![]()

1

The Lives and Lifestyles of Ancient Hunter–Gatherers: “Poor, nasty, brutish and short” in the American Great Basin?

FOR ALL but the last ten thousand years or so, our species has depended solely on wild plants and animals for food. In some regions of the world, this lifestyle continued until very recent times. In the American Great Basin, a vast region encompassing much of the western United States—including most of Nevada and parts of Utah, California, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming—native peoples have always lived exclusively on wild plants and animals, at least until relatively recent times. The study of the skeletal remains of these natives—viewed in the context of environment and culture—offers us insight into the quality of life that is associated with hunting and gathering. In this chapter, we look at what the study of skeletons of early hunter-gatherers can tell us about our past.

I began thinking about ancient foragers long before I began to look at archaeological skeletons from the Great Basin. In the summer of 1973 I was fortunate to participate in the National Science Foundation’s Undergraduate Research Participation (URP) program, having been selected to work with David Hurst Thomas of the American Museum of Natural History on archaeological excavations that he was directing at Gatecliff Shelter, Nevada. Gatecliff is a deeply stratified archaeological site located in the desert of central Nevada, the heart of the American Great Basin. In fact, it is one of the most deeply stratified sites in the Western Hemisphere. I was thrilled to be able to gain experience in an area of the world that I knew nothing about, and at such an important archaeological site. The summer before, I had worked with Smithsonian Institution physical anthropologist Douglas Ubelaker as an URP summer intern in his excavations of skeletons from a late prehistoric ossuary in southern Maryland and in follow-up laboratory analysis. Although I could have continued to work solely on bones, I decided that it was more important at this early stage of my education to see a wide range of archaeological settings, especially before making decisions about how I would focus my graduate studies that would be coming up in a couple of years. Prehistoric Indians used Gatecliff mostly as a living site, and it contained none of their skeletal remains. However, I knew that my experience doing archaeology at the site would give me new and valuable perspective on the ancient past. I was not to be disappointed. Although arduous—the desert is not an especially hospitable place, and the labor was intensive at times—the work in Nevada that summer was terribly interesting and exciting.

Thomas was keenly interested in the prehistoric settlement systems and lifestyles of the Great Basin Shoshone Indians. His work showed that the prehistoric Shoshoneans who lived in the Reese River valley of central Nevada moved about the landscape according to the season of the year and availability of wild foods. The seasonal round involved harvesting nuts from forests of piñon pine (Pinus monophylla) trees in the mountains in the autumn. Piñon pine nuts were a highly nutritious food staple for Great Basin Indians; these nuts are high in fat, carbohydrates, and protein, and they sustained the local populations through the long winter months. During the winter, people moved very little from their upland homes. Once Indian rice grass (Oryzopsis hymenoides) ripened in the summer, small bands of foragers moved out of their mountain communities onto the valley floors for the summer harvest. Because the food sources on the valley floors were scattered in isolated patches, the summer camps moved frequently from one location to another. The eminent cultural anthropologist Julian Steward identified this pattern of resource exploitation and seasonal mobility in Indians living in the area in the 1930s. Forty years later, Thomas’s innovative research confirmed the pattern, and he suggested that this way of life had lasted for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

In working with Thomas at Gatecliff, I began to ponder the questions and issues raised by archaeologists interested in human adaptation. I asked myself, could the study of skeletal remains of these ancient populations inform our understanding of prehistoric lifestyles in the Great Basin? Thomas’s research was compelling, but wouldn’t it also be important to increase the comprehensiveness of the research and tie in the special knowledge gained by the study of ancient skeletons? As a lowly undergraduate working with a team of seasoned archaeologists, I kept these thoughts to myself until such time that I could contribute substantively to the ongoing discussion of prehistoric Great Basin lifestyles.

From my training in physical anthropology, I began to think a lot about variation in lifestyles and adaptation in prehistoric Great Basin (and other) people. Thomas’s work suggested that the prehistoric Shoshone were highly mobile foragers, taking advantage of a wealth of nondomesticated plant and animal resources in different ecological settings. Archaeologist Robert Heizer and his students at the University of California at Berkeley had been studying prehistoric Indians from farther to the west in the Great Basin, having excavated such famous sites as Lovelock Cave and surrounding sites in the Humboldt Sink. Contrary to Thomas’s model of Great Basin adaptation, Heizer contended that native peoples relied on resources associated with permanent and semipermanent Pleistocene-remnant lakes of western Nevada (the lakes had long since disappeared in the central Great Basin). He believed that these populations lived fairly good lives, with plenty of plants and animals that lived along the margins of these lakes and associated wetlands. In contrast to the settlement pattern in central Nevada, native peoples in the Humboldt Sink region were apparently sedentary, with little individual or group movement— the lakes and their shores offered just about all anyone would need for a productive, if not healthy, existence.

