Revisiting Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Issues and Challenges in Early Childhood Education

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Revisiting Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Issues and Challenges in Early Childhood Education

About this book

This reflection on Paulo Freire's seminal volume, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, examines the lessons learnt from Freire and their place in contemporary pedagogical theory and practice. Freire's work has inspired ground-breaking research which Vandenbroeck has collated, demonstrating the ongoing influence on early childhood educators.

Vandenbroeck brings together an international cohort of early childhood experts to present cross-cultural perspectives on the impact of Freire's research on education around the globe. This book covers discussions on:

- The background to and impact of Freire's work

- Alternative approaches to supporting child development

- Pedagogical approaches in Portugal, South Africa, Japan, New Zealand and the United States

Vandenbroeck concludes with a vision for theorising and implementing emancipatory practice in early childhood education in contexts of neoliberalism.

An insightful resource for academics and students in the field of Early Childhood Education and Care, Revisiting Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed is a benchmark of the progress made in the field over the last half a century.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

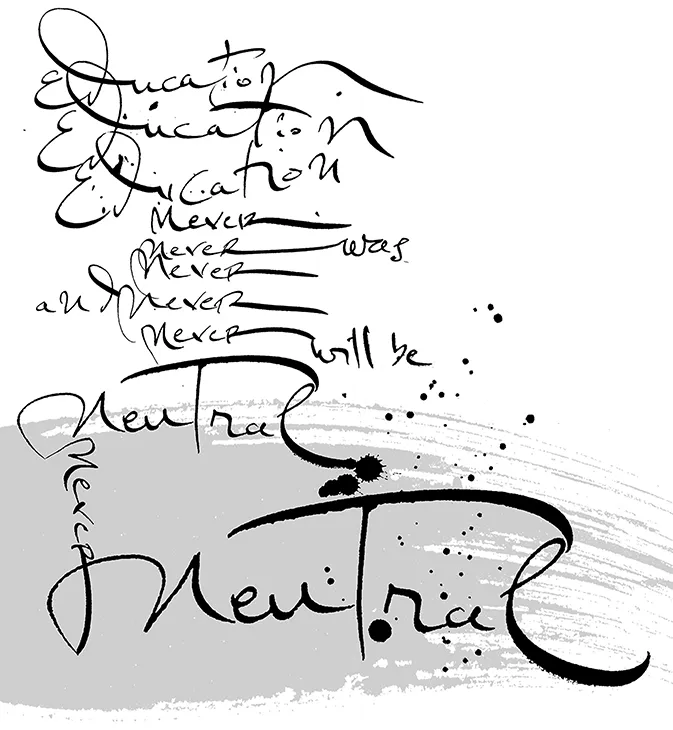

Facts matter. And so do ideologies

Quote from Freire, P., Freire, A. M. A., & de Oliveira, W. (2014). Pedagogy of solidarity.

Walnut Creek CA: Left Coast Press.

Post-foundationalism

Facts matter, but so does ideology

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of contributors

- Introduction: On Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed and this book

- 1. Facts matter. And so do ideologies

- 2. Paulo Freire: His modernity and new ways of thinking about early childhood education

- 3. A Freirian view of early childhood education in Portugal: A complicit response to Michel Vandenbroeck’s Introduction

- 4. Pedagogies of children and youth in South Africa: Why Paulo Freire is crucial in this age of neoliberalism

- 5. Contesting the evidence: Alternate approaches to supporting children’s development through critical consciousness

- 6. Power to the Profession? Reading and repoliticizing early childhood workforce development in the United States

- 7. The praxis of local professional groups exploring alternatives for the banking concept of early childhood education in Japan

- 8. The depoliticisation of professional development in Australian early childhood education

- 9. Transforming early childhood education: Dreams and hope in Aotearoa New Zealand

- 10. Discussion: Early childhood education as a locus of hope

- Index