![]()

1

DEATH IN POTAMIA

THE VILLAGE OF POTAMIA lies at the edge of a small plain in northern Thessaly, twenty-five miles to the southwest of Mount Olympus. It occupies a triangle of flat land, bounded on two sides by the wide, rocky beds of the Titarisios and one of its tributaries. On the third side rise low hills, rounded, gray, and barren except for outcroppings of scrub oak, which provide meager pasturage for the sheep and goats of the area. In sharp contrast to these stone-covered slopes, fertile land stretches off below the town into the haze of the foothills in the distance. Here lie small rectangular fields of bright green tobacco, yellow wheat, and red, freshly plowed earth. Between the fields stand rows of poplar trees, living fences that mature and grow until they are cut for fuel in the winter.

Irrigation and increased mechanization have brought prosperity to the six hundred inhabitants of Potamia. Their well built two-story houses and bams are surrounded by gray cinder block walls, which divide the town into family courtyards. The one structure that rises above the red brick roof tiles of the village is the bell tower of the church, a nesting site for the storks that return from Africa every spring. Beside the church, near the juncture of the two dry riverbeds, lies the village graveyard. It was here I had come on a hot, cloudless afternoon in July 1979 to learn how the people of rural Greece deal with death.

Upon entering the graveyard of Potamia through an old wooden gate, I was immediately struck by how small it was. Twenty-one graves, set very close together, extended in three rows from the gate to a mass of tangled vines and bushes on the far side. The graves fell into two distinct categories. A few were marked off by a rectangular fence of metal or wood, a cage-like enclosure around bare earth or gravel (Plate 13). At the head of each grave, attached to the grillwork, was a box, sometimes shaped like a house with a peaked roof and a chimney, on top of which stood a cross. Here were kept a photograph of the deceased, an oil lamp, and matches and wicks with which to light it (Plate 16).

Most of the graves were much more elaborate and expensive. White marble slabs, set in cement, formed a raised platform in the center of which was an area covered with gravel, where flowering plants grew. At the head of these graves were marble plaques bearing the name and the dates of birth and death of the deceased. Above the plaques rose marble crosses often decorated with wreaths of plastic flowers. To the right and left of each headstone stood a small box with glass sides and a marble top. One box contained a framed photograph; the other, an oil lamp, a bottle of olive oil, and a jar of dried flower blossoms used as wicks. At the foot of each grave was a large metal container half filled with sand, in which stood the stubs of candles extinguished by the wind (Plates 18 and 20).

As I walked between two rows of graves, I noticed that no grave bore a date of death prior to 1974. The explanation for this, and for the small size of the graveyard as well, lay in a small cement building standing in the corner of the graveyard (Plates 16 and 31). Although I knew what I would find inside, I was still not fully prepared for the sight that confronted me when I opened the door.

Beyond a small floor-space a ladder led down to a dark, musty-smelling area filled with the bones of many generations of villagers. Near the top of the huge pile the remains of each person were bound up separately in a white cloth. Toward the bottom of the pile the bones—skulls, pelvises, ribs, the long bones of countless arms and legs—lay in tangled disarray, having lost all trace of belonging to distinct individuals with the disintegration of the cloth wrappings. Stacked in one corner of the building were metal boxes and small suitcases with names, dates, and photographs identifying the people whose bones lay securely within.

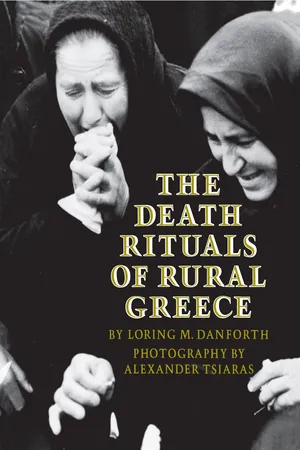

At the sound of the church bell calling the village women to vespers, I went out into the bright sunlight. A few minutes later a woman entered the graveyard, dressed entirely in black, with a black kerchief covering her forehead, hair, and neck (Plate 17). She carried one large white candle and a handful of small yellow ones. After crossing herself three times she lit the white candle and one yellow one at the grave of the person she had come to mourn. Then she went up and down the rows of graves placing candles in the sand-filled containers at the foot of several other graves. Finally she returned to the first grave and began the elaborate procedure of preparing and lighting the oil lamp by the headstone.

