- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

No Charity There, now in a revised edition, provides the first general history of social welfare in Australia. It traces the development of official and community attitudes to demands and expectations.Using material not previously readily available, Brian Dickey analyses how Australian society has sought to solve the problems raised by a wide variety of vulnerable groups since 1788: the aged, orphans, single mothers, the insane, alcoholics and the unemployed. No Charity There is a carefully researched and intelligent study of a subject of ever-increasing importance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No Charity There by Brian Dickey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Éducation & Enseignement des sciences sociales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Convict Era 1788–1850

The colony of New South Wales began as an open gaol designed to relieve administrative problems of an anxious British government. Lest they die or riot in England, some 700 male and female convicts were shipped to the Antipodes during 1787, together with 400 administrators, guards and associates. Captain Arthur Phillip was appointed Governor and Captain General of this gaol colony. By its nature, and deriving from the ordered society of eighteenth-century England, the settlement at Port Jackson was hierarchic, enclosed, and governed by explicit authority backed by force.

Moreover, it was a colony about whose prospective needs the administrators in England had given little hard thought. Because Phillip was responsible for the total welfare of everyone under his command—from food to pay to shelter to employment to discipline— he soon found himself writing to London about the inadequacies of his resources and instructions. Gaols did not spring ready-made from amidst the rocks and trees of Port Jackson. He and his subordinates needed clothes for the women and children, tools with which to build and farm, drugs to assist health, skilled tradesmen.. .the lists were seemingly endless. Phillip and his successors for 30 years at least, and really until transportation ended (1842 in Sydney, 1854 in Van Diemen's Land) were exercising total responsibility for the people in their charge under orders received from London.

The sick

The First Fleet had scarcely dropped anchor in Sydney Cove before action was required to care for some people who could not care for themselves. Surgeon John White was the first head of the colonial medical service. He and three colleagues had been recognised as a necessary part of the new colony from the planning stages in England. White, Denis Considen, Thomas Arndell and William Balmain arrived with commissions as surgeons to the settlement. They were to be assisted for a while by Thomas Jamison, Surgeon's Mate from the Sirius, and John Irving, an emancipist who had also probably assisted the surgeon aboard the Sirius. As early as 29 January 1788 a series of tents were erected on the west side of Sydney Cove, where the sick, convicts and troops both, were cared for. Some months later a timber building accommodating 60—80 patients was built close to what is now the corner of Argyle Cut and North George Street. The nursing staff was drawn from such convicts as could be spared from more urgent tasks. On 30 June 1788 there were 6 marine and 24 convict patients in the hospital, while another 12 marines and 42 convicts were returned on the parade state as sick in camp. In those first five months 41 people died and 52 convicts had been classified by the surgeons as permanently unfit for work.

The local administration provided this medical service as a necessary part of the gaol it was conducting. The surgeons, the medicine, the buildings all derived from the same British resources as the military and civil organisation, and for the same reason: it was part of the package. Thus, for example, during Captain Hunter's regime the general hospital was relocated farther down the ridge on the north side of the Cove towards Dawes Point; while Governor Macquarie in 1811 arranged a much more dramatic extension of hospital facilities in the building of the new general hospital in Macquarie Street. So pressed was he for funds that Macquarie granted D'Arcy Wentworth and his associates a monopoly of the import of spirits from India—hence the 'Rum Hospital'—as part payment for the contract. That large and pleasantly faced trio of buildings was to survive a multitude of renovations and uses, so that even today the northern and southern wings remain, while a hospital still stands on the central site, between the Legislative Council and the 'Mint Building', now a museum.

