CHAPTER 8

Methodological Issues

As in most domains of psychological inquiry, research on semantic priming has advanced on two fronts. One line of research has focused on understanding the phenomenon itself; the other has focused on how best to measure the phenomenon. In this chapter, I review research of the second type and examine several important methodological issues that should be considered when designing semantic priming experiments. Although one might expect to find discussions of prime-target SOA, the relatedness proportion, and the nonword ratio in this chapter, I have postponed discussion of these variables until Chapter 9 because they are crucially involved in the theoretical distinction between automatic and strategic priming.

□ Counterbalancing of Materials

The measurement of semantic priming requires that performance in two experimental conditions be compared. Typically, performance on words preceded by semantically related primes (e.g., lion-tiger) is compared to performance on words preceded by semantically unrelated primes (e.g., table-tiger). Sound experimental design dictates that these experimental conditions should differ in as few ways as possible other than the semantic relations between the primes and the targets. In the context of a semantic priming experiment, this means that the same items (words, pictures, etc.) should be used in the semantically related condition and in the semantically unrelated condition. In principle, this goal should be easy to achieve: use the same items in the related and the unrelated conditions for each subject. This solution is not attractive because stimulus repetition may interact with semantic relatedness in unpredictable ways. Although the results of studies that have jointly manipulated semantic relatedness and target repetition indicate that these variables have additive effects (den Heyer, Goring, & Dan-nenbring, 1985; Durgunoglu, 1988; Wilding, 1986), those studies have not presented items more than three times. An interaction between semantic relatedness and repetition might occur if decisions on repeated items were made using episodic memory rather than semantic memory. If the response to a stimulus is made on the basis of memories of previous responses to the same stimulus, semantic priming may be weak or non-existent. Target repetition becomes even less attractive as the number of experimental conditions, and hence possible repetitions, increases.

The standard solution to the materials confound is to counterbalance stimuli through experimental conditions across subjects. Consider the simplest case in which related prime and unrelated prime conditions are compared. A given target would appear in the related prime condition for one subject (e.g., fail-pass) and in the unrelated prime condition for another subject (e.g., vacation-pass); similarly, a second target would appear in the related prime condition for the second subject (e.g., day-night) and in the unrelated prime condition for the first subject (e.g., sell-night). In this manner, each subject sees each target once, but across subjects, each target appears in each condition.

The same counterbalancing manipulation should be performed for primes so that they, too, are not confounded with experimental conditions. To this end, the set of related prime-target pairs can be randomly divided into two subsets of equal size (A and B). Two subsets of unrelated prime-target pairs (A′ and B′) are generated by re-pairing primes and targets within each subset of related pairs. The related and unrelated pairs for one test list are selected by choosing a subset of related pairs and a subset of unrelated pairs, such that no prime or target is repeated (e.g., A–B′). A second test list is created by making the complementary choices (e.g., B–A′). Half of the subjects will see the materials in one test list and half will see the materials in the other test list. An example can be found in Table 8.1.

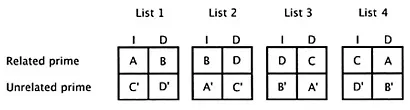

This approach generalizes to any number of experimental conditions. Suppose, for example, that an investigator wanted to investigate semantic priming for intact and perceptually degraded words. The design would have four experimental conditions: Related versus Unrelated X

TABLE 8.1. Example of counterbalancing targets and primes through related and unrelated prime conditions.

Intact versus Degraded. The set of related prime-target pairs would be divided randomly into four subsets, and each subset would be used to generate a subset of unrelated prime-target pairs. Four test lists would then be created by assigning subsets of prime-target pairs to the four experimental conditions such that each target item would appear in each of the four conditions across lists but no item would be repeated within a list (see Figure 8.1). One fourth of the subjects would see each test list. Other designs can also be used (e.g., Pollatsek & Well, 1995).

In general, for p experimental conditions, at least p test lists are needed, and each test list is seen by N/p subjects. If the experimenter wants to collect n observations per condition per subject, then np unique, semantically related prime-target pairs are needed. The advantage of this type of design is that the manipulation of semantic relatedness is not confounded with irrelevant differences in materials. This feature is especially crucial when one has a priori reasons to believe that priming may be small (e.g., subliminal priming; see Chapter 14) or uses a dependent measure that is known to be highly sensitive to structural properties of stimuli (e.g., ERPs; see Chapter 18).

