bad maintenance.

In 1985, the European University Centre for Cultural Heritage launched a research, to assess the traditional seismic-proof techniques existing around the world. This made it possible, to define the mastery of these retrofitting techniques, and the consistent behaviour of ‘Local Seismic Culture’ (LSC). This paper deals with the different kinds of LSC, depending on the intensity/recurrence of earthquakes, which shows the effectiveness of traditional techniques against all components of seismic shocks. It also proposes an introductory tutorial, to recognise LSC elements in vernacular architecture.

1 INTRODUCTION

On the 23rd of November 1980, a 6.5 Maw earthquake hit the Irpinia region, in Italy, heavily damaging more than 120 historical centres. During the following years, the protection of historical built-up areas began to focus on scientific and political debates. At the time, the methods to calculate/check masonry structures were rough: POR Method, based on a very simplified model of isolated buildings, was unusable for the connected and irregular historical built-up areas. The evolution to FEM (Finite Elements Method) offered, to seismic engineers, more precision in structural calculation of buildings having irregular geometry; but the difficulty in knowing the exact kind of materials in each point of structures, made it difficult to apply the FEMs to the historical built-up.

Nevertheless, there was evidence of a fact: despite all numerical simulations show that the majority of historical buildings had collapsed, they were, in fact, standing. On the other hand, it is easy to recognize, in regions where the seism is recurrent, that local communities necessarily had to develop “seismic-proof” construction techniques. So, when trying to answer the question “what is it necessary to do, to protect the historical built-up areas?” a new question emerges: “what have builders/users of historical built-up environment done, to protect it against the seismic shocks in seismic prone regions?”

Moving from this question, in the frame of EUROPA (Eur-Opa Major Hazards Agreement, a Program of the Council of Europe), in 1983 the European University Centre for Cultural Heritage (EUCCH) of Ravello launched a research line on traditional seismic-proof technologies around the world. The desk analysis showed many ancient methods used to dissipate the energy generated by seismic tremors in monuments: Greek temples (Touliatos, 1994), ancient pagodas in China (Shiping, 1991), or Japan (Tanabashi, 1960). Field researches carried out in Italy, Greece and France added more examples of traditional seismic-proof techniques in vernacular architecture (Helly, 2005). At the same time, researches on Naples’ historical built-up area, carried out after the 1980 Irpinia EQ, showed that the extent of the observed damage was more closely correlated with the population density, than with the age of the buildings, and with their materials (De Meo, 1983). In other words, the correct use, and the appropriate maintenance of buildings resulted, at least as important, as the performance of the structures.

At the end of the research, all traditional seismic-proof techniques both common in monuments, and in vernacular architecture –, as well as the use of the buildings have been considered the result of a “Local Seismic Culture” (LSC), defined as the “combination of knowledge on seismic impacts on buildings and behaviours in their use, and retrofitting consistent with such knowledge” (Ferrigni, 1985).

During the following years the LSC research line has been focused on retrofitting of vernacular architecture in seismic regions, by means of a series of intensive courses organised on “Reducing vulnerability of historical built-up areas by recovering the Local Seismic Culture”. The aim of the courses was to make aware architects and engineers that “reinforcing” historical buildings, using materials and techniques different than the original ones may be dangerous, as well as to supply them with sample criteria to recognise the seismic-proof elements in vernacular architecture.

The history of the research on LSC around the world; the complete analysis of seismic-proof features of monuments and vernacular architecture in seismic prone regions; the systematisation of different kinds of LSC, depending on recurrence/intensity of earthquakes; and the usefulness of a LSC approach in retrofitting historical built-up, have been published in “Ancient buildings and Earthquakes” (Ferrigni et al., 2005).

2 THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF LSC

In ancient societies, knowledge was handed down by word of mouth, from master to apprentice. The assumption for a technique to be validated and the relevant know-how to become firmly established was that one, and the same generation should be in a position to analyse the damage caused by an earthquake, define new construction techniques, or carry out repairs, test them during the next earthquake and hand down its own conclusions to the next generation.

However, if the time lag is very long (one century or more), empirical knowledge is most unlikely to take root. In practice, there is evidence that a community will be able to develop empirical know-how concerning the most effective construction techniques, only if the interval between two successive earthquakes does not exceed 40–50 years. Although specific construction techniques may be well-established locally, a generation, which has never experienced an earthquake, will not really develop an awareness of the seismic-proof function of given features, comparable to that, which induced the previous generations to adopt them. It can be assumed that the observation of the different impact of a new earthquake on different buildings will generate new awareness and rekindle knowledge, which had been forgotten. This will determine, after an earthquake (EQ), a sudden increase in the level of knowledge, and a corresponding expansion of the LSC. Subsequently, the physiological tendency towards repressing the memory of that event will result in the loss of the knowledge acquired, and the resulting culture may even be more fragmentary than it was before the tremor occurred (Fig. 1a).

On the contrary, if the earthquakes follow upon one another, at intervals of time, which enable a generation to hand, their experience down to the next generation by word of mouth (40–60 years), the local seismic culture will be embedded.