After defending my doctoral dissertation at the University of Michigan in the summer of 1980, Thomas invited me to fly out to Nevada from Ann Arbor to see new excavations that he was conducting at a key western Great Basin site known as Hidden Cave, located almost within view of Heizer’s research area in the Humboldt Sink. Overlooking the wide expanse of the Carson Sink, the site provides some tantalizing clues about Great Basin adaptation and lifestyle. Along with skeletal remains found by the earlier archaeologists excavating in the cave, Thomas’s crews had found several dozen fragmentary bones and teeth that he wanted me to study.

HIDDEN CAVE: HINTS AT HEALTH AND LIFESTYLE

Hidden Cave had apparently functioned for storage of tools and other essentials—a so-called cache site—used by a group of native peoples known in historic times as the Toedökadö (translated, “Cattail eaters”), a local band of Northern Paiute Indians. The presence of the skeletal remains in the cave was puzzling, especially since they didn’t appear to be from a formal burial context— all the skeletal elements were separate and disarticulated. Regardless of the context of the human remains, the discovery of bones and teeth refueled my earlier interest in addressing issues relating to prehistoric biocultural adaptation in the Great Basin. For the remainder of the summer, I studied the bones and teeth from Hidden Cave.

In particular, I looked at three indicators in teeth and bones that are highly informative about the quality of life: hypoplasias, porotic hyperostosis, and infection. Hypoplasias are grooves, lines, or pits in the teeth that reflect periods of time when, due to either poor nutrition or disease (or some combination thereof), the outer covering of the tooth—the enamel—stops or slows in its growth. The cells that normally create the enamel—called ameloblasts—fail, and the hypoplasia caused by arrested growth results. The teeth that I looked at from Hidden Cave had only a moderate number of hypoplasias.

Maxillary teeth with enamel hypoplasias (horizontal grooves) on incompletely erupted permanent central incisors. Hypoplasias reflect periods of physiological stress and poor growth. Photograph by Barry Stark; from Larsen 1994, and reproduced with permission of Academic Press, Inc.

I next looked at the skull fragments for evidence of iron deficiency anemia; if this had been present in the population, it would be represented by bone pathology called porotic hyperostosis or cribra orbitalia. These pathological conditions are areas of porous bone in the flat bones of the skull, such as the parietals (porotic hyperostosis) or in the eye orbits (cribra orbitalia). They are created when red blood cell production increases, causing the bone to become porous. The increase in red blood cell production occurs when iron, an element required for the production of red blood cells, is deficient. Red blood cells, among their other functions, are absolutely necessary for transport of oxygen to the various body tissues. Without it, the tissues—and the person—are unable to function properly. Iron depletion occurs either as a result of some deficiency in diet, or chronic diarrhea, blood loss, or in many settings, parasitic infection. A number of parasites—such as hookworm—bleed the human host, resulting in loss of essential iron stores. None of the skull fragments I looked at had pathology reflecting iron deficiency.

Cross-section of mandibular canine showing major parts of the tooth with enamel hypoplasia.