Designing an experiment to meet this high standard is tiresome, especially when the experiment contains a large number of experimental conditions. It is therefore tempting to use different stimuli in the experimental conditions and to try to equate the stimuli in the various conditions on features known to affect decision performance, such as word frequency, word length, and part of speech. The fundamental problem with this approach is that stimuli are equated only on those variables that the experimenter happens to think of. Effects due to differences between items are inextricably confounded with effects due to the experimental manipulation of semantic relatedness. Another tempting strategy is to assign materials to the related and the unrelated prime conditions randomly. This approach is probably acceptable if each subject-condition combination receives a unique sample of stimuli. The problem with such a design is that it may require an enormous number of stimuli. In many studies, materials are a precious resource because they are difficult to construct, because they must satisfy many constraints created by the experimental conditions or because subjects have limited time in the experiment. More commonly, the same random assignment of stimuli to experimental conditions is used for all subjects. This approach may be acceptable if large numbers of stimuli and subjects are used. In general, a counterbalanced design is the design of choice in investigations of semantic priming.

FIGURE 8.1. Example of counterbalancing materials through four experimental conditions formed by the factorial combination of semantic related-ness (related prime versus unrelated prime) and stimulus quality (intact versus degraded targets). A, B, C, and D are equal-sized subsets of related prime-target pairs. A′, B′, C′, and D′ are corresponding subsets of unrelated prime-target pairs formed by re-pairing related primes and targets. I=intact; D=degraded.

Of course, if the materials themselves constitute a factor in the design (e.g., semantic priming for nouns vs. verbs), then stimuli cannot be counterbalanced across conditions defined by that factor. However, even in this case, one can counterbalance targets and primes across the semantic relatedness manipulation and guarantee that semantic priming within a type of material is not confounded with differences between items. When type of materials is a factor in the design, utmost care should be taken to match the stimuli in the various materials conditions on those variables known to affect semantic priming. Such variables include associative strength (e.g., Canas, 1990), semantic relatedness (e.g., McRae & Boisvert, 1998), type of semantic relation (e.g., Moss, Ostrin, Tyler, & Marslen-Wil-son, 1995), and word frequency (e.g., Becker, 1979). Recent experiments have shown that naming and lexical decision responses are faster for words that do not have a common synonym than for words that do (e.g., milk vs. jail, Pecher, 2001) and that item recognition and cued-recall performance are influenced by several features of prior knowledge, including the number of connections among the associates of a target word (e.g., Nelson, McEvoy, & Pointer, 2003; Nelson & Zhang, 2000; Nelson, Zhang, & McKinney, 2001). To my knowledge, it is unknown whether or not these variables influence semantic priming, but prudence would call for controlling these variables, as well, in experiments in which stimulus type was a factor.

Because of missing data (e.g., errors, apparatus failures), the statistical analysis of the results of a semantic priming experiment is typically based on summary statistics, such as the mean or the median, computed for each subject and each experimental condition. The analysis of such data obtained from a counterbalanced design should include counter-balancing list as a grouping variable. That is, subjects who see the same counterbalancing list are treated as a level of a grouping variable in a mixed-model analysis of variance. I refer the reader to the excellent articles by Pollatsek and Well (1995) and Raaijmakers (Raaijmakers, 2003; Raaijmakers, Schrijnemakers, & Gremmen, 1999) for thorough discussions of this topic. Although the analyses recommended by these authors differ in certain details, they share the goal of isolating variance introduced by having different subjects respond to the same items in different conditions.1 Moreover, as discussed subsequently, these analyses eliminate the need for conducting a separate analysis over items. To reduce test list X experimental condition interactions, target stimuli can be matched across lists on item characteristics (e.g., word frequency, word length) or on normative data (e.g., mean decision latency in neutral or unrelated prime conditions).

□ Subject Versus Item Analyses and Fixed Versus Random Effects

The data obtained in a counterbalanced design can be analyzed with subjects or items as the unit of analysis. In the subject analysis, data within each cell are collapsed over items using the mean, median, or some other measure of central tendency; in the item analysis, data are collapsed over subjects. The F ratios from these analyses are typically identified as F1 and F2, respectively. It has become common practice since the publication of Clark’s (1973) influential article to report both analyses and to reject the null hypothesis if both analyses reveal statistically significant F values. There is widespread belief that F1 assesses the extent to which the treatment effect generalizes over subjects and that F2 assesses the extent to which the treatment effect generalizes over items.

In fact, these beliefs are incorrect (Raaijmakers, 2003; Raaijmakers, Schrijnemakers, & Gremmen, 1999). The F ratio for a treatment effect tests whether the condition means are equal in the population, taking into account an appropriate measure of variability. It does not test the extent to which the treatment effect is similar across subjects, in the case of F1, or items, in the case of F2. An F ratio can be statistically significant even when a small proportion of subjects or items shows the effect (see Raaijmakers, 2003, for examples). This feature of F tests is not a problem or limitation; it is an essential consequence of what the analysis of variance is designed to accomplish.

