Learning is central to human life—as essential as work or friendship. As the American experiential learning theorist David Kolb (1984) has noted, learning is human beings’ primary mode of adaptation: if we don’t learn we may not survive, and we certainly won’t prosper. Learning is complex and multifaceted, and should not be equated with formal education.

All human activity has a learning dimension. People learn, continually, informally and formally, in many different settings: in workplaces, in families, through leisure activities, through community activities, and in political action. There are at least four forms of adult learning.

Incidental learning

This type of learning occurs while people perform other activities. So, for example, an experienced mechanic has learned a lot about cars, and elderly gardeners carry a great deal of knowledge of their craft. Such learning is incidental to the activity in which the person is involved, and is often tacit and not seen as learning—at least not at the time of its occurrence.

As people live and work they continually learn. As Stephen Brookfield (1986:150) has noted, most adult learning is not acquired in formal courses but is gained through experience or through participation in an aspect of social life such as work, community action or family activities. Until recently, writers on adult education paid little attention to informal and incidental learning (see Marsick & Watkins 1991; Foley 1999). We are just beginning to study and act on these forms of learning. In what follows, I outline some of the directions we might take.

Learning is often unplanned, is often tacit, and may be constructive or destructive. The content of learning may be technical (about how to do a particular task); or it may be social, cultural and political (about how people relate to each other in a particular situation, about what their actual core values are, or about who has power and how they use it).

If there is learning there is also non-learning. People often fail to learn, or actively resist learning. Consider smokers, who persist with the habit in the face of overwhelming evidence of its harmfulness. Or countries, like Australia, that continue to clear marginal arid land for farming despite the knowledge that this is economically unviable and ecologically destructive. Or a university department that attributes falling enrolments to a shrinking pool of clients in the face of clear evidence of student dissatisfaction with the quality of teaching. (For an extended discussion of failure to learn, see Foley 2001: ch 5.)

If there is education there is also miseducation. Educators like to distinguish between propaganda and education, seeing the one as closed, manipulative and oppressive, and the other as open, democratic and emancipatory. While this distinction has its uses, adult educators also need to become aware of propaganda as a powerful and commonly used form of distorted and distorting education. Propaganda works on simplification: it appeals to fear, hatred, anger and envy. The resources available for corporate and government propaganda, and the scale of it, often make the efforts of adult educators appear puny.

Most learning episodes combine learning and non-learning, education and miseducation. The history of HIV-AIDS education illustrates this complexity.

When it emerged, HIV-AIDS was considered to be a short-term problem, largely confined to the gay community. Workers in the field assumed that medical treatment and education would quickly bring the virus under control. Early education programs were aimed at mass audiences and aimed to motivate individuals to change their behaviour. These programs often sought change by focusing on the negative consequences of practices such as unprotected anal intercourse or the sharing of intravenous needles. This ‘social marketing’approach to HIV education, which has also been applied to issues such as road safety and reducing cigarette smoking, assumes that if sound information is transmitted to the ‘target’ audience in a convincing way then ‘customers’or ‘consumers’will behave in the way desired by the originator of the message (Foley 1997).

After initial apparent success in western countries in the 1980s it became clear that social marketing education was not reducing risk-taking behaviour. Reviewing their experience, workers and researchers generated a list of reasons why:

- HIV education often concentrated on providing information and neglected behaviour and the social environment that shapes it.

- Many HIV education programs relied on one-way communication.

- HIV education often treated the virus as a single issue, rather than as part of a wider set of problems including poverty, lack of political power and discrimination.

- Few HIV-AIDS services integrated education and treatment.

- Few HIV education programs tackled the distrust that many people feel towards government and science.

- Programs tended to focus on individual behaviour and to neglect the social and political factors that shaped that behaviour.

This last factor points to the basic problem with social marketing education: it simplifies a complex social process. As one HIV researcher put it,‘sexuality and drug use are complicated behaviours, deeply rooted in cultural, social, economic and political ground’ (Freudenberg 1990, p. 591). Another HIV activist/researcher, Bruce Parnell (1996 a & b), articulated the problem more arrestingly. We must, he said, acknowledge the tension in all gay men, between their rational understanding that unprotected anal sex can lead to HIV transmission, and their desire for this ‘warm, moist and intensely human’ experience. Educational programs that simply focus on the mechanics of safe sex, whether it be condoms themselves or negotiating their use, suppress this tension. The result is that the tension is buried, and men practice unsafe sex anyway, some frequently, others less frequently, but all of them, probably, sometime.

Only by reversing this suppressed tension, Parnell argued, by surfacing and discussing the conflict between reason and desire in gay men, could real education take place. To achieve this, HIV educators need to use dialogue, not teaching. Educators should see themselves not as experts bringing answers but as a partner who seeks to act as a catalyst, prompting and facilitating discussions which will enable gay men to explore their own experiences, learn from them and make more informed choices.

In taking this position, Parnell and other HIV educators aligned themselves, often unknowingly, with adult education forms and traditions that contributors to this book discuss at length. But for too long, too many practitioners and scholars have failed to grasp the complex, contextual and often contested nature of adult education and learning. As a professional field, adult education and training has concentrated on developing practitioners’ core skills (teaching/group facilitation, program development) and their knowledge of the psychology of adult learners. As the field has developed, specialist knowledge-bases have emerged:vocational education, human resource development, distance education, radical and popular education, organisational learning, public education. Some attention has also been paid to the history, philosophy and political economy of adult education, and central issues like research, policy and equity.

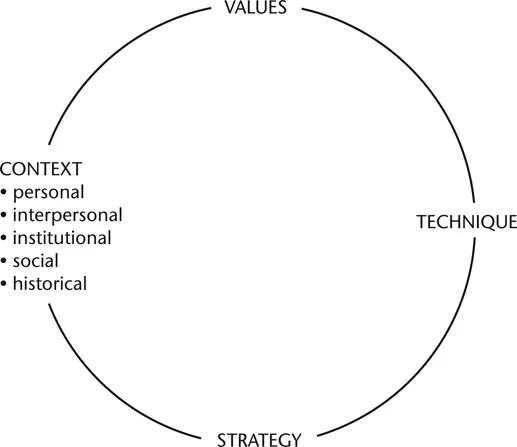

All these issues are important and are discussed in this book. But adult education, as a profession, a field of study and a social movement could contribute much more. The chapters in this book address aspects of this larger contribution. But first I need to say something about the book’s conceptual framework.