At the government-controlled and supported general hospital at Dawes Point and later in Macquarie Street, not only those for whom the government admitted direct responsibility but all who needed it received medical attention. Only the troops were treated separately. The army system provided them with doctors, and a hospital was built in their Sydney barracks complex and also at one or two other stations (notably the gracious Greenway building at Liverpool, which is now part of the local technical college). Need was defined financially as well as medically. Assigned convicts and poor free settlers came to the general hospital, and their employers were expected to reimburse the government. Alternatively, two reputable persons might guarantee the costs, fixed by the 1830s at Is per day and then Is 9d by 1840. The guarantors had also 'in the event of his death to defray the expenses of his interment1. As often as not, however, the colonial government had to find the charge for these pauper patients. Others, of course, found no need for such hospitalisation, for the surgeons gained the right of private practice in Sydney at least by 1810, and hence were attending the more well-to-do in their own homes. Thus, after so few years, medical care in the colony took on its long lived ambiguity. Those who could arrange matters directly did so, proving both their suspicion of early nineteenth-century hospitals, and their clear class perception that hospitals were for the poor, not for the ruling classes. The Reverend Mr Cowper called the General Hospital the 'Sydney Slaughter House1, while someone labelled the one at Parramatta 'an infamous brothel'. ' The gradual erosion of that judgement about the social function of hospitals was to be a principal theme of their history in Australia over the next 150 years. The competing interpretations of that function, one based on medical need, and the other on financial, even social distinction, were to press against one another repeatedly.

2 The General Hospital, Macquarie Street, Sydney.

The government also had to provide health care in the outstations of the convict establishment of New South Wales. As centres of convict administration were established, so institutional medical facilities to support the convicts (and usually also the soldiers) were provided: at Parramatta, alongside the gaol and the barracks; at Liverpool, Windsor, and later, at Goulburn, Bathurst and Moreton Bay. There were other, more temporary, facilities too: typically little more than additions to the local gaol in the lesser centres of settlement. In general, the services the government provided coped principally with accident cases, and perhaps with chronic cases till they died. If concurrent English practice—and the subsequent colonial rule—is any guide, every effort would have been made to exclude infectious cases. Nonetheless, it was acknowledged that there was a general necessity to provide care for these people, and it was provided, however superficially by late twentieth-century standards. Again, as in England, these facilities were better than nothing. Poor people preferred to use them, rather than go without altogether: they voted with their feet, perhaps the best evidence available of the usefulness of these places.

In Van Diemen's Land, likewise, facilities began in improvised ways, in rented houses and wooden huts, and with a string of incompetent medical officers.2 The Hobart Hospital when Bigge visited the town was a house accommodating 20—30 people, and servicing 10—20 out-patients daily. It was the third or fourth generation facility in Hobart, the equivalent (in sequence at least) of the Macquarie Street building in Sydney.3 There were hospitals of a sort also at Launceston and George Town, as well as a hired room for the chronically ill in Hobart. During Governor Arthur's long regime extensions were made to the Hobart facilities, though, as always, they were never adequate. Because of the longer convict period in Van Diemen's Land, the facilities there were still government provided and controlled into the 1850s. There were several other hospital facilities in the country districts of Van Diemen's Land, but like those in New South Wales, they were nothing more than rooms attached to the local gaols. All, even in the 1840s, were criticised for their inadequacy by even the most austere standards. At least at New Norfolk, a major centre of convict administration, there was a substantial hospital facility by the 1840s, but its role was principally as an invalid depot. This was because of the long continued flow of convicts from Britain, and also because of their declining quality, both as they aged in custody and in the types selected in the last hectic decade of transportation.

After continuing criticism of the existing buildings the administration agreed (in 1842-43) to build a new hospital in Hobart to house 150 patients. This met the needs of the southern half of the colony for the remainder of the convict era. It was in due course to attract the angry attention of a new, self-confident generation in the 1860s who were to demand something 'better'. In Launceston nothing new was built, and as the convict regime ran down in the early 1850s efforts were made by the government to close the hospital there. It increasingly accepted destitute free patients as well as convicts and, as a result, the financial burden was transferred from British to colonial government hands. The continuity of social concept was thereby maintained; it was a facility for the sick poor of the colony.