F1 and F2 were introduced by Clark (1973) as a means of computing minF′. This statistic is an approximation of the quasi-F ratio that can be used to correct for the bias introduced into F1 in many experimental designs when stimuli are treated as a random effect (Winer, 1971). However, minF′ is not needed in designs in which stimuli are matched on various characteristics across experimental conditions or in counterbalanced designs, regardless of whether stimuli are treated as fixed or as random (Raaij-makers, 2003; Raaijmakers, Schrijnemakers, & Gremmen, 1999). In the case of the matched design, bias in F1 is greatly reduced by matching of items and the use of minF leads to a substantial reduction in power (Wickens & Keppel, 1983). If counterbalanced designs are analyzed properly (as described previously), then correct error terms can be found for all treatment effects and quasi-F ratios are not needed, even when stimuli are a random effect (Pollatsek & Well, 1995; Raaijmakers, 2003; Raaijmakers, Schrijnemakers, & Gremmen, 1999). Joint reporting of F1 and F2 is never correct; one should report either F1 or the appropriate quasi-F ratio (or its approximation, minF′). Because that statement contradicts an entrenched practice in the field, I repeat it, in its own paragraph, to ensure that there is no misunderstanding:

Joint reporting of F1 and F2 is never correct; one should report either F1 or the appropriate quasi-F ratio (or its approximation, minF′).

Although the analysis of matched and counterbalanced designs is not influenced by whether stimuli are a fixed or a random effect, the analysis of many other designs is affected by the status of the stimuli (e.g., a design in which the same random assignment of stimuli to experimental conditions is used for all subjects). How does one decide whether stimuli are fixed or random? The answer to this question is not as simple as one might like.

Several criteria distinguish fixed and random effects in experimental design (e.g., Kirk, 1995). In this context, “effect” refers to a variable or factor in the design (e.g., subjects, stimuli, experimental conditions). Fixed effects have the following three properties:

- A fixed effect includes all of the levels of interest. For example, if an experimenter wanted to know whether priming was affected by associative relations between primes and targets, he or she might include prime-target pairs that were semantically related and associatively related (e.g., cat-dog), semantically related but not associatively related (e.g., goat-dog), and unrelated on both measures (e.g., table-dog; see Chapter 10).

- A replication of the experiment would include the same levels. Hence, a replication of the just-described semantic priming experiment would include—at the bare minimum—the same three prime conditions.

- Conclusions drawn from the experiment only apply to the levels of the effect that were included. Returning to the example, the design would justify conclusions about the associative and the semantic relations manipulated in the experiment but not about other kinds of prime-target relations (e.g., syntactic relations).

Random effects are the complement of fixed effects: The levels included in the experiment are a random sample from a larger population of possible levels. A replication of the experiment would include a new random sample of levels, not the same levels. Because the levels included in the experiment are a random sample from a larger population, the experimenter can generalize conclusions to the population from which the sample was drawn.

Most treatment effects in psychology are fixed effects. It is indeed rare that experimental conditions are randomly selected from a population of possible conditions. The effect of subjects, however, is usually considered a random effect. In a good experiment, subjects are randomly selected from a well-defined population, and a replication of the experiment would include a new random sample of subjects, not the same subjects. It is important to appreciate that the word “random” is not used idly in the definition of a random effect. The fixed or random status of an effect is determined by how levels of the variable were selected, not by the wishes of the experimenter (Cohen, 1976; Smith, 1976). An experimenter may want an effect to be random, but unless levels have been randomly selected, it is not random. Cohen’s (1976) title is apt: Random means random.

In my experience as a producer and consumer of semantic priming experiments, the materials are never randomly selected—or even pseu-dorandomly selected—from a population of possible items; in fact, they are usually selected or constructed to meet peculiar demands of the experiment or to maximize the strength of the experimental manipulation. Thus, although an experimenter may wish that his or her materials could be treated as a random effect, they almost always will be a fixed effect.

A natural response to this statement might be to say that the same is probably true of subjects: subjects aren’t randomly selected, so the same problem exists there too. Perhaps, but even if this is true, the fact that an approach is bad in two cases does not somehow make it right for both. Selection of subjects in a well-designed experiment can be random, and it often approximates random selection from a well-defined population, usually introductory psychology students. People can argue about whether that population is a reasonable one, but for most of us in cognitive psychology who make our livings worrying about how undergraduates think, it is probably as good as any. Moreover, there is no reason to believe that subjects are selected (or select themselves, in situations in which subjects sign up for experiments) in a way that relates to the independent variables. In contrast, as was noted earlier, items are typically selected in such a way as to maximize the effects of the independent variable. In sum, one can quibble about whether...