Soon the graveyard was alive with activity, and a forest of candles burned at the foot of each grave. About ten women, all dressed in shades of black, brown, or blue, busied themselves lighting lamps and sweeping around the graves. Several women began hauling water in large buckets from the faucet in the church courtyard nearby. After watering the flowers on the graves they were caring for, the women began to wash the marble headstones with sponges and detergent kept in little plastic bags hidden carefully in the grass by the graveyard wall. So attentive was their care for the graves that some women would sift through the sand-filled containers throwing out clumps of melted wax or scrape old wax off the marble slabs with small knives kept just for that purpose.

After fifteen or twenty minutes, when most of this housecleaning had been completed, the atmosphere in the graveyard once again turned somber and quiet. Each woman sat on the grave of her husband, parent, or child, tending the candles and talking quietly with women at nearby graves. They discussed their crops, the weather, or the long-awaited summer visits of their children working far away in Athens, Germany, and the United States. Often their conversations dealt with matters closer at hand—funerals in neighboring villages, the expense of renting a cemetery plot in a large city, or the circumstances surrounding the deaths of their relatives who lay buried beneath them.

One woman sat near the head of a grave, staring at a photograph of a young woman. She rocked gently back and forth, sobbing and crying. Suddenly she began to sing a lament in a pained, almost angry tone of voice. Before she finished the long, melismatic line of the first verse she was joined by other women. The intensity of emotion in the women's voices quickly increased. The verses of the lament, sung in unison by the chorus of mourners, alternated with breaks during which each woman shouted a personal message addressed to her own dead relative.

"Ah! Ah! Ah! My unlucky Eleni."

"Nikos, what pain you have caused us. You poisoned our hearts."

"Kostas, my Kostas, the earth has eaten your beauty and your youth."

These cries were interrupted by the next verse, as the singing resumed. When the first lament ended, a woman sitting in the far corner of the graveyard immediately began a second. Finally, after singing three or four laments lasting perhaps fifteen minutes in all, the women stopped. The loud songs and cries were followed by quiet sobbing and hushed conversations.

Several women stood up, crossed themselves, and announced that it was time to leave. They tried to comfort the women who had shouted the loudest, whose grief seemed to be the most intense, by telling them to have patience, to be strong, and to remember that they accomplished nothing by carrying on so. Two or three of the most grief-stricken women said that they would stay a few more minutes, until the candles burned out; but the other women continued to urge them to leave, saying: "In the end we'll all come here. Even if we sit here all night, the dead still won't return from the grave." After several such exchanges all the women agreed to leave. About an hour after their arrival, they filed out of the graveyard one by one and returned slowly to their homes, to the world of the living.

This sequence of events was repeated daily with only slight variation during my stay in Potamia. I spent my first few evenings at the graveyard standing awkwardly in the corner by the gate, feeling extremely out of place. Several days later my situation became less uncomfortable when Irini, the woman who had begun the lament my first evening in the graveyard, gestured toward the grave on her right and suggested I sit down. That was the beginning of the process by which I came to know these women and to understand the manner in which they experienced death.

The death of Irini's twenty-year-old daughter Eleni was generally acknowledged to have been the most tragic the village of Potamia had experienced in many years. Eleni died almost five years earlier, in August 1974. She had been a very attractive young woman, tall, with long black hair. Since she had been one of the best students in the village elementary school, her parents decided to send her to high school in the city of Elassona, about ten miles away. This involved tremendous sacrifice for her and her family, since at that time there was no regular means of transportation between Potamia and Elassona. As a result, from the age of twelve Eleni lived alone, away from her village, her home, and her family. Several times a week her father would walk to Elassona to bring her food. Since she had done well in high school, Eleni went on to study for two more years in order to become an elementary-school teacher.