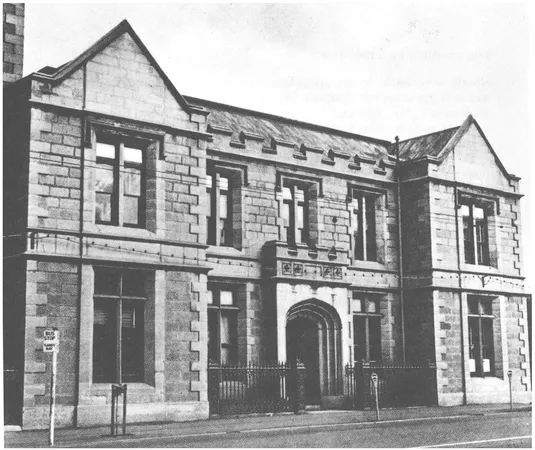

Dr E.S.P. Bedford, an active medical practitioner in Hobart, was responsible for an interesting alternative to the usual pattern of health care. He established a small private hospital in 1840 called St Mary's, funded both from charitable donations and—here was the innovation—the weekly subscriptions of working-class potential users. He argued that no hospital existed for non-convict sufferers, and that such people did not care to be treated alongside convicts. The contributory principle seems to have had little appeal in Hobart (or in Launceston, where a similar attempt was short-lived), and St Mary's closed in 1860.

The associated medical problem of the care of lunatics (the term then used for mentally ill people) also began to force itself on the administrators of the convict colonies. Care for the mentally ill had a low priority; legislators and doctors had little clear theory to work on; the community feared the sufferers. At first such people were only one part of a general collection of incompetents whom the colonists grudgingly acknowledged. As their numbers grew specific custodial action was required. In New South Wales lunatics in the early years were confined in the town gaol at Parramatta where conditions were harsh and unrelenting. Governor Macquarie decided an asylum should be erected for them, and in 1811 buildings were provided not far away from Parramatta at Castle Hill.4 The early instructions to the superintendent emphasised cleanliness, the proper issue of food, the absence of undue force and fraud, the need for occupational therapy, and for regular reports. It was an example of good intentions which would be overwhelmed by growing numbers, increasingly inadequate facilities, a niggardly financial provision, medical ignorance and incompetent staff.

In 1838 a purpose-built institution for lunatics was opened at Tarban Creek on the Parramatta River, where it remains to this day. It received both non-convict and convict patients: as convict numbers declined from a peak after the Napoleonic wars of 45.4 per cent of the population of New South Wales, to 29.6 per cent in 1840, so the number of non-convict patients rose in the asylum. There was never any debate about the impropriety of this trend. A similar facility was tacked on to the New Norfolk establishment in Van Diemen's Land in 1833 to accommodate 40 patients. Typically, it was soon overflowing.

3 St Mary's Hospital, Hobart. Photo taken in the 1960s.

As the 1840s wore on, the withdrawal of the British government from the support of the two colonies inevitably meant that, short of emptying the asylums and tipping the patients out on to a terrified community, the local administration had to fund and run these custodial institutions. Admission procedures were often informal. It was not till the period of full local legislative responsibility after 1856 that the English obsession with the legal problems of improper incarceration found expression in local law. Lunacy, in so far as it generated any public debate at all, tended for a long time to be a legal issue. There were also a few attempts to set up private asylums, but they were often criticised for profiteering. For the rest, governments were left to provide the necessary custodial facilities. And so they did: the social service was always there, if only in the most scanty form.