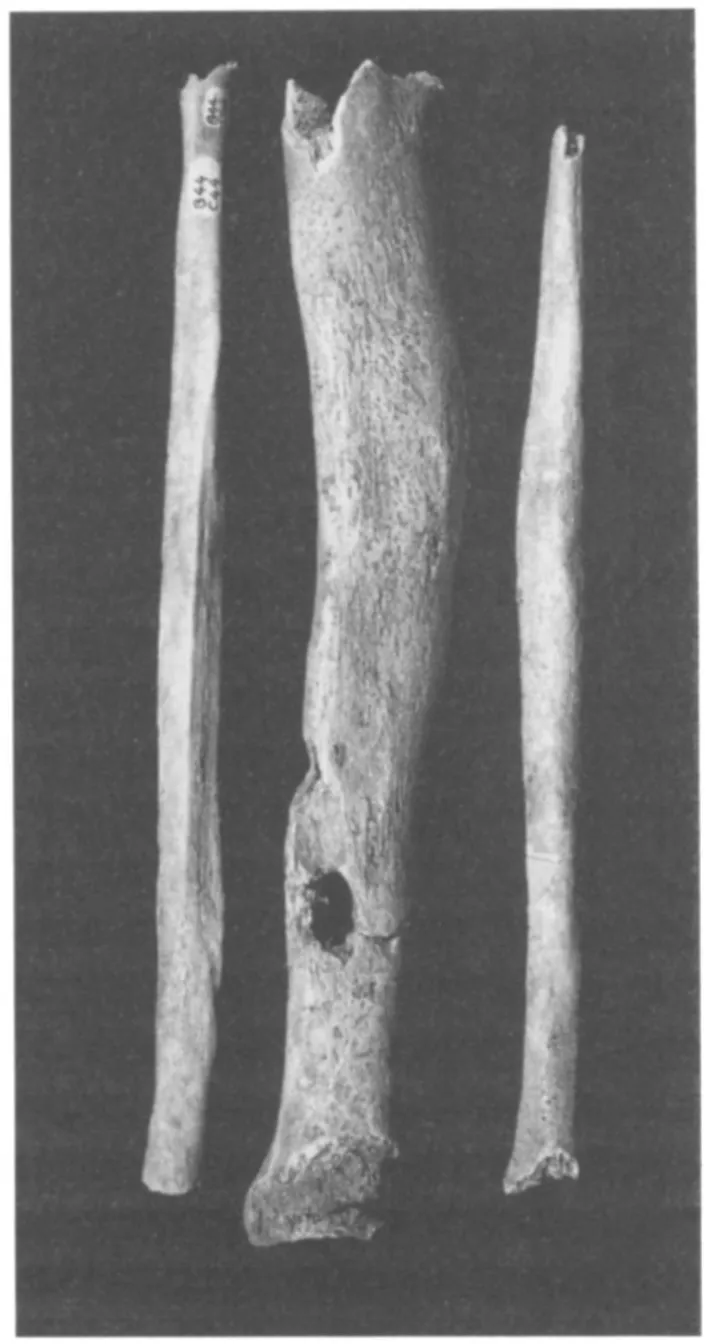

Last, I examined the bone fragments from Hidden Cave for presence of periosteal reactions. These reactions are abnormal growths on the periosteum, the outer surface of bones. Bioarchaeologists and paleopathologists are usually not able to provide a specific diagnosis—what caused the infection—but most are caused by bacterial infections originating from the surrounding soft tissue. Usually, the tibia (lower leg bone) is involved because so little soft tissue separates the skin from the bone. Thus, if there is a cut or abrasion to the skin of the lower leg and an infection involving the skin and soft tissue ensues, the infection can then readily pass to the bone.

Porotic hyperostosis (top) and cribra orbitalia (bottom) in juvenile skulls. These conditions can be caused by iron deficiency anemia. Photographs taken by Mark C. Griffin; bottom photograph from Larsen 1994, and reproduced with permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Adult tibia (middle) and left and right fibulae with periosteal reaction and inflammation, probably due to infection. The large hole in the tibia is caused by drainage of pus. Photograph by Mark C. Griffin.

Periosteal reactions are commonly found in skeletal samples representing populations living in dense, crowded living situations where sanitary conditions may have been poor. My survey of the bone fragments—especially tibia fragments—showed no evidence of periosteal reactions. Thus, based on this limited sample, infection did not seem to be a problem for these early hunter-gatherers.

What was striking about the skulls and teeth of the Hidden Cave people was the sheer size of the faces and jaws, the very large areas of muscle attachment for the chewing muscles, and the high degree of tooth wear and large numbers of chipped teeth. This pattern suggested to me that the masticatory complex was adapted for heavy chewing.1 Lots of chewing demands big jaws, and heavy chewing of gritty, hard foods results in chipping and wear of teeth. Similarly, the postcranial bones, the area of the skeleton below the neck, were large and had big muscle attachment sites, indicating that these people must have led a highly active lifestyle. These were remains of people who didn’t hang out around lake margins enjoying a sedentary lifestyle, which seemed to contradict Heizer’s hypothesis about Great Basin adaptations and was more in line with Thomas’s ideas. Based on this limited sample, I reached the tentative conclusion that the people I studied from Hidden Cave were healthy, but ate tough foods, and were physically active.

Independent of my work, Thomas came to a similar conclusion regarding the activity of these populations: He hypothesized that these people were highly mobile (the limnomobile hypothesis), in contrast to Heizer’s limnosedentary hypothesis, which argued that wetland resources could provide sufficient food and other resources for a hunter-gatherer population. The limnomobile hypothesis argued that, although these wetlands offered plenty to eat and formed a kind of a “hub” of activity in the western Basin, fluctuations in food and other essential resources would have required travel to other areas—sometimes involving great distances. This is not just a local debate of concern only to Great Basin archaeologists. Rather, the debate is couched within the larger problem of the role of the environment in hunter-gatherer adaptations and how archaeologists go about documenting mobility and lifestyle in earlier societies. Unfortunately, I couldn’t say much at the time—my work was based just on the tiny collection from Hidden Cave and it could provide only some very preliminary conclusions.

MORE SKELETONS AND MORE DEAD ENDS

Over the course of the year following the summer’s research at Hidden Cave, I learned just about all there was to know about the bioarchaeology of the western Great Basin—what skeletons had been found, from where, and by whom. I also found the locations of existing collections of skeletons from sites in the Great Basin. From published and unpublished reports and by word of mouth from various archaeologists, I learned that there were many Great Basin remains in the collections at the Lowie (now Phoebe Hearst) Museum of Anthropology at Berkeley and at the Las Vegas campus of the University of Nevada. With a small grant from the American Museum of Natural History, I traveled to Berkeley and Las Vegas, aspiring to study skeletons in order to address unresolved issues about prehistoric native lifestyles in the Great Basin.

After spending about two months collecting data, I developed a fuller picture of the health, lifestyle, and activity levels for native peoples living in the prehistoric western Great Basin. Indeed, this study confirmed my earlier suspicions about health and activity in prehistoric Indians in this region. Based on my documentation of the skeletons, like the ...