One month before she was to begin her first teaching job, Eleni was struck by a car and killed in a hit-and-run accident in the city of Thessaloniki. Several of Eleni's relatives who lived in Thessaloniki were notified of her death by the police. They put on brightly colored clothes and came immediately by taxi to Potamia, having packed black clothes of mourning in their suitcases. When Irini saw them approaching her house, she asked why they had come. They told her that they brought good news and asked her to call her husband and her children, who were working in the fields. When the entire family had gathered, the visitors told them they in fact were bringing bad news: Eleni had been killed. They then changed into their black clothes, placed a photograph of Eleni on the floor in the center of the room, and began the funeral vigil amid wild cries and laments.

The arrival of the body was delayed until the following day because an autopsy had to be performed. When the body finally arrived in Potamia, neighbors and more distant relatives advised burying it right away, but Irini would have no part of it. She wanted her daughter to spend her last night in her family home, which she had been away from for so many years. After a second all-night vigil, Eleni was buried wearing in death the white bridal dress and wedding crown she had been unable to wear in life.

For a full year after her daughter's death, Irini stayed inside her house. She did not want to see people; she did not want to see the light of day. For a full year she did not even go to church, nor did she visit her mother who lived on the other side of the village. The only reason she left her house was to come to the graveyard to be with her daughter. She would come late at night and in midafternoon when other people were sleeping, so that she would not see anyone. Often her husband or her children would come to the graveyard to take her home, but she would return as soon as they left her alone. Eleni's father would also come to his daughter's grave and lament like a woman. He would even sing laments while he was herding his sheep and goats in the hills above the village. People working in the fields heard him and cried.

For the next five years Irini wore black. She never had a chance to put on the red shoes she had bought the week before Eleni's death. Every day without fail for five years she came to her daughter's grave, once in the morning and then again in the evening. She attended all the funerals and memorial services in Potamia and the surrounding villages so she could lament, cry, and express the pain she felt. She knew full well, though, that the wound of a mother never heals, that her pain never ceases. Several years after Eleni's death, Irini's other daughter was married. Irini did not attend the wedding herself, and she refused to allow any singing or dancing in her house on the wedding day. Now, whenever her sonin-law, who lives with Irini and her husband, listens to music on the radio, Irini becomes upset. She says that her heart is poisoned.

Since her daughter's death Irini has become very close to another village woman, Maria. They say they are neighbors in a way, because Maria's son Kostas is buried in the grave next to Eleni. The two bereaved mothers have spent many hours together sitting on their children's graves and sharing each other's pain. Kostas died at age thirty in 1975, just one year after Eleni. He had lived with his wife and young son for several years in Germany, where he worked in a factory. However, because his marriage was unsuccessful, he returned to Greece and found a job as a construction worker in a nearby city. Since his wife, who remained in Germany to continue working, was unable to care for her son, Kostas brought him to Potamia to live with Maria and her husband. Several months later Kostas was killed when the cement frame of the apartment building where he was working collapsed and crushed him. Maria, who blames her daughter-in-law for having made the last few years of her son's life unhappy, is quick to mention that her daughter-in-law did not return from Germany for Kostas' funeral. When she finally did come to the village a year later to visit her son, she was not even dressed in black.

During the many evenings I sat in the graveyard near Maria and Irini I learned much about their encounters with death. Maria would tell Irini how, when no one else is in the house, she takes out some of her son's clothes and hugs them and cries and sings laments. Irini would discuss the dreams that she and her husband had seen prior to Eleni's accident. They now realized that these dreams had clearly foretold their daughter's death. One night Irini had seen her daughter, dressed as a bride, leaving home in a taxi. As all the dream books say, dreams of weddings are ominous signs of impending death. A week before Eleni's death, her father had seen in his sleep a herd of black goats descending the hill toward his pens at the edge of the village.

By mid-July these conversations turned increasingly to the events that would soon cause Maria and Irini renewed grief and pain. At the end of the month Eleni would be exhumed. According to custom this had to be done before she had completed five full years in the ground. She would be exhumed because her family wanted to see her for the last time and because she should not have to bear the weight of the earth on her chest for eternity. She would be exhumed so that she could see once more the light of the sun. During the weeks before the exhumation Irini sang laments more frequently and cried out to her daughter more emotionally:

Eleni, Eleni, you died far from home with no one near you. I've shouted and cried for five years, Eleni, my unlucky one, but you haven't heard me. I don't have the courage to shout any more. Eleni, Eleni, my lost soul. You were a young plant, but they didn't let yo...