Lunatics were regarded as a threat to the community. Walls had to be built to keep them in, and prevent disturbance to suburban rectitude. Action was usually taken with little thought for the inmates. Complex political manoeuvre and personal ambition were sometimes more important than any genuine understanding of the medical issues involved. Consider for example, the first ten years of the existence of the colony of South Australia. At first, destitute lunatics were housed in the two ramshackle huts which served as infirmary and gaol. In 1841 the government contracted with Dr J.P. Litchfield to care for the insane. But he was rejected as merely a disappointed office-seeker looking for a steady income. So the patients were shuttled between the destitute encampment, the hospital and the gaol. Efforts to legislate for legal constraints on lunatics were short-sighted and inaccurate, partly because the South Australian law-makers saw them as public nuisances. The lunatics went to the gaol, where any cures were fortuitous and treatment could lead to death. In 1846 a specific asylum was opened, with five cramped rooms for the patients, no facility for the separate care of violent patients and an air of total inadequacy. The surgeon was uninterested in the care of the insane, who were in effect left to the head keeper, William Morris, who might have tried according to his lights, 'but who was "no very proper person to superintend the care of lunatics as respects their safe keeping"'.5 By the 1870s, however, a substantial asylum had been erected, controlled by conscientious and thoughtful medical superintendents. They still had to grapple with rising numbers and limited resources.

One figure to emerge with integrity is F.N. Manning, superintendent at Tarban Creek (NSW) from 1868 to 1876, and then Inspector General of the Insane in New South Wales from 1879 to 1898. He transformed the Tarban Creek Asylum at Gladesville from a "cemetery for diseased intellects' to a hospital where cures were effected. A separate asylum for imbeciles was established in 1869 in Newcastle. As Inspector General he produced a series of reforms to correct the accumulated evils of the old Parramatta Asylum, and then proceeded to draft the powerful NSW Lunacy Act (1878) which gave legislative backing to what he had long sought: procedures for admission and discharge, definition of the responsibilities of doctors, centralised control and supervision of the asylums. He encouraged visitors and public debate about insanity to break down ignorance and prejudice. He pressed for new facilities to reduce overcrowding and improve treatment, gaining new institutions at Callan Park and Kenmore (near Goulburn), as well as an admission facility near the Darlinghurst Gaol. He sought to pay his attendants decent wages and constantly sought to have lunacy treated as a serious and proper subject of medical action.6

Later in the nineteenth century it was not difficult to justify the spending of funds on country institutions, far from the gaze of respectable people. Asylums were set up near Goulburn in New South Wales, at Ballarat in Victoria, or on some obscure island in Moreton Bay in Queensland. Well into the twentieth century this form of medical facility attracted little or no attention except at times of energetic investigative journalism. Custody, restraint, occupational therapy, increasing efforts at classification and successive generations of massive building all took their place in this difficult and frustrating field of medical care.

Care for those mentally ill was a government health service, readily available to the whole community, though sometimes for a fee. So obvious was the justification for arguing that insanity was outside the responsibility of the person affected that its care never attracted the controversy over access and financial responsibility which, for example, ordinary hospitals in the late nineteenth century or unemployment relief in the 1930s or the 1970s generated. To all but the socialist, mental hospitals were a minimal, cost-consuming facility unfortunately necessary as much for the good of society as for the relief of the sufferer. To the socialist these hospitals might be a model of the ultimate entitlement of all the community to medical welfare when needed.

Children

Care for children began with the instructions Phillip received from the British government. He was to provide for the financial security of Anglican clergy and for a schoolmaster by reserving land for them. It was not long before natural increase and the steady accumulation of child prisoners forced action. The chaplain employed a group of schoolmasters for a while, though with little success. Instruction for children of the well-to-do, in the colony as in England, was a matter of private action. The government had to provide minimum instruction, and even custody, for the children of the lower classes, for whom fees were out of the question, and whose destiny was clearly to be members of the working classes. Various expedients were adopted to find schoolmasters, notably from among educated convicts. By 1806 there were eight in government employ, though the deposition of Bligh in 1808 a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Prefaces

- Introduction

- 1 The Convict Era 1788-1850

- 2 Charity in the Age of Free Trade 1835-70

- 3 Review and Expansion 1870-90

- 4 Charity or Universal Entitlement? 1890-1916

- 5 Charity in Crisis 1916—41

- 6 Social Welfare under a Federal Labor Government 1941-49

- 7 Social Security for the Middle Classes 1949—72

- 8 Welfare as Justice? 1972-86

- Notes

- Index