Provided these assumptions are met, the effectiveness of building techniques can be tested in a sufficiently frequent and reliable way, and the criteria adopted in building and repairing buildings can become the common heritage of a community (Fig. 1b)

But the degree to which empirical knowledge takes root does not only depend on the frequency of seismic events. The damage caused by small-scale tremors, albeit frequent, will not be severe enough to allow people to select the most effective techniques. Nor will the impact of exceptionally severe earthquakes. If all the buildings are destroyed, it will be difficult to assess the comparative effectiveness of different technical devices. Not to mention the fact that a catastrophic earthquake wipes out the very memory of techniques previously in use, because it destroys existing documents, and causes people’s death, who were conversant with their contents.

Figure 1. If the recurrence of EQ is low (a), the experience of a generation can’t be transmitted to the next one. In regions having a high recurrence (b) the “seismic-proof” knowhow stay, an LSC can root (credits: Ferruccio Ferrigni).

According to the MCS scale for classifying earthquakes, the intensity of an earthquake is generally based on the type of damage observed in the buildings that are affected. Major cracks and fractures which, though sizable, do not jeopardise the stability of the buildings, are classified between intensity II and V. An earthquake of intensity VI or VII produces more serious cracks, but only a small section of the buildings collapse in part, or suffers from damage to the point where they become unstable. An earthquake, which shakes the outer walls of a large number of buildings (causing the walls to come apart at the corners) is classified as intensity VIII. Situations where buildings actually collapse are typical of intensity IX. An earthquake of intensity X causes extreme damage to all buildings, besides numerous building failures. Intensify XI results in the near total destruction of the built-up area, including constructions such as bridges and dams, as well as cracks in the ground.

With close approximation it is possible to assume, therefore, that a LSC will only emerge as a result of severe, but not catastrophic earthquakes. In practice, earthquakes between intensity VII and X, on the MCS scale.

In conclusion, only earthquakes, which follow upon one another at suitable time lags, and with an ‘appropriate’ recurrence/intensity combination, are likely to result in a sound LSC. This observation implies two highly interesting consequences for the LSC approach. If the intensity/recurrence rates of earthquakes experienced in different parts of a country or region in a diagram is reported, it is possible to identify the areas where it is most likely to find traces of an LSC. In addition to this, it is also possible to tell, in advance, if the LSC of a given place is a set of construction ‘techniques’ in use, regardless of the occurrence of any earthquakes; or if it has established itself in the wake of an earthquake, based on the carried out ‘retrofitting’ actions (though a combination of these is also possible).

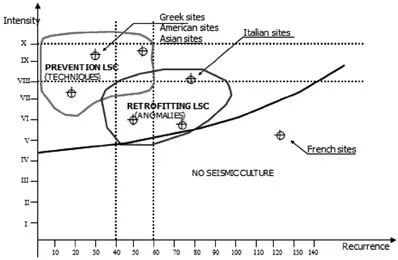

The Fig. 2 shows the position of the case studies analysed by EUCCH’s field research, in a EQs recurrence/intensity diagram. In the diagram the ‘optimal’ range of recurrence and intensity, facilitating the rooting of an LSC is marked. Starting from this, it is possible to identify different ‘LSC domains’:

• Places with a high recurrence of major earthquakes: memory of the effects of the earthquakes remains alive. Buildings invariably show a number of built-in features, which make them more earthquake-resistant (and the ‘seismic-proof techniques’ that are observed there will point to what it may be called a ‘prevention LSC’);

• Places exposed to medium/high intensity, but not frequent, earthquakes: memory of their effects fades as time passes. Another earthquake causes damage; the buildings must be reinforced haphazardly, by adding new structures or mending the existing ones (in this case the LSC concerned is said to be ‘retrofitting-oriented’, and it is revealed by the ‘anomalies’ recognised in the buildings).

• Places comprised within the part of the diagram, in which earthquakes are less frequent and/or of lesser intensity: here any traces of a LSC will be hardly found.

• In addition, there are places where earthquakes, though rare, occur with catastrophic intensities. Here, too, it is unlikely to find a well-rooted or generally recognised LSC, while it is highly probable that entire cities had to be relocated, and the new ones reconstructed according to imported and/or imposed technical criteria (in these cases it might even be spoken of an ‘imposed by decree LSC’).

Figure 2. By locating a specific site in a Recurrence/Intensity diagram one can find out in advance if there is a reasonable probability of finding evidence of LSC and, if so, what type is it (prevention/retrofitting LSC) (credits: Ferruccio Ferrigni).

3 THE LSC: A COMPLETE RESPONSE TO THE SEISMIC SHOCK

Leaving aside the specific parameters of each earthquake (magnitude, frequency, duration, ground motion, etc.), and generally speaking, it might be said that the forces that act on buildings during an earthquake are of three kinds: vertical, horizontal and torsional. In mechanical terms this means that a seismic shock suddenly increases the vertical load on bearing and horizontal structures, while generating shearing stress at the base of buildings, as well as a twisting motion of their vertical edges.

It is true to say that man-made artefacts are designed to resist gravity, but these...